White cube gallery spaces are often charged with being clinical, but the experience of stepping into Katrina Palmer’s new exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds – with its windowless gloom and the mechanical exhalation of air conditioning, feels more like walking into a morgue than a hospital.

The first room of the gallery, which sits inside the Leeds-based research wing of The Henry Moore Foundation, has been lit by the eerie artificiality of a several light boxes, each showing grainy photographs of 1950s railways semaphore signals, their originator unknown. Over the tannoy, a functional ‘bing-bong’ is followed by softly spoken platform announcements: “We’re sorry to announce a recent departure”, “Please move towards the light” and then a malfunction, “Be prepared to find the next signal at… pause… caution.” Echoes from a sister announcer in another room drift through, creating overlapping harmonies and confused instructions.

The installation is the culmination of the London-based sculptor’s research into two of the capital’s macabre and now overwritten sites, the Necropolis Line and Cross Bones cemetery. The former was a railway line departing from Waterloo solely for the dead, opened in 1854 to ferry corpses from a city whose burial grounds were bursting at the seams to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey.

If building a whole new transport network because of grave overcrowding seems extreme, bear in mind that mid-19th century London was riddled with corpse-contaminated water supplies, smallpox, measles and typhoid epidemics were the norm, and in 1848 an outbreak of cholera killed more than 14,000 people – somewhat exacerbating the problem. Not a nation to let a small thing like death disrupt an entrenched class system, passengers on the Necropolis Line were issued with first, second and third class tickets just like their living counterparts.

The second site that piqued Palmer’s interest is Borough’s Cross Bones cemetery, an unmarked, unconsecrated grave, which, as Palmer writes, is “completely overcharged with dead”. The small site, marked only with the fastening of ribbons to a border fence, contains an estimated 15,000 vulnerable outsiders – women denounced as prostitutes, their unwanted children, and later paupers who were rejected by the church. Situated just round the corner from Guy’s hospital, it’s said that many of the skeletal remains were snatched for use in anatomy classes.

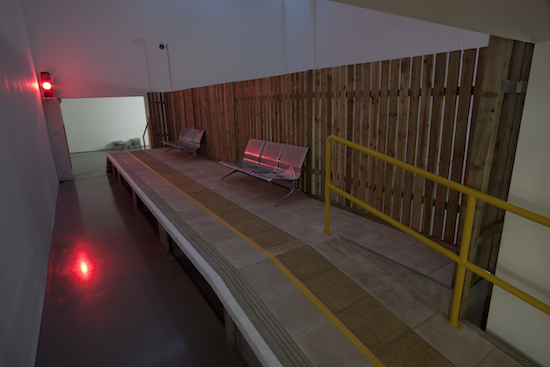

Small fragments from these histories are woven into the gallery space through both physical and sonic installations. Historical snippets, descriptive passages and surreal pseudo-announcements are piped from the second tannoy, which sits in the middle section of the gallery where Palmer has installed an authentic railway platform, complete with handrail, aluminium seating and signal box. As with any readymades, seeing the these everyday objects in a gallery context immediately makes you notice their sculptural qualities. The non-slip bobbles cast into the concrete paving and exacting yellow lines seem to become artistic flourishes.

But in many ways these physical interventions are actually just a set for the main sculptural works: Palmer’s carefully penned announcements and a collection of her writings brought together in a free newspaper, called The Line, which visitors can pick up in the space. For despite identifying as a sculptor, Palmer’s practice involves crafting objects and architecture using words instead of the hand or a chisel – equipping her audience with the tools to recreate those objects in their own imaginations.

Speaking to Palmer at the Institute, I asked about what she felt made her writing ‘sculptural’ as apposed to literary. “There are similarities,” she explains, “but I think that’s the way that a lot of contemporary art works: one of the features of contemporary art is that it can disappear into the everyday. It might be a pile of bricks that when brought into the gallery, it’s called art. It’s the same with a piece of writing. Also, I see it as sculptural in terms of the way I think: it’s always about physicality, absences, about bodies and the experiences of touch and loss, all those things that traditionally are sculptural concerns.”

Because of this unorthodox approach to sculpture, Palmer’s work has until now existed on the periphery of art galleries, usually as readings in conjunction with other exhibitions – The Necropolitan Line is in fact her first institutional commission. Saying this, her unusual oeuvre has not passed without recognition.

Earlier this year, Palmer won an Artangel and Radio 4 contest to find groundbreaking new art (Jeremy Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave was a similar commission). She took up residency in Dorset’s Isle of Portland to create End Matter, an audio walking tour, an installation and other writings, inspired by the industrial landscape rendered by heavy quarrying. Portland’s almost translucent white Jurassic stone makes it a favourite for architecture (think St Paul’s Cathedral and Buckingham Palace) and more notably memorials, the cenotaph included.

In many ways The Necropolitan Line is a natural progression from End Matter, which also touched on the themes of burial, the ground, and exhumation. Her interest in Cross Bones and its “immense subhuman mass of sisterhood” stemmed from the fact that the site is just moments away from her London home. “I’d been thinking a lot about memorials made of Portland Stone, they’re very formal things,” she explains. “And then how there was this massive cemetery in the middle of London, deep with thousands of bodies, that was totally unmarked. I thought, ‘Where’s their Portland memorial?’ I could go on and on about how women are lost in history and how their stories are buried. I wanted to counterbalance that, making this as a memorial in some way.”

The exhibition is scattered with examples of loss and forgotten stories. The photographer behind the semaphore light boxes is unknown, and one of these works is hung in a section of the gallery fenced off to visitors and only visible between the wooden posts. There’s an etching of an illuminated diagram from inside Waterloo Signal Box, which clearly marks the Necropolis Line, but we learn from The Line newspaper that despite its historical significance it has disappeared, probably into a private collection.

Palmer also plays on the idea of loss and its connection to the romantic capital of train travel. Just as lovers wave goodbye on the platform, the gallery exists as a Limbo-like state where the deceased move through ready to make their final departure. Perhaps the gallery’s service lift (opened especially for the show and fitted with headphones streaming two simultaneous versions of woozy lounge tune ‘Is That All There Is? by Peggy Lee and Bette Midler to Lynchian effect) is the final stop before souls depart to meet their maker, or in the words of the song, their “final disappointment”.

It’s interesting that Palmer has decided to focus on the platform, rather than the journey or destination, when rethinking the Necropolis Line and Cross Bones story, a decision that perhaps has more to say about the nature of her own practice. “The platform is also like a stage I suppose,” she explains. “People are kind of performing there, or participating. I hope it doesn’t feel too forced. I wanted it to be something that you suddenly find yourself in.”

Just as visitors may find themselves both audience members and performers, the installation is flooded with boundaries from one state into the next, life/death, real/supernatural, fact/fiction, romantic/violent, all are blurred to make you question their parameters. Indeed the second tannoy flits between the recognisable ‘ding-dong’ to a musical composition using the same notes. It’s an adaptation of a composition by Rachmaninov, used most notably in, Noel Cowards’ Brief Encounter – a film itself set on a platform and focused on unfulfilled transient passions.

But the true power of the installation comes from reading the free newspaper, The Line, actually within the gallery space. Some of the articles are journalistic (such as a piece covering plans to transform the Cross Bones site into a garden), some funny (a platform announcer is made redundant when she is discovered to be an automaton), some ghoulish (a Dickens short story called The Signalman that deals with phantoms on the track and false signals), and some straddle the line between fact and fiction in a way that is very unsettling.

So too is the interaction between the texts and the announcements, which work together to warp and colour the meaning of the words heard or read. Suddenly you’ll be reading a sentence about how the Cross Bones sites was a fairground in 1884, and the Rachmaninov piece will morph into a sinister fairground jingle. The arms of the signal boxes which are described by the announcer in a means akin to guided mediation, become terrifying after reading Palmer’s short story The Couplers, about a group of supernatural sex workers whose job it is to give passengers impassioned goodbyes but in fact have something far more sinister up their sleeves – namely large metal hooks. In this context, the announcement of “There’s still time… there’s no time at all” contorts from RP-delivered Brief Encounter-style sentimentality to an existential threat.

It is the realisation of how incredibly odd and unsettling the act of reading can be, that is perhaps the most important element of the exhibition. Everyday as it might be, reading is a liminal zone between two states – a sort of quotidian time-travel powered by the human imagination. You’re present both within your physical space, and in the dimension dictated by what you are reading – hovering between two time zones and localities.

It’s the augmentation of this two-places-at-once state that Palmer does so well, making frameworks for her audience to experience ‘sculpture’ but ultimately the finished work is entirely up to them. She explains: “I’m really fascinated by the space of reading, people’s imagination, and the way that we create objects and images in our minds while we’re reading. It’s so internal. It’s different for everyone no matter what text I write, I can’t really control what’s going on in people’s heads. It’s really such a mysterious space."

Katrina Palmer: The Necropolitan Line runs at the Henry Moore Institute Leeds until 21 February 2016