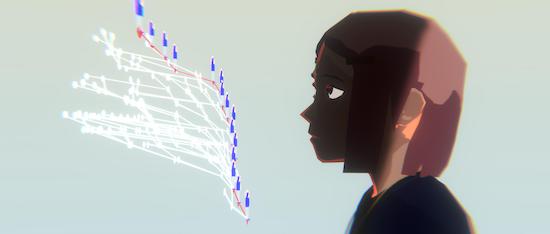

Ian Cheng, Life After BOB: The Chalice Study (still), 2021, Real-time live animation, colour, sound, 48 mins. Commissioned by LAS (Light Art Space), The Shed and Luma Arles. Courtesy of the artist

Ian Cheng was one of the first artists working with artificial intelligence to break through into the contemporary art world while most artists engaged in the field were still operating mainly in the tech world. Cheng’s Emissaries (2012) trilogy, a series of AI-powered worlds, played out on large, painting-sized screens, explored the idea of worlding and worldbuilding which still lies at the core of his practice. After Emissaries came BOB (Bag of Beliefs), an ‘AI creature’ which evolves each time it is exhibited. Viewers can interact with BOB and experience how it changes over time.

Now, Life After BOB is an immersive experience installed in Halle am Berghain, the gallery space inside the legendary Berlin nightclub. It is a multifaceted exhibition with an animated film at the heart of it. We are taken on a journey which starts with the first half of an I Ching reading, giving each attendee a personal trait to overcome. How they might overcome it is revealed at the end of the show. Then we entered a light space, the enormous halle of the club itself, a former factory, which still bears the scars of its ravey past. We waded through what felt like a pool of water, a trick of the light that cuts through the space before a sun flashes repeatedly through the dark and then guiding us down to the cinema space for a screening of Life After BOB: The Chalice Study, the first in an eight-part series.

The story follows ten-year-old Chalice, the daughter of Dr Wong, who has implanted his daughter with a Destiny BOB AI which takes over her existence from age ten to twenty. Cheng’s work poses the question ‘what if an AI could live your life better than you?’ The plot follows just what Chalice’s Destiny BOB does with her life before she gets it back, ten years after giving it up.

“The idea for the script came from this book by Eric Berne, a psychiatrist from the 70s, called What Do You Say After You Say Hello? It’s all about the idea of life scripts,” Cheng told me. “He was inspired by Carl Jung. Everyone has a script. We might not know what it is. You might want to rewrite it because it could be a tragic one, but we are all barrelling toward it. In his psychiatric work, he found that people – even if they really didn’t want to – since so many life decisions are too immense to make, they just ended up defaulting to the script.”

Burns discovered through his research that all people needed was permission to not follow the path that life seemed to have in store for them. In the film, Chalice has to fight for autonomy in her own existence and is then forced to ask herself the question: is the AI doing it better than I could?

Following the film, we are invited to engage in ‘Worldwatching’, meaning we can pause the film, enter each scene and explore the characters and symbols within it. The film is built in with the Unity game engine which means the film streams in real time and can be edited in real time as it plays. Inspired in part by the artists’ daughter’s desire to expand on her favourite bedtime stories and ‘go in’ to each page, we can take a dive into the story at any point, via a mobile phone. Cheng offers the experience of interacting with Chalice’s story on a deeper level, controlling the stop, the start, and how much detail we go into.

The experience takes world-building to another level as we can step into the film and immerse ourselves further into it, demanding that we look at what AI in our lives means. In raising the question if a machine can do something better than a human, should the human just stand aside? We are forced to consider what living ‘better’ actually is. Is it maximising an existence or is it less tangible than that, is it about a more nuanced inner truth? Also, perhaps most importantly, who decides?

“It’s an existential journey,” says Cheng. “Maybe there’s something hopeful about it, or something that inspires people to come alive to their own potential.”

The exhibition ends with an NFT that concludes the I Ching reading combined with an astrological reading you receive at the start, offering you the chance to alter your path if you choose.

“The hope is that there’s something redemptive about it that, even if this is your life script, and this is something ugly that you don’t like about yourself, it’s like a provocation – I know what that means for myself,” Cheng elaborates. “If an art exhibition can push the needle on that a little bit for a person. Lovely. I love that art can change people in small ways.”

The next seven episodes of Life After BOB will explore the other characters in the film, from Chalice’s father, Dr Wong, to her jilted lover, Alan, who is up next, in episode two.

“He fell in love with Chalice. It’s alluded to that they had some relationship in the intervening years, but then he got kind of side-lined by all the other events in the film.” I really want to write a story about him.”

Cheng admits that his daughter, Eden, was a big influence on Chalice and says that Alan and the conundrum of raising boys in the modern age will factor in the next part of this work.

“I wrote about what scared me – becoming a father and this idea that Dr Wong conflates his daughter in his work, and I had this fear. I have a son now and I’d like to look at how you raise a boy. It’s quite a sensitive topic. It’s something I want to explore by making it, by writing it. I don’t know the answer.”

Life After Bob By Ian Cheng, presented by LAS, is at Halle am Berghain until 6 November