Installation view of The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, Kader Attia The Museum of Emotion at Hayward Gallery. Copyright the artist, courtesy Hayward Gallery 2019. Photo Linda Nylind.

Kader Attia, the French-Algerian artist whose multimedia survey addressing the legacies of French colonialism, tells of a visit to an exhibition in Paris which explored the work of the artists who’d influenced Picasso. Picasso and the Masters, at the Grand Palais in 2009, featured Western artists but excluded the African masks and sculptures, carved by anonymous hands, that were such a revelation to the Spanish artist during his first years in Paris.

Picasso and the Masters proved to be the impetus for a series of sculptures that Attia entitled Mirrors and Masks (2013–15). These roughly carved wooden masks are partially covered in mirror shards to reflect the viewer’s face as a ‘Cubist’ construction, thus denoting the imposition of the Western Gaze in reducing as a cipher for its own desires, the colonised object. Seeking to redress the grave omission of the curators of the Paris exhibition, Attia draws our attention to the fact that the sculptors of the African carvings cannot be accommodated by a Western conception of either ‘artist’ or ‘master’. Just as it had been in Picasso’s day these deracinated objects were still, in the first decade of the twenty-first century, deemed to belong in ethnographic displays rather than in art museums, at least by French museologists and curators.

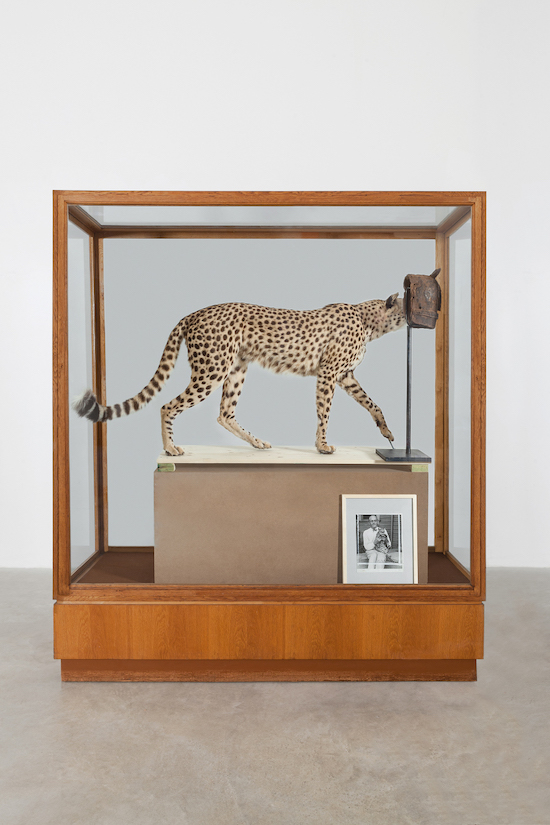

A more explicit demonstration of these racialised categories in Western museums is Attia’s series Measure and Control. One vitrine contains a stuffed cheetah next to an African mask displayed on a pole, like a trophy head on a spike. If this series comes across as a little didactic – and in many of the other works this is also true, though often in a far more positive sense of the word – elsewhere, and more captivating, are a series of cardboard cartridges typically used for the packaging of electrical goods. With the light skimming across knobbly surfaces and cavities, these make a delightfully convincing and scathingly witty stand-in for stolen and appropriated African masks.

They also make connections between the historical plundering of tribal artefacts with both Western consumerism and with modernist arte povera ideas of appropriating junk and giving it art world value. Sixty-six years after Chris Marker and Alain Resnais’s anticolonial film, Statues Also Die, a film that was banned in France for over a decade, these too are a study of a kind of death that goes beyond material ruin and plunder. The cardboard masks allude to that hollowing out of meaning and significance that has left a continuing legacy in the West, but also in those plundered countries where ‘traditional’ carvings are now created for a specifically Western tourist market.

Kader Attia, Rochers Carrés, 2009. Analogue C-Print. 78,5 x 98,5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne.© the artist

Attia grew up partly in Algeria but also in the banlieues of Paris, among fellow north African migrants who were housed in concrete highrises, which were, he says, like ‘open sky jails’ whose intent is to police, surveil and control. One of his earliest works in the exhibition, The Landing Strip, is a series of photographs of Algerian transgender sex workers in their tiny banlieue apartments. The title of the work is the name given by these occupants to the boulevard on which they work, as its long, straight road resembles an airport runway. The ‘landing strip’ separates the neglected suburbs from the centre of Paris.

The photos were taken over a two-year period, from the late 90s to 2000, and are reminiscent of images of ‘demi-monde’ New York by Warhol and Nan Goldin, where boredom, domesticity, violence and intimacy all come under an equalising gaze. Photographs from the series begin and end the exhibition, whereas a more stark confrontation with the banlieues is a recent video of Robespierre Tower. Here the lens of the camera crawls slowly up the tower block’s edifice. When it finally reaches the top the sky opens on a grey panorama.

Attia seeks to convey the claustrophobia, the suffocating bleakness, the dehumanising rabbit hutch feel of the tower, as the grid sculpture and hanging breeze-block installation nearby suggest. But the film doesn’t quite achieve that, possibly because it offers instead the rhythmic calm of repeating patterns that fills the expansive screen. And in the context of an art gallery – the postwar white cube as well as the particular location of the brutalist structure of the Hayward and the surrounding South Bank – we might wonder how it’s meant to suggest all that when the slow vertical tracking shot appears to offer more a meditation on form.

Kader Attia, Measure and Control, 2013. Series of 5 vitrines (detail). Vintage vitrine, stuffed animal (cheetah), African mask, framed vintage photograph. Courtesy of the artist and GALLERIA CONTINUA, San Gimignano / Beijing / Les Moulins / Habana. Photo: Ela Bialkowska © the artist

The strongest film in the exhibition is The Body’s Legacies, Pt. 2: The Postcolonial Body. Filmed in 2018 following the brutal and sustained assault of a young French-Congolese man called Théo Luhaka, by four police officers, it takes the form of a series of expansive interviews: academics, an activist and a journalist talk about the racialised body, as victim, object, perceived threat. Sociological analysis sprinkled with some personal insight. Is it remotely dry? Not at all. It’s among Attia’s best work yet, and this probably shouldn’t be surprising, since this seems to be a form he favours: he’s also the co-founder of La Colonie in Paris, a space for ‘art, critical thinking, debate, and cultural activism’, whose opening on the 55th anniversary of the 1961 Paris massacre marked the date when protesters for Algerian independence were targeted and killed by police.

So why is such a seemingly cerebral exhibition called The Museum of Emotion? In one gallery a jumble of black and white photos features emoting singers and musicians alongside fascist dictators and revolutionary leaders in full oratorical swing. From Edith Piaf, Ella Fitzgerald and Miles Davis, to Mussolini, Lenin, Castro and Goebbels, the wall pulses with public displays of intense fervour. But apart from what might be fairly superficial connections – twentieth century icons and/or figures of notoriety emoting, the power to move crowds, the idea of ‘fanaticism’ – what links should we make between these two sets of figures, and what does their juxtaposition mean?

Perhaps the clue lies more with the ‘museum’ part than with ‘emotion’, since it’s the idea of the museum that’s being deconstructed in this exhibition. The question might then be: what hollowing out of meaning do we need to make to put Mussolini and Edith Piaf side by side, just as we need to ask when we see Attia’s stuffed cheetah and African mask side by side. Emotion may be the ostensible subject, but what’s beyond when it comes to institutional framing?

The centrepiece of the exhibition is a vast, multi-faceted installation called The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, an installation that was first seen at Documenta in Kassel in 2012. In just one part of it a slide show features before and after images of disfigured World War One soldiers who’ve undergone primitive facial reconstruction surgery. These are paired with images of broken artefacts whose points of repair are deliberately left visible. Though the soldiers, post-surgery, still inevitably bear the horrific results of their injuries, the title of the piece suggests a meditation on a difference between Western and some non-Western ideas of ‘repair’. Meanwhile, the deliberate artifice of such a pairing carries its own formal poetry, with its brutal rhythms and counterpoints.

This is an intense and eloquent exploration of postcolonialism, looking at forms of racialised oppression through architecture, public spaces, museums, and more. Dense and visually arresting, it all comes together rather wonderfully.

Kader Attia: The Museum of Emotion is at the Hayward Gallery, London, until 6 May, 2019