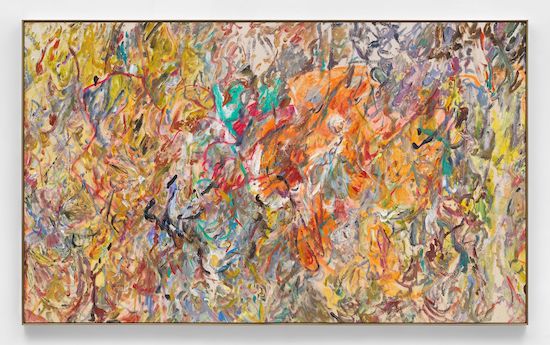

Larry Poons (2019) Warrior River Boy. Acrylic on canvas

170.2 x 281.9 cm

“Painting is a fast medium. You go from here to there with a substance – and you do it quickly.” For Larry Poons everything is fast. Everything is immediate. Everything is now. So much so that talking about how you actually get there is liable to make him impatient.

When I ask about the process behind a particular work in his new show, his response is sharp, almost brusque. “What do you want to know?” he says. “Painting involves moving the colour from one place to another. That’s painting, whether you’re Rembrandt or you’re Joe Schmo.”

But how do you start a work like this? “Without sounding like a wise guy, by starting!”

If the above exchange make Poons sound like a character from an American movie in the 1970s, then you’re not far off. Born in Tokyo in 1937, he grew up in Long Island and spent most of his life in New York. He talks as fast – and as relentlessly – as he paints. At times he could almost be mistaken for an avuncular figure in some early Woody Allen film (he comes across far more animated and garrulous today than the almost mystical figure he cuts in the recent Nathaniel Kahn doc, The Price of Everything). Were we not several thousand miles apart, I’d half expect him to press a ten cents piece into my palm. It’s an effect only heightened by his occasional recourse to baseball metaphors.

“Painting is about colour. And colour is nothing but light,” he insists. “Somebody who sees light better than you or me, is Ted Williams.” I must have looked blank because he immediately clarified for me: “the ball player.” Williams, it turns out, played for the Boston Red Sox from 1939 to 1960, a nineteen-time All-Star and two-time recipient of the American League Most Valuable Player Award.

“Why does one person hit the ball so much further and more often than you or me? It’s a question of light and eye-arm coordination. You see, a person like Ted Williams, sees the light – meaning the ball – all it is is light that he’s aiming at – and somehow his eye-arm coordination makes him Ted Williams – or Babe Ruth. Same thing. And the same thing with Pablo Picasso. When he looks at colour, he moves! He doesn’t think about moving. It’s immediate.”

Installation shot. Larry Poons at Almine Rech London, 2021. Courtesy Almine Rech

We’re talking over Zoom a few days after the opening of the show at Almine Rech in Mayfair, a rich and expansive show covering nearly five decades of work, from the sumptuous poured paint pictures of the 1970s up to the vivid colours and wafer-thin brushwork of his most recent work. I say “we”. Larry’s doing most of the talking. I can hardly get a word in edgewise. “Do you thi–?” I just about manage to press into one of the brief gaps in Poons’ peal of speech before he launches into something else.

“I saw a show in Nashville, of Impressionism. Did you ever see that?” he starts, but before I get a chance to demure – “It was a great show. They had all these Salon paintings to begin with, meaning what came before the Impressionists. They were enormous paintings. Really. Fifteen feet tall. And they were all beautifully painted. You wouldn’t even call them ‘slick’. You’d just say, they are well painted. They were so popular at the time that the Impressionists couldn’t even get in the front door. So many of them dealt with no-nos, meaning little girls sitting on old men’s laps in dainty dresses. The crowd loved it, because it sneaked pornography into their lives. They knew this. I came away from that show thinking that there’s one thing that bad art has in common, that it’s always well painted. Because that stuff is well painted. Bad stuff has hope!”

Installation shot. Larry Poons at Almine Rech London, 2021. Courtesy Almine Rech

Over the course of a little over an hour on the call we talk about everything from La Monte Young (“the real deal”) to Norman Rockwell (“not a terrible painter”) to Diego Velázquez (“the Henry Kissinger of his time”) to JS Bach (“how did he write all that fucking music? Tons of it! And so much of it is so great!”). But at a certain point it dawns on me that the one thing we haven’t really talked about is Larry Poons. Every time I succeed in squeezing in a question about his life or his work, he sets off on another great spiel about Beethoven or Mondrian or Isaac Newton and I’m left scrambling to keep up.

Until almost the very end of our conversation.

Somehow we’d got on to talking about TS Eliot. “When TS Eliot was a young lad in Kansas – of all places – where he came from, some English teacher of his was struck by something the child had written. What the child had written was something about a spider impaled by a hatpin. And it caught the attention of the teacher. And from then on, they let the child know this. This kid’s got something!”

Did you ever have an important teacher like that yourself who encouraged you early on?

He pauses for a while. And then, in a voice a little quieter, more subdued than I’d heard him speak up to that point, he says, “I might have. I might have…”

Installation shot. Larry Poons at Almine Rech London, 2021. Courtesy Almine Rech

“When I was in high school, I played guitar and sang. And I didn’t have enough credits to get out of high school. So they came up with art for seniors at Great Neck High School. I enrolled because if I passed that, I’d have enough to graduate. And this teacher used to show slides of stuff to all of us and then put us to work. And the teacher, she’d give assignments, but when I didn’t do them, she never bothered to interrupt me to say you’re not doing the assignment. And so the year went by. And one of my collages during this senior year, she asked if she could have it. And I said, sure. And she took it home.

“And the last day of school she came up to me, and she said, you know, Larry, if you wanted to, you might be able to do something in art.

“And I said, Oh no Miss. I’m going to the New England conservatoire. I’m going to learn how to be a composer.

“But it turns out that she was onto something. Maybe! I hope she was…”

Installation shot. Larry Poons at Almine Rech London, 2021. Courtesy Almine Rech

Larry Poons never made it as a composer (though he did, for a while back in the 60s, play in a band called The Druds with LaMonte Young and Walter DeMaria). But at 32 he was featured in MoMA’s landmark New York Painting and Sculpture, 1940–1970 exhibition, alongside Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, the youngest artist in the show. He was a pioneer in what became known as Colour Field painting, was associated for a while with Op Artists like Vasarely (though he didn’t like the term, and didn’t care much for Vasarely). By the time he was in his forties he was already staking out a whole new direction for his work, constantly innovating and trying new things, impossible to pin down.

“That was the thing that took hold, for me,” he says now. “Because I could do it. It wasn’t like if I sat down at the piano and thought I would write a string quartet. I didn’t have it that way. Painting came, music didn’t. It wasn’t something that I had to learn. It was something that I had to do. It just moved at its own rate, at its own time, with me.”

Larry Poons’ work is at Almine Rech, London, until 31 July