Just around the corner from the Palazzo Grassi and its monstrously immodest exhibition of juvenile works by Damien Hirst, you will find a quieter, subtler, and infinitely more frightening show. Katja Novitskova is occupying the Estonian Pavilion during the 2017 Venice Biennale. The title of her show, If Only You Could See What I’ve Seen With Your Eyes, is taken from a line in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982). The robot replicant Roy Batty is grilling the designer who has created his genetically modified eyes; Novitskova’s ambitious outing similarly majors in future shock. Embracing the en vogue theory of the anthropocene, she postulates scarily fictional destinations for our rampant biological experimentation and unrestrained data collection.

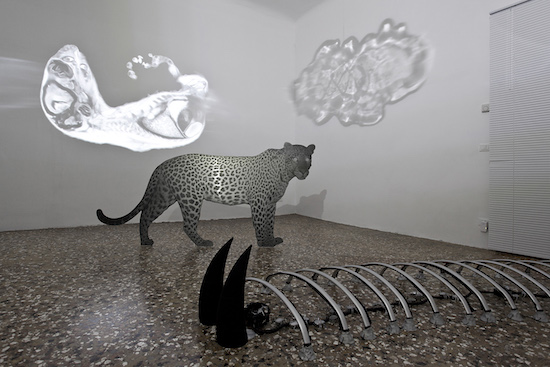

Culling stock photographic images of the animal world from internet searches, Novitskova then has these enlarged as digital prints that are sculpturally mounted on aluminium in a manner not dissimilar to that of Cady Noland. We find one of these sculptures in the otherwise empty ground floor entrance lobby that depicts a big cat standing on top of the body of a dead elephant. This is Approximation (Trail Camera Night Vision, Lioness Eating an Elephant Carcass) (2017), an image of Darwinian excess, the triumph of the strong over the weak, a metaphor – one might guess – for our human conquest, our dominant influence over the globe’s other feebler, dumber, species. Like the lioness atop the slain elephant we humans sit up on high, glaring down at our fellow creatures, thinking, how we can ingest them and exploit them? And now we have the technology to take this power to new levels. This is Novitskovsa’s territory. The night vision images highlight the eyes of her lions and jaguars – hers is an intensely ophthalmic world.

Upstairs, there are more aluminium-mounted prints where we encounter snakes hatching from eggs – reproduction is another key theme for Novitskova – and she takes this fascination to an extreme here with electron microscopic images of DNA, of roundworm embryogenesis, of fecund Drosophila fruit flies. We then enter a room with several modified electronic baby swings called mamaRoos. This, at first view, recalls entering an SCBU – a Special Care Baby Unit. There is the same sense of high-tech intensive monitoring, a fraught zone where little creatures are cosseted, nurtured. But these are sculptural forms. Works such as Mamaroo (Storm Time, Plastic Palm Trees) (2016), cradle several tiny blood-orange coloured robotic bugs rather than some pink human new-borns.

MamaRoos are rocking chairs for babies that some say provide an environment that is similar to being held in-utero. They come in different designs and have several fun-sounding rocker settings such as car ride, kangaroo, and tree swing. But Novitsokova’s room here is less playful, full as it is of these customized mamaRoos that are spookily backlit in order to throw huge and fearsome insectoid shadows. Hers is a sci-fi nightmare, a set of incubators for new forms that have malevolent intent, which may even have no place for us. These constructions too have something of Isa Genzken’s more recent plastic combine sculptures, with their brash colouring and dark humour that perverts the domestic.

Novitskova’s worry, then, is of a future where odd new species may be created. Some of the other creatures she envisions coming into existence are based on the essentially cute – she is fascinated by the popularity of winsome animal imagery on the web and how it is likely that in the future we will try to enhance certain features (enlarged Manga-style doe eyes for instance – the ophthalmic again) for our own aesthetic and emotive pleasure. Humans have, of course, been doing this for years, as with breeding cats and dogs with exaggerated features that, for poorly explained neurological reasons, hit the button that makes us swoon. This can be to the detriment of the creature itself of course. King Charles Spaniels, for example, with their bug eyes are prone to a condition called syringomyelia where the brain is too big for the skull and is thus squashed southwards into the hole containing the spinal cord.

Novitskova’s future is one where we may modify endearing animals in ways that involve biotic technology and computers – one might imagine cats fitted with Logicams scanning our homes, Dyson robot hoovers that look like dachshunds, a domestic world of robotic tentacles in kitchens gripping cups and saucers. But although it is not explicit in the works, one gets the impression that Novitskova is worried. Maybe these fears imply that collaborative robots will one day shut us out, will run the show.

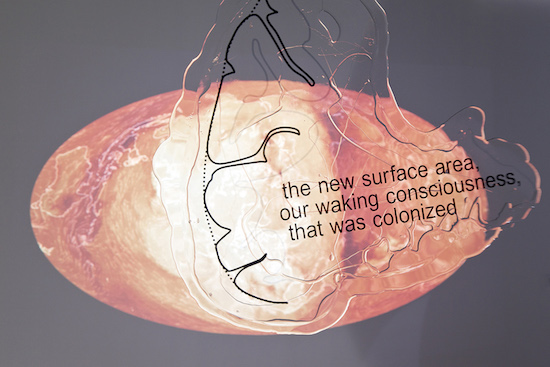

Another regular trope in her work is the exponential curve given as a three-dimensional sculptured form. The only way is up. Curves, graphs, arrows that imply… well, what exactly? That human knowledge, our incessant collection of data, is now out of control? There is a gnomic awareness in Novitskova’s work that not understanding something, that not having the whole picture, is key to her presentation of an idea of the future. You see some things you recognise, but not all.

That the Estonian pavilion is the site for these dystopian visions is no real shock in itself. Estonia is far ahead in its embrace of modern technology – enabling, for example, its citizens to vote online. With this in mind, and the country’s oft-mentioned fascination with sci-fi, it is unsurprising that in Novitskova’s art, there is a palpable sense of unease in the embrace of such techno-optimism.

Katja Novitskova takes over the Estonian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale until 26 November