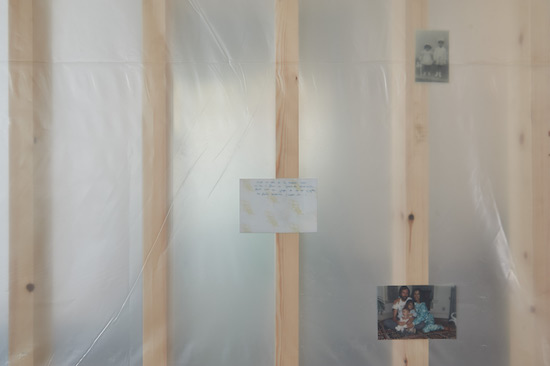

Residue, Tako Taal (2018), Grand Union (Photo credit: Patrick Dandy)

Inherited Premises is a show that explores our connection to time and place. At Birmingham’s Grand Union Gallery it brings together artists Rami George and Tako Taal to make new bodies of work. This two-person show is a reflection on personal and national narratives, shifting away from a singular perspective to reflect on the multiplicity of self-representations inherent in diasporic experience.

Present in the works shown is a sense of destabilisation and opacity, the summer sun is obscured by grey curtains and seating is provided to encourage the viewer to stay with the work and to give it thought and contemplation. Projected on either side of a hanging screen, both films utilise imagery that is both symbolic and amorphous to mediate questions of the genetic and experiential inheritance present within our bodies. While one film plays on one side, the other is dormant making space for interpretation. The exhibition is structured within the gallery as a conversation that addresses broader questions of national borders, conflict, imperialism, and folklore.

I spoke to the exhibition’s curator Seán Elder on the dynamics present within the works.

I wanted us to start with 1989 as a time that you reference in this exhibition as a point of curdling and shifting national identities. I’m curious about the impact of this era on the show.

Seán Elder: 1989 has always been a reference for Tako and I in previous lives, working and being together. It became an almost tongue-in-cheek way of talking about historically important events, as it was also the year that Tako was born.

The most visible icon of a reconstruction of existing borders, at least from a perspective embedded within Anglo-European culture, was the fall of the Berlin Wall. It was really interesting to research that within the context of the work that Tako and Rami have made. Particularly the Ta’if Agreement, which began the end of the civil wars in Lebanon. [It’s] similar to the Good Friday Agreement of Northern Ireland and Éire, in that it wasn’t a perfect end to it, but it did mark the beginning of the dismantling of these conflicts.

So it’s really interesting that this wall fell. We know the images of it – bricks being dismantled – and the idea of it – borders being dissolved. But this idea of 1989 kept cropping up, as it was also Rami’s year of birth, so it became this understanding of the many interpretations and relationships to these critical historical junctures, something more complex than a singular image.

Install view of Inherited Premises, Rami George and Tako Taal (2018) Grand Union (Photo credit: Patrick Dandy)

There’s a cross-reference here to Nicolas Bourriaud, who in his book Altermodern, refers to the fall of the Berlin Wall as an “emergence from glaciation”. Here he also references the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre, which took place in the same year, a curatorial point in which non-European artists break out from reductive modernist definitions of primitivism to be presented on an equal stage. In the events and screenings that have taken place with this exhibition you programmed Black Audio Film Collective’s film Handsworth Songs, a huge anchor for the representation of the black British experience in Birmingham. What connections are you articulating here?

In the context of the extended programme Rami, Tako, and I have had a lot of conversations about representation – particularly self-representation and the power and agency you have to do that. The autobiographical is a valuable mode in the current political situation we are living in. Handsworth Songs was a way for Birmingham to represent itself within the project. There’s a resurgence in referencing collective filmmaking, and the anti-racist, anti-sexist actions undertaken by Black Audio Film Collective seemed so relevant to contemporary practices. More widely, the programme became a way of thinking through different material ways of being – with (the notion of) respite anchoring a lot of the conversation we hosted by Marlene Smith and Ajamu, that touched on gender, sexuality and memory.

While I didn’t want to furnish the exhibition with an extended programme that was specifically tailored to a very regionalistic, cordoned-off treatment of these issues of identities and how we form them, there was definitely an importance for Birmingham to have a presence within this project. Even if Tako nor Rami nor myself are from, or are a product of, the city.

A felt narrative within the show is that identities are shifting things that don’t need to be fixed or can’t be set.

Both Rami and Tako have made works that could come very close to being singularly authored, autobiographies coming from completely their own mouths in their own voices. But instead, within their processes, they implemented a generosity in opening up the narratives to other forms of contribution and interpretation.

Rather than representing themselves as central figures, or conversely, focussing solely on the histories surrounding them, they’ve created works that complicate these positions. Rami’s work was very concerned with how the [Lebanese Civil] war “lingers in a diasporic body” – I think I’m quoting an exchange with him from memory here – and thus understanding how this civil war is a very material part of his connections to Lebanon and Beirut, through his Mother’s own history. And there’s this distance that occurs in the film, with a voice narrating over multiple images, with different authors and contributors.

Similarly, Tako, undertook a specific way of looking at histories through her birthmark. The birthmark’s scientific and cultural associations – particularly with her paternal homeland of The Gambia – has created this somewhat shifting, opaque representation of cultural and familial values. Both the artists’ works have a whole number of personal histories to them so there’s an importance for me to not misrepresent. But between both films, there is a definitely a sense that symbols, motifs, stand-ins, and other voices are present to point to multiple interpretations, understandings.

Detail of Untitled (before, during, after), Rami George (2018) Grand Union (Photo credit: Patrick Dandy)

In this show there’s also a space for two artists that becomes shared. You’re crossing a division in the gallery space. Tako has provided a platform for seating for both works. There’s a consideration as to how it gets experienced by the viewer.

Whilst we knew this was a two-person show and it wasn’t collaborative, we didn’t want the space to be divided by one big partition with two bodies of work severed from each other. It’s really evident that there’s an exchange, but the difference of the works is evident. So the floating screen has really acted to hold space for both artists. Initially, it came about because it was agreed that we wanted sound aloud in the space.

It was about sound and how sound occupied the space, so the solution became to have sound playing on one side of the space and then the other to accompany the film works, as the major commissions in the show. Translating that into the exhibition itself has created spaces that lie dormant, acting as a respite while the other film plays on the other side of the screen. It’s become a conversational structure.

That sense of conversation is really present. Within the work you’ve got these elements – this connection to family, geography, borders, space, what’s contested and what isn’t. How much of this has emerged through seeing the work together?

These complexities, the similarities and differences – the exhibition consolidated them but also completely destabilised my understanding of it. I’m just thinking about the ways that both Rami and Tako have both looked at their family histories to represent these conversational, layered narratives, but still open up opportunity for viewership.

Untitled (the wars in Lebanon), HD Video, 12 mins, Rami George* and Untitled (before, during, after), Rami George (2018) Grand Union (Photo Credit: Patrick Dandy)

There’s a sense that the image is not certain. You’ve got a presentation of photographs from Rami where there’s this familial archival footage that’s placed in ways that makes it unviewable, so there’s this sense of slippage. At the same time you’ve got this slide from Tako, that’s continuously projected each day and is discolouring. These are really intriguing works in relation to the films, as they have the implication of images not being certain.

There’s an opacity to the images. Within this exhibition space, you can see that opacity in physical form with these photographs which are from Rami’s family albums. The structures have been built to support, show, display them, although it isn’t quite clear because they’re obscured but somewhat revealed. You have to look closely at the photographs to make the connections and map them out, as well as seeing the languages written on the back of them: French, Arabic, English. So even understanding the relationship between those three languages, which make their home in Lebanon at different times and with different power relationships, takes work and viewership

Then with Tako’s image of these oranges – which are a very common sight to see. Dried out husks which are drunk rather than eaten in the Gambia, then tossed aside and become a way-marker. An identification that someone has taken that path previously. The slide, which has this image of the orange displayed, is becoming more difficult to discern. Just as in Tako’s film, she was using these oranges and amorphous shapes on slides or glass as a stand-in for the titular birthmark of her film Halo Nevus.

There’s a fascinating curiosity that goes back and forth in the space, the breaks within it. There’s a conversation that happens with pauses, not a consistent hectoring. A sense of listening.

Both the works, though they do it in different ways, are highly personal. The historical happenings that they are discussing, whether it’s legacies of colonialism or someone’s coming into contact with civil war or sectarian conflict, there need to be pauses for that to be digested within the space. For someone to understand their position in relation to it in the gallery. I think there’s a value in that slowness of the exhibition, taking time for both the works which have done a really beautiful job of leaving themselves open to multiple interpretations. In a way, this is dependent on these breaks and blank spaces. These moments of respite.

Inherited Premises, a two-person show by Rami George and Tako Taal, is showing at Grand Union, Birmingham, until 3 August 2018