Inflatable art is incredible – its materiality and physical presence bear an ultimate contradiction. When faced with an inflatable sculpture we are met with scale, noise and magnitude, yet deep within exists a quiet suspended violence, a ticking time bomb. The true fragile nature of an inflatable is unshakeable. One wrong move and the party’s over.

An inflatable is extremely playful in nature, drawing upon childhood clichés: bouncy castles, helium balloons, kids birthday parties. However, the sleek shininess of the surface area bears with it something more sinister and fetishistic – a perfect second-skin. I’m thinking about blow up sex dolls, Berlin latex fetish parties, and to get real niche: The Rover, from 60s sci-fi cult TV show, The Prisoner. The Rover is a big white balloon that would chase, incapacitate and sometimes kill anyone trying to escape ‘The Village’ a fictional coastal town. Brilliantly parodied here in The Simpsons.

Inflatables are an overwhelming, all-encompassing medium whilst being 99% air – their only mass is that of their wafer thin latex skin. It’s one big charade. I think this is what I find most appealing: how they can go from all to nothing with a single pin prick. A truly transient, unpredictable, slightly terrifying way to make work – which goes along nicely with the Bad Art ethos. (Not exactly sure what that is yet, but something along the lines of traumatising-slash-exciting the public with art.)

In its critique, Hot Air is literally mostly empty space – a satire of the vacuousness of much of the contemporary the art world. The amount of semi-incomprehensible, pseudo-intellectual talk at some of these art openings… it’s all hot air. We’re all guilty of it, but it’s good to be aware of the bullshit that comes along with working in the creative industry and point a big inflatable finger at it.

I wanted to put on a show that re-instated our physicality, a reaction to watching my own identity and ego slowly slip into the vacuum of virtual reality while ‘real-life’ restrictions increased in the past year. Hot Air is going to be enormous in scale and extremely loud, the space is going to be an immersive, demanding experience – and probably pretty unpleasant. I felt like we needed something big, bold and colourful to make us feel something… ANYTHING after all the hours we’ve spent staring at our bedroom walls for the last while.

Most importantly, I felt that an international art community was needed now more than ever. I’m really proud of this show because we’ve strung together a line up from all around the world: Russia, America, Philippines, UK, Germany, Austria etc etc. Organising an international show during Covid has killed off a part of me that I don’t think I’ll ever get back, but I felt like we just desperately needed some connectivity and to reunite with the rest of the world (also inflatables are cheap to ship and you don’t get a lot of VAT hassle at the post office). Anna Choutova

Bruce Asbestos

I’ve been thinking about the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City. I love how the whole thing that people go and see is the art itself. It’s not like the Olympics or other big events where art is attached as a secondary thing, and deemed useful to have around.It’s the thing people want to see: big sculptural floating cartoon characters – almost like a carnival for sculptural objects.

We find these things mesmerising; these inhaling, exhaling monsters, floating through the sky. It connects us to a pre-scientific history where most of the mechanics of life, death and the cosmos are pure mystery. It revives those feelings of uncertainty and wonder – a kind of PVC Yeti, UFO, Bigfoot or Loch Ness Monster.

It allows us to escape our technical understanding of almost everything on earth. We might understand how a balloon rises, but a huge object floating on air is counter-intuitive. We cannot believe our eyes!

Nancy Davidson

Like architecture, the history of sculpture is weighted by permanence, monumentality, and memory. In the early 90s, I was reading Mikhail Bakhtin and thinking about the grotesque and the carnivalesque. I was intrigued with the humour and chaos of these spaces and the importance of the viewer. I wanted to work larger and manage the weight of the sculpture myself. In a eureka moment, I sent for a weather balloon. The moment I blew it up, I immediately knew it was the perfect material: ephemeral, erotic, funny, absurd, and huge. A body with flesh and importantly, a body of parts: bulbous parts that all bodies have. The bulging “flesh” subverts common stereotypes: “big is beautiful” riffs on minimalism’s “less is more”. The inflation nozzles are ambiguous, phallic, yet receptive in function.

Every aspect of the inflatable carries its opposite. They behave like living organisms by breathing but are not alive. They swell to amazing forms only to deflate into a shriveled pile. During WWII, the British used inflatable tanks, a “ghost army” unit fooling the Germans while inflatable sex toys were popular items.

The roots of my influence begin with the attitude toward new materials found in the art of the 60s, and the exhilaration of something-out-of-nothing propels me forward. My work reaches for the regenerative pleasure of touch, the fragility of creation, and the spectacle of the body as form. Inflatables evoke human anatomy and the human condition: the struggle with gravity, the flimsy materials, the delicate stasis between inflation and contraction.

Lucy Gregory

There’s a playful but performative battle when exhibiting my inflatable sculptures – trying to keep the air from escaping! Often these pieces are memorialised as photographs, which conceal the transient and fragile nature of their architecture. They’re tricksters; like creatures that rustle and sway, responding to chance effects or subtle environmental changes: a draught of cold air or the vibrations from the Underground, they flop and sag as time passes.

Having battled to keep these misbehaving shapes upright, taking them down is another fight to get the remaining air out. Often passers-by participate in helping: it becomes a spontaneous, cathartic effort of belly flopping and squeezing the bloated plastic in a large group hug as the creature takes its last long exhale. This narrative is nostalgic, taking you back to playground games and running under the rainbow parachute as the sun casts a red glow into the polyester dome.

The sculpture is scrunched back into a suitcase and wheeled through London. This enormous, garish mass is encased like a chameleon to blend with the fabric of the city, like the unknown contents of a magician’s bag. Riding the Piccadilly Line, the trickster in me wonders what would happen if I just inflated it right here…

Kalman Pool

Sealed inflatable sculpture is nomadic, compressing and deploying, a container of emptiness. I am fascinated by the unpredictability and aliveness embodied within the inflatable’s material nature, where fragility manifests ephemerality, care creates intimacy; a still yet moving agency. From the Ghost Army in WWII to contemporary applications, the inflatable sculpture functioned as a visible phantasm, a simulacrum—portraying a sustainable and low-cost sculptural future.

Sasha Frovola

I love to work with air as medium, firstly, because I am attracted by the unique biomorphic plastic, the softness of the lines that the air gives. I’m interested in the principle of shaping, which is possible with the help of air only. The form swells, stretches, it turns round, it has smooth bends. This effect is hard to achieve with carving from marble or with sculpting from plaster. The air together with the material create the form and I am fascinated by this co-creation – you never know how the pattern will swell, you try to figure it out, and this is a very interesting game-like process.

I like the fragility of inflatable objects. It seems to me that they create the feeling of living beings, the shape is soft and warm, filled with air like us, and the smoothness of the material resembles skin. I create my sculptures from air, wrapping it in a thin latex membrane, giving shapeless air a shape, texture, density. My forms are fantasies that can deflate, disappear, dissipate at any moment like a soap bubble. Only a thin latex cover of 0.33 mm keeps them from disappearing.

I work with different materials and techniques, but I am known mainly because I work with latex. Latex is my main and most favourite material. I use it for creating costumes, sculptures and large-scale installations. I have been working with latex since 2008.

Latex is very sensitive and difficult to work with. It is afraid of UV rays and time. But I like its ephemerality, airiness, softness, and smoothness. Latex sculptures seem alive.

Another important thing for me is the collision of the naive context and the sexual context, which latex brings. This conflict has a disturbing influence on the viewer, who does not understand how to perceive it, and begins to argue with himself about what he sees now. This is what I want to achieve – to engage the viewer emotionally, to fascinate, hypnotise and to excite.

Rosalynn Gingerich

Inflatables connect us to our ethereal imaginings. Their air-filled membranes are an extension of the body, serving as a platform to explore memory and its relation to the body. Inflatables have a unique ability to exist outside traditional artworld structures, making them accessible to a broader audience while providing liberation from formal gallery constraints. Large, architectural inflatables move art into the open, presenting it directly to the public, while claiming landscape and viewers as part of its vocabulary. Transforming any location that they engage, large inflatables ultimately require the viewer to be part of the work itself, blurring the perception of space, and prompting a unique emotional response in each participant. <

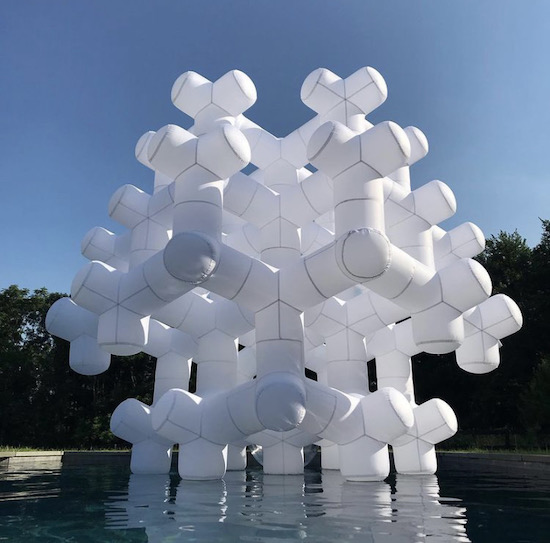

Pneuhaus

Inflatables are an incredible medium for many reasons. First of all, they are cheap, most of the structure is free and all around us. Second is they are a relatively new medium to work in. It’s only been since the mid-1900s that the technology was invented to make plastic membranes possible. Third is the type of forms are totally new and unique to anything else in the built environment. Architects and designers who design with organic forms usually translate it to bricks, wood, metal, or other flat stock. But with inflatables, organic forms are the norm, flexibility is a given, and curves are everywhere! For us, there is so much to be discovered in the inflatable medium in terms of craft, types of structure, and forms.

Bad Art presents… Hot Air is at Manor Place Warehouse, London SE17, until 11 July