Kehinde Wiley, Narrenschiff, 2017, Three-channel digital filmDuration: 16.40 minutesEdition 1 of 5 + 2 AP

The renowned American painter Kehinde Wiley, who can soon add presidential portraitist to his long list of accomplishments, is known for his brightly patterned, hyperreal portraits of black people in heroic poses. However, his latest exhibition, In Search of the Miraculous, makes a departure from the style that made his name.

The exhibition is split between the Stephen Friedman Gallery’s two spaces, with nine huge seascapes hanging in the main gallery and a three-channel film – Wiley’s first – projected in the gallery across the road. The physical separation of the film and the paintings serves to underscore that while they both explore the relationship these black, mostly male figures have with water, there is a marked visual contrast in that depiction.

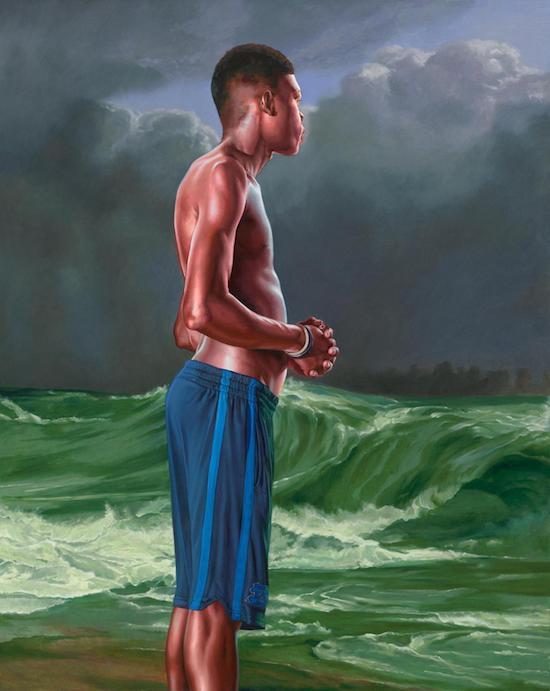

Drawing on the maritime art of the Romantic era, name-checking old masters like J.M.W. Turner and evoking Casper David Friedrich, these large and dramatic paintings portray young islanders battling heroically against tempestuous seas in small wooden fishing boats. Wiley’s reworking of Van de Welde’s Ships on a Stormy Sea depicts a young man standing on the edge of his boat, a wave crashing at his feet as ominous purple and black clouds gather above him and even more ominous ships float in the background. But the figure has his shirt off; it’s hanging with flair over his shoulders. He stares out at us and, while we can see the tension in his arms, there is no trace of effort in his face. In one sense there is a continuation of themes from Wiley’s previous work, with the air of royalty substituted here for the impression of the wayfaring hero. Yet despite the scale and drama, there isn’t the same sense of grandeur. In the majority of the seascapes these young black people look not heroically forlorn as their Romantic era counterparts, but actually quite deadpan.

Wiley’s new work also explores isolation and mental illness – which makes maritime art an apt approach. There is a well storied history of sea travel’s effect on rationality. The turbulence of Wiley’s waves reminds us of the fragility of the human form against a presence as powerful as the sea. And yet under close scrutiny the quality of the painting in some areas does not hold up, giving a paint-by-numbers effect. Diminished by under-impressive technique, the seas lose some of their menace. They are weakened further still by the physically striking figures that star in so many of Wiley’s works, the faces of which seem relatively unbothered by their surroundings.

Ship of Fools, a reimagining of a Hieronymus Bosch piece, exemplifies this dissonance. It depicts two figures seated in the boat laughing, a man holding an oar looking out towards the viewer and child with a bandaged knee, staring at the dark water. This portrait has the strongest dialogue with the film not only in that they share a name – Narrenschiff translates from German as “ship of fools” – but in that the thematic arc that (barely) holds the works together seems to exist mostly in the dialogue between those pieces.

The ship of fools is a trope from antiquity, an allegorical story about a ship with an incompetent and unprincipled crew. It’s most famous iteration, Narrenshiff published in 1494 by German theologian and humanist Sebastian Brant, is a satire riffing on the vices of society. In Brant’s version the boat is full of archetypal fools setting sail for the fool’s paradise. Hieronymus Bosch’s interpretation, rumoured to be a response to the woodcut frontispiece of Brant’s work, depicts a group of merrymakers with their gluttony on full display. Wiley’s work over the years suggests he would be loath to portray his subjects as fools, and there are significant changes in his interpretation. In Bosch’s version a pale pink flag depicting a moon flies from the tree that is the mast of the boat. The moon has long been associated with seafaring, but it also connotes inconstancy and, of course, lunacy. A 12th century poem hailing the teachings of medieval philosopher Peter Abelard warns us that while the foolish man changes like the moon and has a wandering mind, the wise man is as constant as the sun and his mind takes “sure steps”. Wiley sees the ocean as “a metaphor for people going out into unknown territory and desiring what they consider to be the best of themselves.” Aspiration and glorification are his themes. There is no moon in Wiley’s Ship of Fools and the scenes of the film are flooded instead with the reflected light of the sun.

Kehinde Wiley, Fishermen Upon a Lee-shore, in Squally Weather (Zakary Antoine), 2017, Oil on canvas, 180 x 149.7cm, (70 7/8 x 59in)

Narrenshiff depicts the sea not as a threat but as a balm. The young men look at ease here, the sun lighting and warming the waters they swim in. It’s the abundance of light in this film that perhaps helps to retroactively provide context for the dissonance the exhibition evokes. For no matter how dark and stormy the skies in the paintings are, each figure is illuminated. Borrowing from the effects of digital photography, Wiley imbues these bodies with light, adding a brilliant richness to the skin of his figures. Being “the best of themselves” means that even under terrible conditions, those “black bodies,” a phrase continually used by Wiley which evokes a horrible heaviness, appear illuminated from within.

The discourse on madness appears in the film as anguish stemming from the trauma of colonisation, described by acclaimed actress C.C.H. Pounder, who narrates the film reading quotations from Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth and Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilisation. Accompanying those sunlit and almost utopian scenes, the contrast seems to suggest that even while mired in the damaging after-effects of colonialism these young black people can still strive for self-knowledge and self-actualisation. It suggests there is the possibility of sure-footedness after centuries of wandering. The ship of fools becomes a ship of heroes on a “great symbolic voyage … in search of reason.”

But does his desire to empower take away from his own expressed grand narrative, In Search of the Miraculous’s supposed exploration of loneliness and migration? At the end of Narrenschiff a figure stands alone, silhouetted against the beach, once again evoking that phrase “black bodies”. And yet there is just enough light to resist full opacity. What could have cut a haunting figure is slightly undercut by the subtle visibility of the young man’s white vest.

While there was potential for a full-fledged exploration of madness and isolation in the Romantic tradition, it feels as though Wiley’s desire to portray these figures as beautiful, as heroes in the grandest, most romantic and idealistic sense means he does not really ever enter that space. Wiley’s earnest goal to, as he puts it, “say yes to us” (us meaning the black and brown communities) is his priority – and, of course, his prerogative.

In Search of the Miraculous is at the Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, until 27th January