The room is dark. There are no more than a dozen people here at Hackney’s Space Building, variously standing, sitting or leaning against the walls and the few pillars that interrupt the space. Over the course of the next two hours, some of them will leave, others will arrive. Around and amongst them walks a man in a leather jacket, blue jeans, and a grey sweatshirt. In one hand he holds a bottle of water and in the other a mobile phone. He stares intently at his phone, reading aloud. “There is a briefcase on the seat next to me because I am on my way to work,” he says. “Now my arms are raised because the rollercoaster is beginning to plunge at speed.”

The text continues interminably. It seems to inhabit a kind of fevered present tense. “Now I am walking down a row of cubicles… Now I am holding out my hand to present my credit card… Now… Now…” A bewildering parade of images and events – gun-toting Mexican bandits, panoramic waterslides extending above urban landscapes, trucks full of snowmen, and a succession of attractive women. The story loops, fragments, and repeats itself obsessively. It is at once dreamlike, strangely compelling, and mind-bogglingly dull.

I’m afraid I wasn’t able to stay until the end, I admit somewhat cautiously when, a few days later, I meet the artist Jeremy Hutchison who wrote and narrated this curious story.

“Good!” he says. “Some people did and I was slightly worried…”

Did it change, later?

“It looped, and looped, and looped”

And at the end?

“I walked out of the room and it carried on. I kept on walking.”

The performance in question, entitled Forever Youth Liberator (after an Yves Saint Laurent skincare line with, according to Hutchison, “the most perfect name for a product”), sprung from the artist’s realisation that the protagonist in the overwhelming majority of television adverts was white, male, mid-30s – essentially, a demographic description of himself. The work became “an enquiry into what it would mean to then locate myself within each of these adverts, moving through this hermetic and highly mechanical landscape of signifiers.” The narrative, then, is simply the agglutination of story fragments from dozens of these ads, strung together like worry beads on a möbius strip. “So the sense of boredom that it might have conveyed,” Hutchison admits, “was unfortunately necessary for the piece.”

Engaged for the past six months in a residency at the White Building in Hackney Wick, Hutchison occupies a few feet of space between two desks and a floating wall. On one desk sits a pad of sketches, on the other a Macbook with an additional monitor, and around and about hang strange little moulded clumps of spongey yellow foam, studies for an ongoing work about earthquakes and vestibular dysfunction, maquettes for an imagined future architectural implosion.

“The White Building is Olympic legacy,” Hutchison says. “This is London’s tectonic plate at its most active,” where battery farms and waste management centres rub shoulders with hot desking tech start-ups and industrial chic pizza and craft beer bars. “There is a co-existence which is clearly not going to be here forever,” he says, but it is “a nice moment to think about – where the simulation is in tandem with the actual thing.”

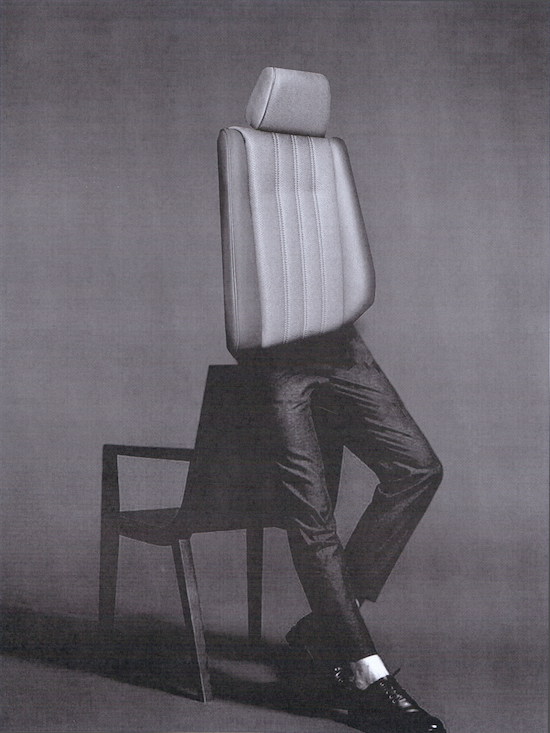

I first came across Hutchison’s work at the London Art Fair back in January, where the mezzanine of Islington’s Business Design Centre housed something called Art Projects, a subsidised section of the Fair for emerging galleries. There a Worcester-based gallery called Division of Labour displayed a meticulously curated selection circling around themes of surveillance, privacy, and transparency. Nestled amongst works by the artist duo Cornford & Cross and a six-hour film by Céline Berger of a group of extras hired to sit in a waiting room and do nothing, were a series of images by Hutchison collaged from advertising materials, seemingly depicting a new high fashion menswear line of pret-a-porter car seats.

These images are part of a project called Optimum Performance. In a short text that Hutchison emailed to me soon after, he explains that they were “triggered by a photograph I recently found in an online newspaper. It was taken from a report made by Balkan border police. The image showed the inside of a Mercedes car. The headrests of the front seats had been partially torn open by police, revealing a human body hiding inside each seat. By obscuring themselves as objects, two Syrian men had attempted the crossing into Europe.” For Hutchison, this image “glimpses the logic that determines our global order,” in which the circulation of human bodies is subject to restrictions that inanimate objects in the form of consumer goods needn’t worry about.

When we meet, later, he tells me about Henri Bergson’s essay on ‘Laughter’. Writing in 1900, Bergson believed that humour tended to arise from “a certain mechanical inelasticity, just where one would expect to find the wideawake adaptability and the living pliableness of a human being.” Why do we laugh, Bergson asks, when a man trips and falls but not when he chooses to sit down? Precisely because of this “rigidity of momentum”, this object-like quality that arises in the former instance but not in the latter. Clearly admiring of the contemporary stowaways he found online for their ability to swerve “economic and political structures to acquire a form of mobility,” Hutchison wonders if there might be a paradoxical kind of freedom to be found “in inhabiting this comedic mode of becoming an object.”

Recently, Hutchison has been experimenting with packaging himself up like an object. “This is actually a packaging material called Instapak,” he says, gesturing towards an assortment of bulbous off-white forms scattered about the floor of the studio. “It’s really great. It comes in a jiffy bag kind of thing and you have to pop it and it expands.” According to the website of the Sealed Air corporation that manufactures it, Instapak offers a “fast, easy and versatile process” capable of instantly producing “moulded cushions for products that require a consistent, precise fit and superior product protection for either high or low volume needs.” Hutchison first discovered the stuff when he ordered a new TV set for delivery. “These,” he says of the pock-marked ivory shapes on the floor, “are moulds of my anatomy in different ways.”

These moulds were initially created for a piece called Work the Meat, Pleasure the Dessert, a four-day long durational performance which immediately preceded Forever Youth Liberator at Space. In the end, he didn’t use them. Instead Work the Meat… featured, on one wall, a film of a series roughly 3D-scanned images of Hutchison’s body rotating in a kind of grey virtual space, and on the other, an LED ticker whose scrolling text in bright blues, yellows and pinks would say things like “Meat presents genuine warmth in job interviews” or “Meat is comforted by store lighting”. Between these two, sat Hutchison himself, somehow processing the “psychic waste” issuing from the LEDs, pinioned by the objectified form of his own body behind him.

“I’ve been doing CBT for the last few months,” he tells me. “Something in CBT is called Voice Dialogue Training, which is a process where you identify the different individuals which constitute your subjectivity, so in my case, I’m a father and a son and a brother and an artist and a joker and a perfectionist. You have these modes.” Separating out these different modes is seen by the Cognitive-behavioural therapist as a useful way of compartmentalising the self – putting yourself in boxes, as it were – so you can draw on the appropriate resource at the right time. Out of this process came Meat.

“I became interested in the idea that you could author a subjectivity,” Hutchison says. “To manufacture a self. So I manufactured this self called Meat. Meat is the self that does all the value-producing, affective labours, all the responses to highly mechanised triggers.” He attributes this desire to outsource the emotions elicited by advertising to a “revolt against the idea that my love for my son and my partner might in any way intersect with this culture that wants me to change my shampoo.” So Meat can take pleasure from the bevelled edges of shiny products. Meat can feel shivers down its spine at the John Lewis ad.

“They are real emotions,” Hutchison says, “I accept that. It’s impossible to hide from these feelings, and from the perpetual solicitations of capital. But perhaps we can find a mode of resistance on the psychological plane – by subdividing the self. By creating a psychic trashcan, if you like.” That psychic trashcan he called Meat. For four days he inhabited that space, attempting to channel all the affective waste of consumer culture through it and out of his system.

“It’s really, really deeply ingrained with me. On the escalators, on the tube, going down – I often look at other people and they seem to be just going about their business, but I’m totally fixated on the advertisements.” One of the LED tickers messages read “Meat taught itself to read using the Argos catalogue”. “This is true,” Hutchison confesses. “As a tiny child I would leaf through those pages, filling them with infantile wonderment.”

I tell him he should consider installing ad blockers on his internet browser. “I kind of need it,” he protests. The constant haranguing of advertisers, the emotional vampirism of consumer capitalism. “It’s quite central to my enquiry. I don’t want to talk from a position of radical exteriority.” Rather than try vainly to escape it all, better to creep inside and by inhabiting it, hope to subvert it. “The contemporary form of sabotage is less about breaking machines,” he says. “I think it’s much more about a destruction of the symbolic order: intervening in the circulation of images. That can operate as a much more effective mode of disruption. Embroiling yourself in the fetishised language of the marketplace – it’s somewhere I like to play, to swim among it, but not quite to work on its terms.”