When Keith Haring arrived in New York in 1978, he was just a twenty year-old kid from Kurtztown, Pennsylvania, an art school dropout who had managed two semesters at the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh before deciding to quit after reading Robert Henri’s book of quasi-philosophical musings The Art Spirit, and an ex-Jesus freak turned wannabe hippie who made his own Grateful Dead t-shirts and hitchhiked across America. “Familiar story,” says director Ben Anthony, whose film about Haring screens on BBC Two tonight. “He was a small town boy who came to New York because he wanted to be somebody different and just completely embraced that, came out and lived a very hedonistic life.”

Thirty years after his untimely death from AIDS-related complications, Haring’s signature style is amongst the most well-known, widespread and easily recognisable in all of contemporary art. The former busboy at the Danceteria could later claim Basquiat, Warhol and Madonna as his personal friends, designed record sleeves for David Bowie, Sylvester and the NYC Peech Boys, and once painted the body of Grace Jones herself for a concert at the Paradise Garage.

Today, Haring’s influence can be seen in the work of artists from KAWS and Shepard Fairey to Banksy and Barry McGee. With a new documentary for the BBC’s Arena strand screening tonight, I spoke to the film’s director Ben Anthony about Haring’s life, work and lasting significance.

How did you first encounter the work of Keith Haring?

I grew up in the 80s as a teenager and he was just somebody whose work was so ubiquitous that I felt a lot of nostalgia attached to it. So the prospect of making a film about him was an opportunity to revisit a lot of the imagery and a lot of the music and a lot of the art and a lot of the culture that I grew up with. It was immediately really appealing. Not only is Keith himself really interesting, but just the period in which he was living and working is so fascinating to me that I really relished the opportunity to dig up film archive and interview some of the people that knew him.

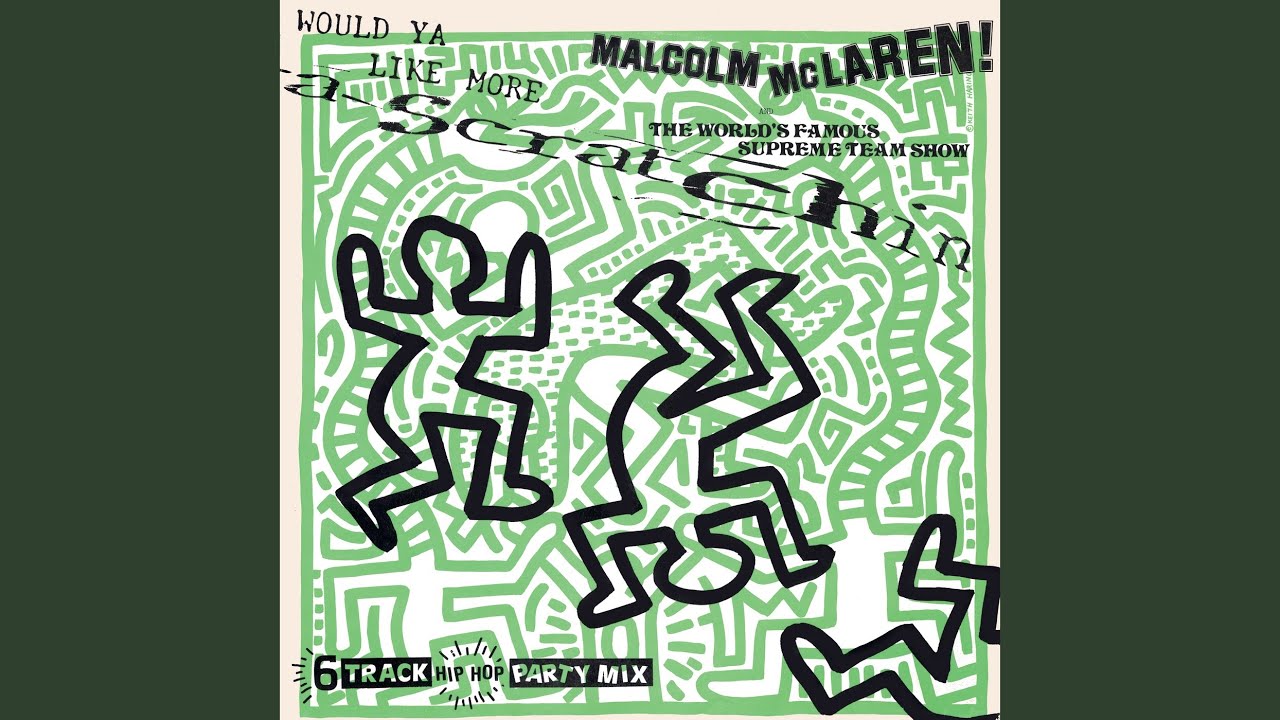

One of the things that really struck me about him is that he seemed really unlikely. He was a sort of skinny, nerdy white guy and he was sort of part of a cultural package that came across from New York in the early 80s that was to do with graffiti art and breakdancing and hip hop and street culture generally. And I was always really fascinated by him because I sort of wondered how this bloke was involved in it. Because he was completely down with that whole scene and was really respected and known by a lot of people, his art tended to accompany a lot of the music.

I’ve got a lot of records that I bought as a kid in the 80s that have his artwork on them. I remember the World Famous Supreme Team, who Malcolm McLaren worked with on Duck Rock, they brought out an EP and it had some Keith Haring artwork on the cover, this iconic sort of dog and dancing man imagery. That was the first time I had any of his work in my house, as it were. It felt like it came with the scene.

What were some of the more surprising things you managed to dig up in the course of making the film?

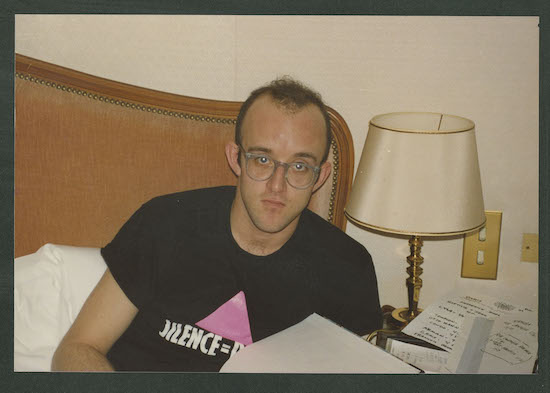

I didn’t know the extent of his hedonism. I didn’t know that he was out cruising every night in bath houses or that he went to nightclubs every night of the week. That was a surprise. I also didn’t know just how many drugs he took. He had an extraordinary appetite for drugs. And the fact that he was still so prolific is amazing. Most people that I’ve encountered who take a lot of drugs can’t really get up the next day whereas he seemed to be able to… well, it sort of fuelled his energy.

He and his friend Drew, who he shared an apartment with, they just took loads of drugs all the time. And actually when you look at a lot of photos of Keith from the time and you know that, you can sort of tell. It’s a funny thing. He’s got a sort of glazed look a lot of the time and I just thought that was his natural, default expression but actually now I know what he was imbibing, it doesn’t surprise me that he looked glazed over. I mean, he would have all night sessions where he would be smoking weed and doing other stuff but also be working all the time, so the next morning he would have produced a whole bunch of stuff and then he would go home and sleep for a few hours and then go back and do more of the same.

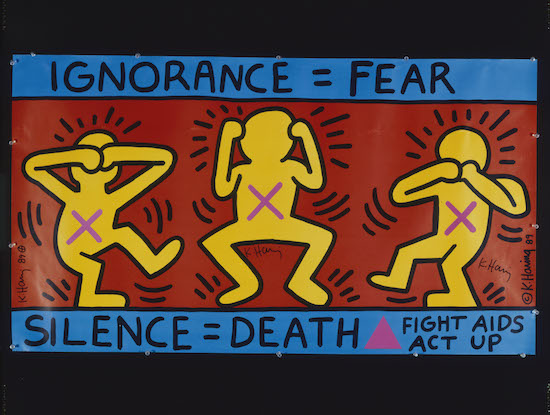

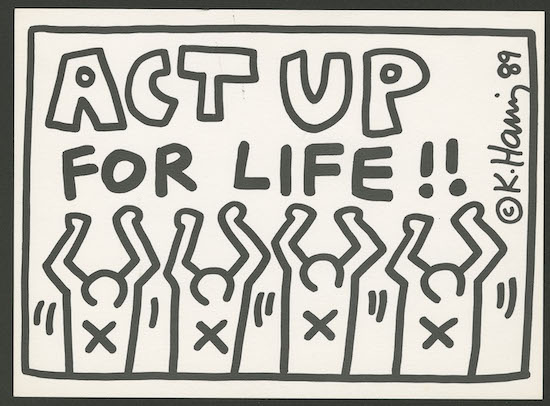

Also, he was just an incredibly generous person. That was something that every single person I spoke to said about him. It was also one of the first things that they said about him, that you’ve got no idea how generous he was. He wasn’t just generous financially – which he was – not just giving money to causes that he believed in, like Act Up. But he was also incredibly generous with his time. He would devote days at a time to community projects for which he’d get nothing back other than the satisfaction of knowing that he creating something.

What is it about his work that appeals to you?

It’s really interesting because when you actually look at how he arrived at his signature style, it went through lots of different iterations. It went through abstract art and semiotics and William Burroughs-style cut-ups, playing with words. And then eventually those words changed into images.

I think that was the thing that was really interesting about him, that he was essentially doing a tag, but it was an image and not a name or a word. What he managed to do, really smartly – and I don’t even know if it was really intentional – was to be part of that tagging culture but without actually writing his name. He was known all over the city – which was what graffiti artists aspired to. He was a bit of a mystery figure. And I think that worked brilliantly for him because people became very familiar with his art before they even knew who was responsible for it.

And just the ubiquitousness of it is a really key part of it. I can’t remember the number but he completed an insane amount of work, if you include all the murals that he did. It’s a sort of mass-production, but an unorthodox version of mass-production. And eventually that did turn into t-shirts and baseball hats and duvet covers and so on. But I think that what he demonstrated was that it was possible to be an outsider and do things your own way but also be omnipresent and have mass appeal. I think that’s quite appealing to the generation of artists that came after that.

Why did you want to make this film at this particular time? What is Haring’s ongoing relevance in the twenty-first century?

The thing about his story that always really fascinates me is the ability for somebody to reinvent themselves. There’s so much mythology about art and artists, that they are just natural born geniuses. And I think when you look at his early work, you realise that he wasn’t really exceptional as a kid. He kind of learnt. And he found his style. So I think that, in a way, it’s kind of a good story to tell, because there’s so much mythology around art now and a lot of that seems to be attached to the value of things – or the price of things, I should say.

What is really great about Keith’s story is that there’s a sort of innocence to it. It wasn’t art that was generated for commercial purposes. There was no business strategy involved – even though he always had an eye on how he could make a few quid. It sort of felt like the end of an era. Those years when he was really coming to prominence, it felt like it was the end of something and the beginning of something else. It was never really about the price of things for him. He was an idealist, basically, about what art should be and what it could be and how transformative it could be. And actually I think that’s a good reason to be making a film about him now, because I think the art world now is sort of synonymous with this sort of entrepreneurial spirit. But it feels like that period in the late 70s and early 80s in New York was so alive with this spontaneous desire to make stuff.

Arena: Keith Haring, directed by Ben Anthony, will be shown on BBC Two tonight and subsequently on iPlayer