As Matias Aguayo’s song has it – no, I don’t smoke. But I’ve often wondered about the addiction. What makes otherwise bright heads, sensible souls like chest physicians, vascular surgeons, writers and artists, clever people who know all about the risk of cancer and amputations, light up? Jac Leirner smokes and collects the fall out. She makes art from the gubbins: old butts, cellophane packet wrappers, rolling papers. Perhaps this detritus and what she makes from it all is one of the few good things to show for a life of smoking.

The nugatory materials Leirner uses remind us of Arte Povera, the Italian art movement of the 60s noted for its use of ‘poor’ or everyday materials, but there is a rich sheen in much of the display here at Edinburgh. Indeed money itself features in one of the first works to grab your attention – Blue Phase (1991) – a floor based sculpture formed featuring two serpentine lines made up from thousands of obsolete banknotes in a horizontal stack threaded together with steel cable. The minimalist floor works of Carl Andre are thus neatly referenced and gently subverted by the use of money as material.

In a nifty curatorial move at Fruitmarket Blue Phase is framed in the room by startling wall-mounted works. Little Light (2005/2017) is a couple of miles of copper electric cable nailed to the wall in a tightly wound grid with a plug on the lower left hand corner and a lit light bulb at the upper right. Opposite we find 120 Cords (2014) – which is exactly that – 120 cut sections of coloured plastic, nylon and fabric rope, some done in monochrome, others feature lurid banding reminiscent of tropical snakes. Leirner is a talented colourist and her skills are brought to a pitch with both 120 Cords and Leveled Spirit (2017) – a corner mounted array of 38 spirit levels in varied lengths arranged in a highly pleasing rainbow configuration.

The tools that Leirner uses to manufacture her works are economically incorporated too as with Metal, Wood, Black (2017) – another wall-mounted work, this time comprising 66 rulers of varying sizes each placed vertically in a line. Elsewhere there is a wooden X shaped sculpture that stands alone – Crossing Colors (2012) – planks painted candy pink and tangerine that recall John McCracken’s elegant structures. The sculptural works are interrupted at various points by neatly executed watercolours such as Color Studies (2016). These are deceivingly simple abstractions, smears of pinks and cadmium reds that have something of the darting optical effect of tiny fish in aquaria.

And then there are the smoking-related works. Leirner uses, again with great economy, the quotidian materials that form the life of a smoker. Thus we get the use of humble butts as with The End (2016) – a construction of steel cables that span one room each threaded with lines of used cigarette ends. What one is used to seeing as utter garbage – the litter of douts that scab and uglify our streets and spaces (22 billion on Greek beaches alone apparently!) is transformed by Leirner’s magic into an installation that recalls Mona Hatoum’s threatening electric wire construction Home (1999). There may be autobiographical implications to The End and the work calls to mind Will Self’s words when writing in the foreword to Gregor Hens’ excellent essay on addiction – Nicotine (2011): ‘…the very repetitive nature of smoking calls forth anecdotage…it’s the way a smoking habit is constituted by innumerable such little incidents – or ‘scenes’ – strung together along a lifeline, that makes the whole schmozzle so irresistible to the novelist.’ Self might well have added that such irresistibility clearly extends to this contemporary conceptual sculptor from Brazil.

Jac Leirner, The End, 2016. Installation view The Frutimarket Gallery 2017. Courtesy of the artist, Fortes d’Aloia & Gabriel, and White Cube. Photo Ruth Clark

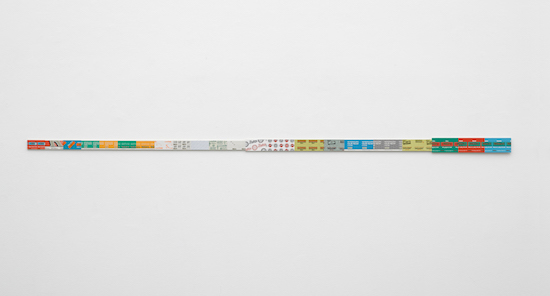

Leirner’s work is obviously influenced by the quizzical constructions of Eva Hesse and the scrupulous markings of Agnes Martin but she takes their innovations and refines, even tightens, their self-imposed constraints. No material from Leirner’s smoking habit is excluded from the party – there are several works that feature undistinguished rolling papers. She has lines of boxes of these wall-mounted on plywood, such as Flash Filters (2016). Here we see a long thin construction in gratifying bands of white and yellow, green and blue like a low rent Donald Judd. These are the covers of the box packaging with their texts and inscriptions on show – often with the figure 5, à la Charles Demuth, in bold if not in gold. Another such work – Five To Go (2016) – has an illustration of an outstretched hand on many of the boxes with five fingers waving at us. And in Simon Bird (2016) we recognize the name of one manufacturer – Rizla – a miniaturized riff on Warholian repetition.

Leirner made an entirely different construction from her collection of ashtrays that she has nicked over many years from the side arms of aircraft seats. This, Corpus Delicti (1992), is again floor placed. Atop several layers of bubble wrap are planes of glass and on top of these are the metal ashtrays – in turn these are linked together by chains. The boarding passes of the flights are also placed under the glass. If using this junk wasn’t enough evidence of her gasper habit she takes her ideas to the limit by using the rolling papers themselves as substrate. And so we get the enormous Agnes Martin-like grid structure that is Skin (Randy King Size Wired) (2013) – that comprises no less than 2,448 white rectangles stuck to a wall. Imagine a Gerhard Richter grid painting as done by Robert Ryman and you are getting close to its impressively soothing impact.

Is there anything left from her stash of trash that might be used? Yes – with Pulmão (Lung) (1987), made out of 1,200 old packets, she creates a stack comprising of separate cellophane cigarette pack wrappers placed carefully in a Plexiglas box. Air currents waft these: hence the title of the work that knowingly references nicotine and the damage done…

This is a beautifully installed exhibition of work by the Brazilian artist. Rigour is applied thoroughly in the display of these constructions that reflects Leirner’s near Asperger-like repetitive gesturings. As with Gregor Hens’ writing we are given an elaborately generous exposition on the heaven and hell of addiction.

Jac Leirner: Add It Up, is at Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, until 22 October