Joe Coleman cuts a unique figure against whichever cultural backdrop art critics may attempt to place him. Born in Norwalk, Connecticut in 1955, the painter, performance artist and collector of sideshow oddities has lived in his adopted city of New York for much of his adult life. Part sideshow carny (both ringmaster and geek), 70s punk rock performer with The Steel Tips, firework toting prankster in the guise of Professor Mombooze-o and “fish-fucking Satanist” in the eyes of the US police. Coleman represents a singular link between the painters of religious iconography of the past and the post-internet information sickness of the present era.

Working on a single square inch at a time for eight hours a day, Coleman’s paintings are hyper-dense with data. Text and image collaborate to produce novelistic narratives, interweaving personal events and pathologies with alternative takes on American history. His best works balance ecstatic beauty and infernal pain in equal measure, repelling the viewer with aspects of his subject matter whilst simultaneously drawing them in with idiosyncratic yet stunning technique that allows for the unveiling of many layers of precisely structured detail.

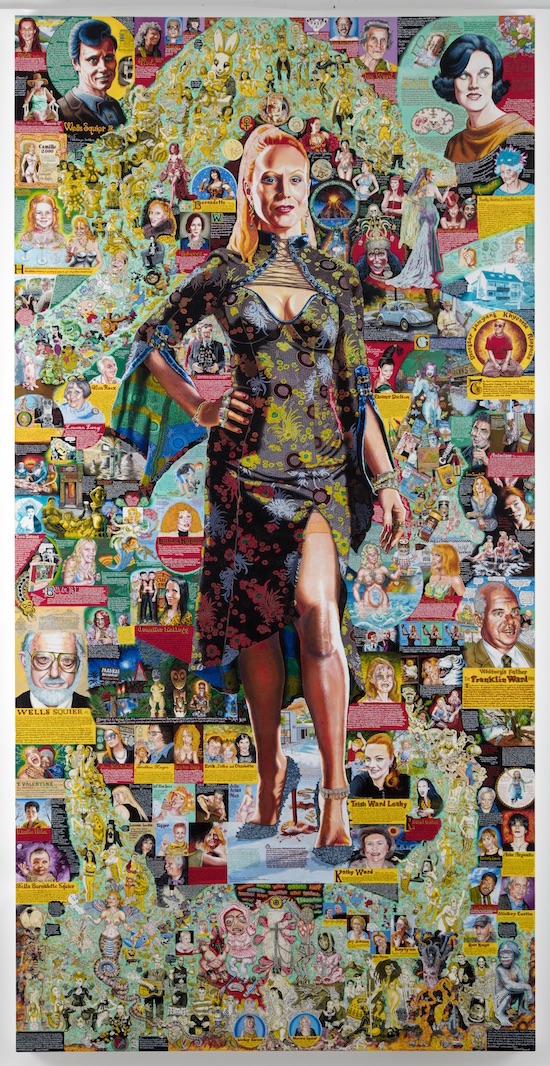

His most recent paintings show just how far that technique has developed. Both larger and even more exquisitely detailed, they also make explicit a clear romanticism that at times had been obscured by the inherent darkness of the images with which he works.

Long collected by the likes of Iggy Pop, Johnny Depp, Jim Jarmusch and Leonardo DiCaprio, interest in Coleman’s art has been steadily increasing in recent years. To his fans he is the real deal, an icon of individuality and chronicler of marginalised histories. His counterculture credentials approach those of William Burroughs, whose work shares many similar themes.

Coleman spoke to the Quietus over the phone, from his home in Brooklyn, about recent and future exhibitions, the notion of outsider art, TV as god, Charles Manson, conducting autopsies and exploding at high-school reunions, amongst other things.

Can you talk about the Unrealism exhibition that’s just been on in Miami?

Joe Coleman: It’s finished now but there’s a book that’s going to be coming out about it. I recently got involved with [American dealer / curator] Jeffrey Deitch, and he had seen me working on the painting of Whitney. There were two paintings of mine in that exhibition. Each one took around four years to complete, working on a square inch at a time. One is of my wife, Doorway To Whitney (2015), and a self-portrait, A Doorway To Joe (2010), and Jeffrey thought that it was important to have these paintings in the exhibition that he was doing with [Larry] Gargosian.

I was certainly honoured to be part of it, but as to what Unrealism is, I don’t know. My work’s been put into all kinds of categories in the past. Everything from outsider art to outlaw art. Now Unrealism is the latest category. I think though that the work itself stands outside of any category.

Rebecca Lieb said in her review of the exhibition that: “Joe Coleman may have finally entered the mainstream with this show, but he’s there strictly on his own terms.” How do you feel about that?

JC: I certainly would agree with what Rebecca Lieb says. I mean, I never made a decision to be part of any particular movement. I’ve worked with many different galleries. I’m usually accepting of anyone that I work well with, who gets the work.

I’ve worked with outsider art dealers before and also some mainstream art dealers before, like I did a big exhibition of my work with Jack Tilton and then that exhibition got picked up and brought to Europe. It was in Palais de Tokyo in Paris and then got brought to Berlin, which was my biggest exhibition, over four floors at the KW Institute.

In a way also, it has been in the mainstream art world before but I guess Gagosian and Deitch are probably two of the biggest names in contemporary art, so I guess in that respect it would be true. But I’ve been doing this work for a long time and it’s not surprising that they felt it was time to highlight it.

I’m a big fan of all your work but the new picture really is incredible. Your work is getting bigger and also more detailed. How do you get that wonderful glow that your paintings have?

JC: It’s the way that the colours compliment each other and the way I use image and text. I spend 8 hours working on just a square inch. There’s no sketch involved, so when I’m painting I’m not concerned with the whole image, just the particular area I’m working on. I let the painting tell me what it’s about. Things that happen in my life might appear in that painting, so it’s like a diary as well.

You recently contributed to a panel discussion in New York in January this year on outsider art. How do you feel about that term being applied to your work?

JC: I guess I’m happy that there’s interest in the work and the outsider community has always been fascinated with it. I’m not even sure if I know what an outsider artist really is. Certainly I know about art history and I wouldn’t consider myself in any way naïve, certainly not on the level of technique. But I guess that there are other outsider artists that also have pretty amazing abilities, Adolf Wölfli and Henry Darger certainly. I think their work is beautiful and really well crafted.

I can see something in Wölfli’s paintings, the mandala-like aspect, that you also use.

JC: Yeah, though I was also influenced by the Tibetan and Hindu religious painters. The religious painters, the Christian and the far eastern religious painters both inspire me, because the story telling aspect is so prominent too. There’s also feeling of a kind of flat perspective that I really like and I think Wölfli has some of that quality as well and I’m just drawn to very obsessive work.

On the panel discussing outsider art, there was an art therapist from Bellevue Hospital Centre, Irene Rosner David, and I was talking to her about this painting I did when I was having bouts of anaphylaxis. None of the doctors were able to discover what was causing it but it was such a severe reaction that I would have to go to the hospital. First I’d break out in hives and then my fingers swelled up and eventually you can go into cardiac arrest.

So I did this painting about it and I mounted the painting on one of my hospital gowns and I also used objects, almost like fetish objects that relate to the painting, that I attached to the frame, like my IV. The whole time I was working on the painting I had no attacks. I had them before and after but not during the process of painting it. So I do understand the idea of art therapy and certainly I’ve used it throughout my life as a way of dealing with my own personal demons.

I don’t know, though, why I get called an outsider artist. But that’s not really for me to decide. That’s for someone else to decide. I’m more concerned with doing my work.

In other interviews, you’ve talked about when you originally showed your work to galleries and they said to you “that’s not how you paint, you do the whole picture and bring the details in later on.” If you’d have gone through the normal art education system, you would have perhaps had what is special in you eroded.

JC: I think that’s right. The arts editor of the Huffington Post said that she thought I was an outsider because of the individualistic quality of the way that I paint and all of my choices that are very personal. And I said that I was OK with that.

Has the process, the two-hair brush, the jeweller’s loupe, painting with acrylics on finely sanded wood etc, changed throughout the years? I certainly can’t think of any contemporary artists that deploy the level of detail that you do.

JC: Some of the early Renaissance painters maybe. The process has changed over the years. It was very detailed, ten years ago, but every time I start a new work, I’m digging for more and more information. My digging is done with the finest brushes but also, it’s much like an archaeological dig inside of me because it’s bringing out things that are inside so that they appear on the surface. I do use the jeweller’s lens in order to try and find that space and my fingers barely move at all while I’m painting.

At the same time that the work is getting more detailed, it’s also getting larger. The two works that I’ve recently completed are the largest I’ve done and also the most personal. I like to challenge myself. To me, the work is like my religion and I’m committed to it. I was brought up with this idea of faith in Catholicism and whilst I no longer have faith in Christianity, I do have a faith in my work and I trust it will teach me what it needs to.

That’s why I can work on a square inch and not worry about how it’s going to come together. Because it does come together, and it will tell me what it needs, and I just have to be attuned to it.

Are there any more exhibitions planned in the near future?

JC: The next big thing is going to be a major retrospective of my work on the West Coast, at California State University Fullerton, which opens in March 2017, so I’m excited about that. Those two recent pieces will be there with many of my works. Not all, but a large body of the work from the 80s to the most contemporary. There’s nothing planned for Europe right now but what often happens when you do a museum show like this is it gets picked up elsewhere.

I would love to do a show in London. I haven’t done a show in London for almost 20 years. It was at the Horse Hospital. I really admired the way that they hung the works, chained from the ceiling, so you could actually walk behind them as well. As it’s interesting to see the way that the back of the paintings are.

Like, when I mentioned the hospital gown in the painting I was working on, you can only see that between the picture itself and the frame, but if you walk behind, you can see the hospital gown attached to the back of the painting.

It seems obvious from other interviews you’ve done that you don’t feel much kinship with other contemporary artists. Do you feel closer to the religious iconographers, like Grunewald, Gustave Moreau, van der Weyden, Bruegel, those kinds of people?

JC: Absolutely. Grunewald is maybe my all time favourite but obviously Bosch and also artists like James Ensor and Otto Dix. I was in an exhibition where they showed my War Triptych(2003) with Otto Dix’s War Triptych(1929-1932) and that was an honour. I got to be in a show with Hieronymus Bosch too, in the Deutsche Mark museum in Holland several years ago.

I’m less interested in contemporary art though. Conceptual art, maybe at one time it was interesting, when Marcel Duchamp was doing that kind of work in the Dada era of art, but for that to be the main body of contemporary art? It was phoney to begin with and it’s kind of pathetic.

I don’t see how that kind of work can retain any type of value in the future because it’s a game. There’s not enough soul and commitment. It’s so cynical. There’s no real faith in the art itself.

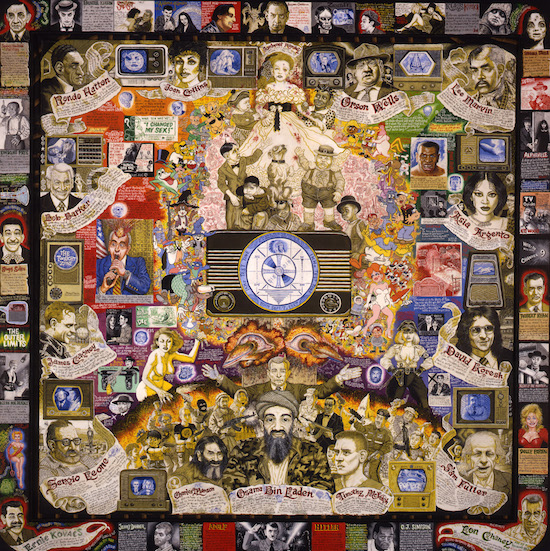

Can you talk about some of your works in particular? One of my favourites, to start off with, which has a prominent conceptual element, is As You Look Into the Eye Of The Cyclops, The Eye Of The Cyclops Looks Into You (2003). It actually has a soundtrack that runs with it I understand?

JC: Yeah, which you wouldn’t be able to hear unless you see it exhibited. That’s one of my favourites too. TV is our god, it tells you what to eat, what to drink, who to vote for, when to laugh, when to cry, when to go to bed, when to wake up. And it’s an entertainer, it’s a babysitter, it’s propaganda. I realised how powerful this god was, so I had to make this altar to the god of television.

I grew up with all of these figures from the television and I put all of that into this loving idol. Soupy Sales, Popeye the Sailor. I remember as a child, watching live on television, Lee Harvey Oswald being shot by Jack Ruby after we had just come home from church. I remember having this great time with film history, watching Million Dollar Movie or the Late Late Show and watching the Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits.

What other paintings of yours would you pick as favourites?

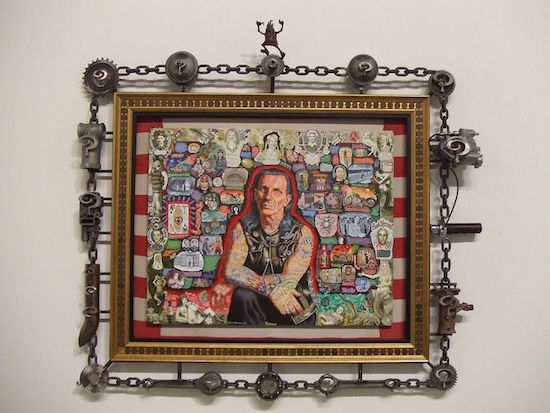

JC: The painting that I did of my dear friend Indian Larry, Indian Larry’s Wild Ride (2005).

He had always wanted to do something with me but it was after he died that I decided to do this painting about him. It was a very personal one and I used parts of different motorcycles that he was working on that he never completed, to make the frame, and I collected all these Indian head pennies from various friends and relatives of his to mount around the frame. It was the beginning of me starting to do these very personal subjects.

I had done pieces like that before but a lot of them dealt with American history and outlaws of America and although Indian Larry was an outlaw himself, it became a bridge to the more personal work I started doing. It also marked a point where the detail and research was becoming more intense. Interviewing family and friends and so on. Each one of the paintings requires the same amount of research that goes into a novel.

With the portraits of yourself and Whitney being such personal things, do they get sold to the people on your waiting list, or do you ever feel that you want to keep them yourselves?

JC: All of my work gets sold. To me it’s like I gave birth to them. It’s like I raised them and when I’ve completed them, then I want them to go out into the world and have a life. We don’t have any real kids but the works are like children and you want them to have a life.

When someone calls me up and says they’ve found a new detail in the painting that they hadn’t seen before, that’s a wonderful thing for me. It’s like knowing how your kids are doing out in the world.

The main figures in your paintings are real people, often taken from a historical context. But the supporting cast, are they faces that you make up?

JC: Well it depends. When I’m doing my research, say it’s someone who’s dead, then I would like to try and find a picture of them, but if there’s nothing available, then yes I make up their faces.

There was one instance where I was doing a painting about Quantrill’s Raiders. William Clarke Quantrill was a guerrilla bandit fighting under the pretence of being part of the Southern army during the civil war but he used it as an excuse to pillage the Kansas and Missouri Border. Some of the men that rode with him, who were very young at the time were Jesse James, Frank James, Cole Younger. He was the one that taught them the profession.

There were quite a few people that rode with Quantrill and some of them I couldn’t find any reference to exactly what they looked like but I knew about them and had read about them, so I had to make up some of their faces. But when I’d almost finished the painting, I finally came across a portrait of one of them and I had to go repaint the image because he didn’t look quite like how I’d imagined him.

How would you describe the motivation behind your choice of subject matter?

JC: A lot of the characters I paint, I feel were people who represent a true part of America that isn’t taught in history, but should be. Like for instance, Boston Corbette. Many Americans don’t know who he is, but he was the guy that killed John Wilkes Booth. Much like Jack Ruby killed Oswald. He was a fascinating figure.

He was a religious fanatic who only had sex with a prostitute and castrated himself and during the Civil War he was a very highly decorated soldier and was captured and put into Andersonville prison. And he escaped twice. Then, when Abraham Lincoln was shot, he was one of the first to volunteer to hunt down John Wilkes Booth. And then, against orders – they wanted to take him alive to uncover the conspiracy – shot Booth, and when asked why, he said: “God told me to.”

He was imprisoned but later released and called a patriot. He would sign autographs and became a bit of a celebrity, but became more and more strange in his behaviour. He had had a job as a guard in the Senate but then ended up running in there with two guns and started shooting at people. They arrested him and put him in this insane asylum, which he also escaped from.

Since we’re talking about outlaws, I know there’s a quote from Charles Manson on your site, how did that come about? Did you correspond with him?

JC: Yeah, I first sent him my underground comic The Mystery of Woolverine Woo-bait (1982) and that’s when he called me “a caveman in a spaceship.”

If you think about it, I’m using these kind of primitive tools, because in contemporary art they’re using computers and modern gadgetry but I’m using very simple methods, like they were doing in the medieval era. But I’m doing it with a very contemporary edge to it. And I think, in my mind, that’s what he’s saying.

You’re well known as a collector of unusual artifacts, which you house in your ‘Odditorium,’ how did that begin?

JC: I’ve been collecting these things my whole life and the collection is a work of art in itself. There will be a collection of these things at a place called The Morbid Anatomy Museum that will open in November in Brooklyn. They’re doing a catalogue for both shows too. They’re doing a catalogue for my collection and one for my painting retrospective.

And there’s this other wonderful project I’m doing, too, with Monte Beauchamp, which is a very unusual book project where they’re going to reproduce all of my paintings in their original size. So even the really big ones of me and Whitney are going to be fold-outs. The idea is to have it ready for the museum shows, around March of 2017. It’s really exciting for me as it’s a way for people to see my work in a way that at least is closer than any book could show you.

The documentary, RIP: Rest In Pieces, has some great stories from your performance art days. Do you have any favourites?

JC: I guess my favourite is the high school reunion one. It wasn’t my high school, it was some fans of mine that were following my exploding performances and they invited me to their high school reunion. There was one guy they went to school with that looked something like me but he had died in a car accident. So I went along as him, Doug Sprag, and then I exploded.

It was a madhouse. In the smoke and cacophony and confusion, I walked out. Then the cops got there and everyone there was saying “Doug Sprag blew up.” So the cops then had to go find Doug Sprag only to discover that he had been dead for five years [Laughs].

The other part of the film that was really shocking, was when you performed the autopsy. How were you allowed to perform an autopsy, and how did that affect you?

JC: I was only able to do it as this was in Budapest, Hungary. I couldn’t do it in the United States. The medical examiner was a big fan of my paintings and the director of Rest In Pieces had done a documentary about him, so he gave me permission to do this autopsy and he was there throughout the entire process.

To me, it was overwhelming. There were so many conflicting emotions, crossing boundaries that Janos, having trained for years, doing this every day, has had to shut off parts of his psyche in order to do this kind of work. Nothing was shut off with me. I just went in there cold and this woman that I was working on was probably the same age as my mother would have been at that time in my life, so it was a very strange experience of returning to the womb, in a way.

It was one of the most awe inspiring experiences in my life, on many different levels, both being frightening and fascinating. And it brought up so many different things that are still spinning around inside of me. It was an honour that he let me do that. He said that I could have a job there if the painting didn’t work out. I don’t think I’d want to do that every day. Although when I was younger, I was thinking about becoming a doctor.

When we were talking earlier about labels for your work, it seems that there are so many shamanistic aspects of what you do, I think that’s perhaps a better label than outsider artist.

JC: Yeah, I agree. Not only in the paintings but in the performance and in the collecting, there’s shamanistic elements to all of the things that I’ve done and they all spring from the same kind of place, the same kind of things that I find enlightening.

More information about Joe Coleman’s art and life can be found on his website