All images: Larry Achiampong, Dividednation (2019), Primary PHOTO: Reece Straw

In what is arguably the artist’s most comprehensive presentation to do date, Larry Achiampong’s Dividednation takes place across both gallery spaces in Nottingham’s Primary. Split across two floors and traversing audiovisual, sculpture, installation and text-based works, this exhibition provides an excellent introduction to the myriad forms and dialogues present in Achiampong’s work.

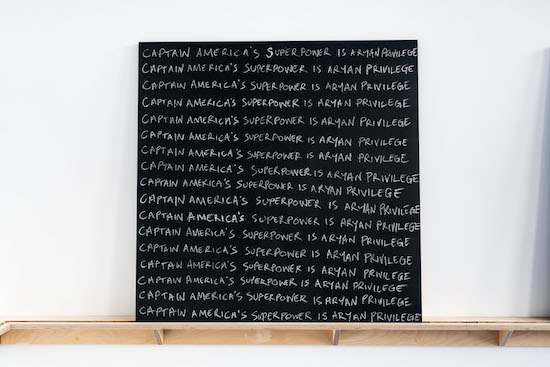

In the ground floor space, there are a selection of the artist’s chalkboards. Large blackboards placed on shelves the length of the gallery’s walls with repeating slogans drawn in chalk. Slogans like “Our lives are political because our bodies are” or “now we’re all trapped inside of a cartoon”.

I find myself asking why someone would think these lines need to be repeated, particularly in a style normally characterising punishment – lines chalked out on a blackboard, again and again. They feel like tweets, captions or memes (the phrases are culled from social media, remixed and repatriated). Little bursts of micro-information with the context supplied only by the experience of the person reading.

I’d be interested to know more about the decision to de/re-contextualise the statements in this way. Written on blackboards in a gallery, separate from their source, the relationship between these texts oscillates from vague to obvious.

As a work carried through Achiampong’s recent career, they make me mostly wonder about their own genesis and less so about the content of the text written on them. The listlessness of the statements on these chalkboards feels reflective of micro-aggressions present in throwaway statements, the repetition as a hard look at the undercurrent of a transient sentence. Capitalising letters, or placing a comma where one may not have been before, re-contextualises the statements in a fashion rendering them pointed, reflecting an alternative underlying communicability. This is most visible in “This Loud, White, Noise”, a board which underscores the intention of these works, a reclaiming of digital micro-aggressions.

A tarpaulin covers the entire gallery floor, comprising part of We Survive And We Prosper (2019), an installation also consisting of a series of laundry bags filled with foil spray painted bronze and gold, stacked in a large pile against the wall of the gallery and taking up significant floorspace. In spite of the chalkboards featuring text, I felt that this work was the one that most directly engaged the viewer on entering the space.

It may seem trite to mention but the decision to use the tarp as a floor covering is an important one. It serves as a delineation of space, indicating that the exhibition-proper begins on entering this room. For me, this was an indication to switch gears as a viewer and to prepare to think consciously about the materials present, actioned by the changing texture underneath my feet.

The installation points to travel, indicators for types of travel and the kind of travel that involves filling every bag that you have available. The laundry bags making up the brunt of the installation are significant, presenting a visual dialogue around the transience of travel, particularly affordable long-distance travel. This isn’t a designer suitcase, or even a holdall, its indicative of temporary but regular states of transience and the necessities present therein.

On the upper floor of the gallery, the three films from Achiampong’s Relic Traveller series play in a darkened space. A viewing chamber is created by the series of Pan African Flag For The Relic Traveller’s Alliance works (Squadron, Community, Ascension and Motion).

Sitting on a bench seat surrounded by the flags as the films play creates an impression of separation. In spite of the influence of Afro-Futurism, it feels like watching history in the future. As convoluted a statement as that may be, the idea around which the series is built (the fall of the West followed by the ascent of the African Union to a state of prosperity, harmony, independence, and responsibility) is something that seemed less prominent to me than the presence of a warning from the future to the ingrained powers in contemporary Western society. Can the West’s many exclusions – through migration, ethnicity, religion or otherwise – only be solved by the fall of the West itself, as Relic Traveller seems to suggest?.

I’ve struggled to write about this exhibition. I enjoyed seeing it, the works included are valuable, interesting pieces which encourage dialogue and are filled with a sense of hope. An anger that motivates change and a desire to force accountability onto oppressors, to fight for a better future. The exhibition is, by any definition, a good one. The reason I’ve struggled to review this show is because I can’t help but feel my privilege in doing so. I can’t help but be reminded of my position in this arrangement, and it’s link to the issues explored by the work here.

As an exhibition, Dividednation makes me painfully aware of my whiteness. Trying to look at it from a neutral perspective, a sort of fantasy of pure criticism in which I attempt to minimise myself as much as possible and see the intention of the work, I’m pulled back to my own position in the economy of privilege. The struggles, the aggressions, the hope – none of this is mine. As an exhibition, this doesn’t feel like it’s trying to draw empathy from the privileged viewer (much the opposite) but that’s where I ended up. I saw the show and felt bad for the oppression, I questioned the extent to which I feel kinship with the notion of whiteness. I don’t feel represented by what that comes to mean, that’s not who I am rings in my head.

This is what I’ve taken away from Dividednation. White privilege is present in the fact that I don’t have to think about my race. I don’t have to represent the white community. I can be an individual without the trappings society implicates my ethnicity in. The way the media represents people of colour, defining communities by race or religion, is racism. It’s an insidious type of racism that promotes segregation and it’s one that can easily go unnoticed, present in everything from job applications to census forms.

Dividednation challenged my perceptions of self. It didn’t give me something easy to write about or a convenient narrative to follow. It confronted me with something that my whiteness gives me the privilege to see when I want to and to ignore when I don’t – that’s something that I believe will stay with me.

Larry Achiampong, Dividednation, is at Primary until 22 June