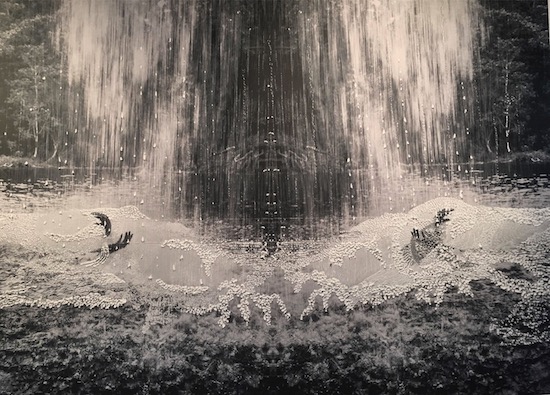

There is a dramatic backstory to Two Hands – Killen Falls, the most extraordinary piece that lurks in the dimly lit rooms of Joshua Yeldham’s new exhibition Endurance at the Tweed Regional Gallery in northern New South Wales. And it’s a story Yeldham is eager to tell: it is pretty much the first thing he launches into as we shake hands in front of this large photograph on linen paper, into which Yeldham carved patterns using his signature belt sander. Later that week, as he unveils the exhibition by giving a talk to a mostly dazzled public that has crammed itself into the gallery, he opens with the same story.

Yeldham was on holiday with his family on the South Island of New Zealand – at Mount Aspiring National Park to be precise – when, whilst visiting a popular water hole, he witnessed a man nearly drown after he leapt into the freezing water having been egged on by his friends. This man, whose body went into shock from cold, descended to the bottom of the pool, fully clothed, where he stayed for several minutes before two young Englishmen were able to rescue him and he was revived by two doctors who also happened to be nearby.

"He was a very overweight Muslim man who didn’t have swimming skills," says Yeldham, who himself ran for help and a phone signal when the man got into trouble. "His friends were praying to Allah and were in shock. Everyone was in shock and my children were screaming, so I had to get them out of the way. He was carried back to the main road and a chopper took him away.

"Many people acted. My problem, which I faced for about three days afterwards, was about me not going in the water [to save him] – normally that’s who I am. I held my own value and didn’t want to risk it, and that space created these works. The beautiful part was that at the time everyone worked perfectly in their own capability and two other candidates were picked to swim.

"I have to respect the sequence, in which now I tell the story and make the art."

And it is an exquisite thing. In this small (but immaculate) rural gallery, Two Hands hangs unassumingly around the corner from a temporary series of David Hockney pictures and indeed another Yeldham exhibition, the retrospective Surrender. Two Hands feels like the gallery’s unofficial centrepiece and dominates Endurance, a show that is the result of a residency Yeldham undertook at the gallery in February.

The seed of Two Hands came about when Yeldham and his wife Jo were swimming at the nearby North Coast beauty spot of Killen Falls. The setting reminded them of their experience in New Zealand, prompting Jo to take a photo of Yeldham submerged with only his hands above water. Back at his home studio on the northern outskirts of Sydney, Yeldham printed the image, digitally mirrored for symmetry – reminiscent of Mat Piranda’s ‘Rorschach photography’ – on to thick cotton paper and used the belt sander to carve patterns into it, a technique he has used for much of his career.

Two Hands is immediately striking on a visceral level, with its alien-like tree roots and distorted suggestion of rain, yet also rewards sustained study and time (endurance, if you will) thanks to the detail and fineness of the carved patterns, which, like previous Yeldham works such as Jude (2013, on display here as part of Surrender), offer a Polynesian, or in this case, somewhat appropriately, Maori feel. The artist’s strangely long, graceful, feminine hands hardly seem the frenzied flailings of a drowning man, and more like they are dancing or conjuring. The work has a powerful, disquieting magic, a decidedly psychedelic manifestation of that event in New Zealand, Yeldham in his peculiar way capturing its sensuality, its physicality and the forced intimacy between strangers as about 30 people joined forces to save the man’s life.

Joshua Yeldham, now in his 47th year, is a much-admired golden boy (and he is very, charmingly, boyish) of contemporary Australian art, yet one without an affiliation with any particular school, style or movement. His career need not be chronicled at length here, but following an extremely privileged, well-heeled upbringing (he attended the famous Aiglon boarding school in Switzerland, current sixth form fees: £85,000 per year) it began with him winning an Emmy and a student Oscar nomination in 1994 for his film Frailejon, a philosophical meditation on mountain climbing in Venezuela. He then spent several years living in a Kombi in the Australian desert, during which time he was enraptured by both the landscape and "line and dot", and the artist was born. Much of his adulthood has been spent undertaking improbably adventurous travels around the globe in the name of his craft – today he mentions Algeria, Indonesia, Japan and South America. His first solo exhibition took place in his native Sydney in 1996 and his career quickly snowballed, complete with nominations for some of the Australian art establishment’s most prestigious prizes such as the Wynne and the Archibald, and multiple TV appearances.

The other milestone is his 2016 book Surrender, which began as a private journal for his daughter before it was self-published and then picked up by Picador. The book is an unusual and imaginative journey through Yeldham’s kingdom – both internal and external – that showcases many of his works from down the years alongside snippets of text that describe his adventures and practice, and offer more abstract philosophical musings such as, "You have taught me to sway / and to understand / that movement leads to / evolution and ultimately / to creation".

Popular critical opinion has it that his art explores the connection between landscape and spirituality, the need to ‘surrender’ to a pervasive higher force and to channel one’s restless id towards harmonious creativity. Some may roll their eyes at this – with Yeldham at least, I choose not to – but the works themselves are utterly convincing and driven by a disciplined sense of purpose and restraint. As well, this devotional streak is often balanced by the stark expression of fear, loss and insecurity.

Some of this can be found in works in the Surrender show at the Tweed gallery – in particular, Self Portrait: Morning Bay (2013) and Bird Catcher (2008), both of which reference Yeldham and his wife’s initial struggle to conceive a child. With the help of IVF they succeeded, and there his family is in the top right corner of Self Portrait. Bird Catcher goes so far as to show a foetus attached to an umbilical cord within a womb, that then revolves as the viewer turns a pulley; with this piece can you also pluck the strings of one of Yeldham’s self-made musical instruments.

Moving through Surrender and then the fresh creations in Endurance, it becomes clear that some version of a womb can be found in many of his works – albeit generally not as literally as with Bird Catcher. Certainly in the centre of Blue Fig – Nashua, which Yeldham created after tapping into what he calls "fig tree knowledge" and which in its manipulation of ink strongly reveals the influence of Japanese calligraphy, there is a womb-like shape with, again, something resembling a foetus within it. A womb can also be deciphered in Spirit Wood, another carving into a photograph on linen paper, with that mirroring effect allowing two symmetrical branches to create a shape that becomes the artwork’s kernel. It is also highly suggestive of female sexuality.

"I’m a great believer in the dormant seed," Yeldham says, "a dormant seed under the ground for fertility that comes when you’re abundant. [But] first one must become stable, holding out, holding out, for a bit of rain."

With this in mind, Yeldham’s wombs can represent patience, in relation to both fertility and art-making, and indeed the endurance that gives the exhibition its name. He explains that the concept of endurance also refers to persistence and durability when ensconced in the natural world in the name of art – Yeldham’s method is to immerse himself in rivers, mangroves, bushland and desert to attract the muse. "I wanted to align myself to that one tree, the mangrove, with my brush and my ink, and I had my endurance to last longer, to feel connected to that moment. And that gives me a joy that is more stable than any other."

Another motif that emerges in Endurance is Yeldham’s beloved owls. Owls have featured in his multi-media assemblages for decades, originally serving as a totemic offering to some higher presence in the name of his and his wife’s efforts to conceive. By now, having fathered two children, owls mean something different. Owl of Tranquillity is a close-up portrait in which the beast’s face and features, as Yeldham points out himself, suggest an aerial view of a landscape full of lakes, tributaries, deltas and mountains. It is a sharply different treatment of the owl to Self Portrait – Morning Bay, in which the owl is Yeldham himself, the new closeness perhaps reflecting a hard-won intimacy he feels with the mythic owl.

"Now owls are symbolic of pausing, observing, not having to speak all the time, touch, cognition, consciousness, playing games, speaking with the animals."

Some critics have suggested echoes of one of Australia’s most brilliant modern artists, Brett Whiteley, in some of Yeldham’s work. This is certainly accurate, particularly in Yeldham’s landscapes such as Morning Bay – Lovers Rock (2011). But Whiteley was an artist who in part defined himself by his heroes – from Bob Dylan to Arthur Rimbaud to a plethora of game-changing painters from throughout history. He saw himself as operating in the slipstream of other geniuses. Yeldham, on the other hand, seems to exist ethereally in a sphere removed from the impact of artistic traditions. While he acknowledges that other painters have affected him, it is clear his art is born more of experiences and challenges in the wilderness, along with the beliefs and ideas he cultivates: sensuality, joy, creation and destruction, surrender and endurance.

"I feel connected to Picasso because I have eaten him and his literature and his world. I feel love, even though he’s a Minotaur – he ate things and people. I’m connected to Paul Klee. Van Gogh recently – I keep being startled by his magnetism and his energy, and the fact his theatre was for himself and not for others. I love that intimate space that he was rolling in and anguishing in."

Klee had long been on my mind in relation to Yeldham. One can plot a certain trajectory between Klee drawings and paintings such as Angelus Novus (1920) and A tiny tale of a tiny dwarf (1925) and both early and recent Yeldham. Both men are conjurers of a mystical but rather impish charm. E.H. Gombrich wrote about Klee: "… nature herself, [Klee] argued, creates through the artist; it is the same mysterious power that formed the weird shapes of prehistoric animals, and the fantastic fairyland of the deep sea fauna, which is still active in the artist’s mind and makes his creatures grow."

I put this quote to Yeldham. He says, "What a weight off our shoulders that we’re not in complete control of our authorship. How beautiful to know that there are levels of guidance that are being handled for us."

A conversation with Yeldham is a unique experience. In his sprawling but considered reflections, he verges on reverie at times, fuelled by a belief system that honours spirituality, sensuality and creativity. He is part guru, part Allen Ginsberg’s meditations on composition, and in answer to each question returns to ideas advocating communion with nature, cultivating a sense of ‘abundance’ and transcendence. It is easy to lose his thread as he holds court in his softly-spoken, measured but enthusiastic tones, yet then be struck by some mysterious or suddenly aphoristic comment: "I feel sensual, the sense of being lovingly activated in the moment, and therefore I don’t feel labour" or "I’m only loyal to the three paintings on my easels in my studio – that’s as far as I go in time or space".

The analogies come thick and fast as he aligns the act of painting and the nature of being an artist with processes and phenomena in the natural world. Chief among these is the bushfire, in which new life emerges out of destruction.

"Allow destruction," he says, "and out of destruction I then pull beauty, beauty out of something that collapses, tapping into nature’s language, which is always that new life comes out of bushfire.

"But you can’t stay in creation, and you can’t stay in destruction."

This compulsion toward destruction and ruin is reflected in the way he has reacted to his background and upbringing. The Yeldhams have been described as "one of Sydney’s notable families", with one of Joshua’s sisters a successful film producer in Hollywood and the other the director of Sydney’s Arthouse Gallery, which represents Joshua. The Yeldham siblings are a high-flying bunch, and enjoyed every material advantage as they were growing up and setting out on careers.

While expressing gratitude for his privilege, Yeldham explains how he tapped into destruction by leaving his comfortable urban existence to "explore the outskirts", referring to his restless travels and decision to live in a Kombi in the desert (the way he describes this experience in his book, as an odyssey into the extremes of nature and a rejection of civilisation, has echoes of the doomed Christopher McCandless). He says he feels an affinity with the myth of Robin Hood, who, Yeldham explains, was brought up wealthy but departed to live on the fringes. He cites the same story for the Buddha, saying, "Those characters left the city because they felt there was something beyond that, something beyond the worlds of materialism."

From here, conversation eventually turns toward what Yeldham perceives as essentially Australia’s ongoing tall poppy syndrome.

"The Anglo-Saxon thing in Australia is that, if you have privilege, hide it, because so many people had to struggle to survive when they first came to Australia. Australia is still growing out of its infancy when if a farmer had a windfall from selling wood, you kept it to yourself because of how barbaric it was. We still have elements of that in our culture."

I ask if this applies beyond financial achievements and into the world of artistic endeavours.

"If I said that I’d painted some magnificent pictures this week – they’re magnificent – it jars with people that I can feel such magnificence and they say ‘oh you’re full of it’ or ‘it can’t be that good’. This is where we’re leaning on the destructive sequence."

There is probably some truth to this, but I confess to being momentarily jolted out of dreamlike Yeldham-land by these comments. To lament an inability to embrace open self-celebration, to my grizzled outlook, seems crass at a time when the most prevalent model of such a thing is the crowing, braying, warped peacock that is currently American president.

This reservation begins to subside, however, by viewing Yeldham’s sentiments as coming from, as he would put it, a place of love and abundance. By reporting his own "magnificence" he is attempting an act of connection and intimacy, and coming from him – and probably not from many others – this is not alienating or braggartly. In proclaiming his personal victories, he is more celebrating the things all people are capable of, the possibilities of life, than broadcasting and affirming ego, or indeed perpetuating the myth of the touched or elevated individual artist. That’s one way to read it anyway.

Another factor is that as well as existing outside the parameters of art movements, Yeldham in many ways floats free of the socio-political sphere with his simple devotion to exploring nature and his family. You could, I suppose, say he lives in his own world, and that his creations, including <i<Two Hands, approach outsider art or folk art (he received no formal training – just a grounding in filmmaking from Rhode Island School of Design), though it is hard to be thoroughly convinced by this given his schooling and background. Certainly he does not seem to play the contemporary art world’s game of cliques and commodities, and he does not speak its parlance.

All this is not to say, however, that political elements can’t be read into his work. The frankness of his book can be seen as subversive, as he openly details the trials of infertility and the bullying he was subjected to as a child. It can be a discomfiting read, but the unflinchingly honest self-examination decisively cuts through a mainstream public discourse driven by ideological agenda and brand narratives. And the fragmented looseness of the allusions to his personal life generally invalidates any accusations of over-sharing. Such self-analysis is at the heart of Endurance,/i>, particularly with Two Hands and its foundations in Yeldham’s decision not to jump into the water after the drowning man.

Though he left the Tweed Regional Gallery’s residential studio in February, it’s as if the residency has been going on in Yeldham’s mind ever since then as he developed the ideas from in his home studio. It has been, and continues to be, a fecund year.

"You’re seeing the product of an intense period of six months – I’m also painting another show for Sydney. You’re seeing a man that is in full swing of manifesting power. So right now I’m not in post-show destruction mode where I’m dealing with not making anything anymore and I don’t quite know where to go. That interview would happen in January when I’m in full flow trying to find an algorithm that would get me back into finding charm, and then off I go again.

"So the bushfire analogy is primal to me. At some point I’m going to just burn off, everything is going to look smashed, but I know my seed structures pop and all I have to try and do is endure the timing until the rain comes and I sprout new life."

Joshua Yeldham: Endurance is at Tweed Regional Gallery, Murwillumbah, until 10 December. Surrender is on until 19 November