The Serpentine Gallery is no stranger to the spiritual.

Two years ago this summer they staged performance art shaman Marina Abramovic’s ambitious and sort-of underwhelming 512 Hours, a protracted exercise in trust in which Abramovic invited the audience to participate in an agonizingly drawn-out ritualistic performance.

At the beginning of March the Serpentine reopened its doors to the mystical with an exhibition of paintings by early 20th century Swedish artist Hilma af Klint.

It’s a big exhibition, packed with paintings. The bulk of them are taken from her decade-long project, Paintings for the Temple. It was started as an unusual sort of commission – given to her by a spirit she contacted with a group of likeminded female artists who collectively called themselves The Five. Together they conducted séances in an attempt to reach beings from beyond this plane and reconcile the material world they occupied with the occult spiritual world they believed firmly in.

Taxonomically, the project is complex. Paintings for the Temple comprises 193 paintings, almost half of which are on display at the Serpentine. The paintings are subdivided into varying series and systems, individually related and each contiguously connected to the others. All, in some respect, riff on similar themes. Using a large and unique array of signs and systems of meaning, af Klint attempted to reconcile dualities in pursuit of a fundamental unity she perceived as having existed at some point in the distant past.

The literality with which the paintings depict these dualisms varies from series to series. In some, like The Swan, they are explicit. A painting here shows two swans, poised. The canvas is bisected horizontally across the centre, black above and white below, with the birds, also black and white, occupying corresponding positions on opposite backgrounds. Their beaks touch across the divide, likewise the tip of one wing. The positioning of two opposites, interfacing across their apartness, isn’t complex in its description of the resolution of a divided whole.

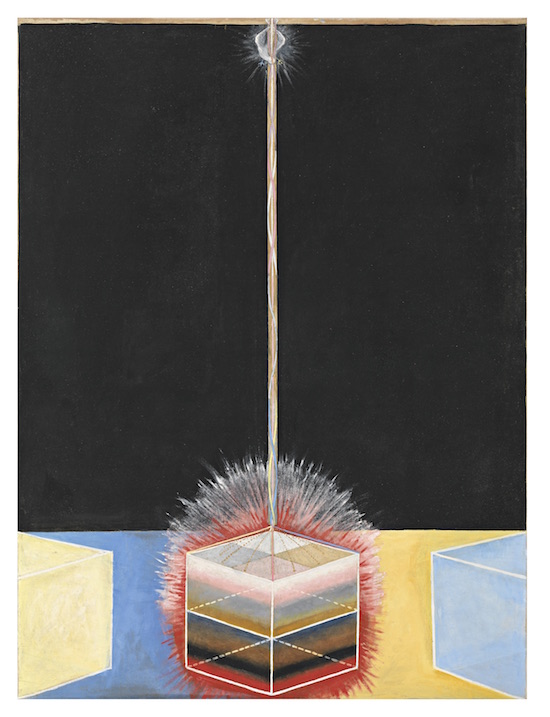

Beside this one hangs something more purely abstract, although its description of binary poles is the same. Where the swans form a point of contact with one another is evocative of Escher’s repeat patterns, the cubes that hang suspended in the void of this one are more reminiscent of Malevich. But whilst his geometric forms express tension; af Klint’s, suspended against a white background, almost appearing to orbit or pass each other like cold alien objects in an unknowable plane, hang still.

As with the painting of the swans, the canvas is bisected horizontally. Like the swans, the upper pane is black and the lower white. In place of birds, though, are these cubes rotated on different axes, suspended in concentric circles around a central cube. The whole thing emits beams, blue above, yellow below. The contact between the two halves is less unified, but it manifests the same symmetry and the same message – of a divided whole comprised of two halves that are the same, only different.

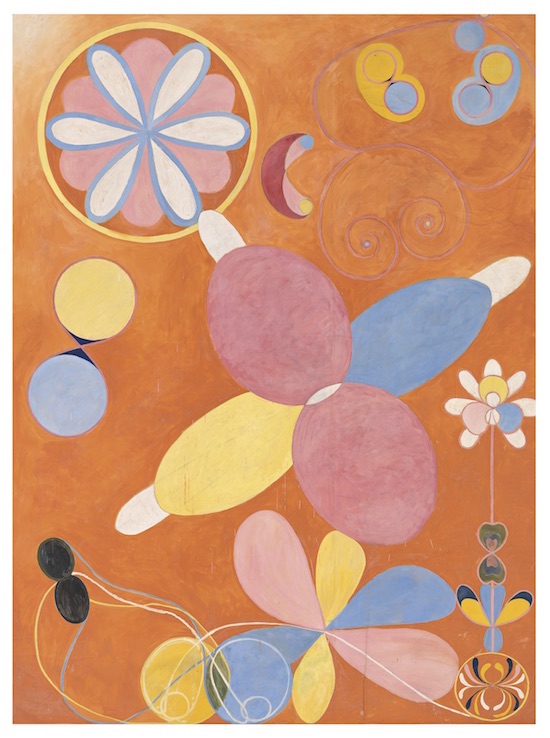

Hilma af Klint, The Ten Largest, No. 3 Youth, Group IV, 1907, Tempera on paper mounted on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Elsewhere, massive paintings hang; three metres tall, there are eight here from another separate series, elegantly called The Ten Largest. These hang in the central room of the gallery, and are, for my money, the best in the show. Here symmetry is foregone in favour of a more latent and less bombastic, but no less developed, symbolism. The paintings narrate a lifespan, from youth to old age, in joyful and colourful abstract forms.

The signs are drawn from across the natural world, on macro and micro scales. Plant cells are present alongside ova and sperm, petals and ammonites. They’re compositionally harmonic – and they’re also distinctly psychedelic. It’s in here that af Klint’s position as a painter in the 20th century feels most extraordinary.

She is remarkable because her experiments in abstraction predate its consensus-opinion start of around 1911 by half a decade. Her explorations and her corresponding development of a sophisticated and rich visual language began in 1906 – five years before Wassily Kandinsky’s. Whilst her practice shares similarities with the likes of Malevich and Kandinsky – other artists whose work is viewed as essential in its pioneering exploration into abstraction (and by extension, as formative in the development of modernism) – her name is strikingly absent from the conventional narratives of 20th century art history. Indeed, she garners only two mentions on the Wikipedia page for abstract art.

Her paintings, like Kandinsky’s and a number of other early modernist painters, were informed by the writings of Madame Blavatsky, founder of the Theosophical Society. Theosophy as developed by Blavatsky can be viewed as a kind of post-gnostic mish-mash spiritual philosophy of everything, mixed together in an attempt to find some sort of unified worldview (both physical and meta-). It attempts to mediate between science, nature and spirituality – a not unreasonable ambition in the wake of the totally game-changing scientific discoveries being made in the 19th century.

The relationships between abstraction, modernist progress and mystical esoterica are themselves illuminating. Logical connections between people faced with unprecedented change and a recalibration of faith – from Gnostic spirituality to something that places vastly more significance on matter and the material world – explain in a general way the environment in which early abstractionists were working.

Whilst the underlying social, spiritual and scientific environment of Europe in that time might have informed artists working along broadly similar early avant-garde lines, af Klint’s development and subsequent legacy took a very different path to those credited with pioneering abstraction.

Hilma af Klint, The Dove, No. 3, Group IX/UW, 1915, Oil on canvas, Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

This exhibition is heavily concerned with the artist’s mythology, and with good reason. Whilst the paintings in the exhibition do actually vary in quality (a series that incorporates simultaneously abstract and representational elements, including one in which a nude man and woman reach for a chalice from either side of a shared circle – fringed with the letters "EVO LUT ION EN" – is especially iffy) they occupy a unique liminal position in both the circumstances of their production and, subsequently, in the modernist canon.

Af Klint was no outsider artist; she came from a formal background, trained to paint landscapes and portraiture and deriving a living from doing so. But these paintings were private – produced in semi-isolation and never exhibited during her lifetime.

In fact, their exhibition was subject to a 20-year moratorium after her death, imposed in the conditions of her will, for reasons speculated on in the exhibition catalogue. She was heavily influenced by the spiritual guru Rudolf Steiner, who apparently during a studio visit advised her that the world was 50 years away from being ready to see the paintings – although she also died in 1944, at which time the cultural atmosphere in Europe may not have felt particularly sympathetic to an artist who freely experimented with the esoteric and mystical, for obvious reasons.

Her artistic experiments were inspired both by the aforementioned theosophical mystical discourses and her spiritual voyaging with The Five. Her training precludes her classification as outsider, but the isolation of her work precluded the possibility of her art exerting influence – even if her paintings were astonishingly prescient and before-their-time. However they are more significant than curios, and they also seem to cast a shadow longer than is suggested by the apparent dead-end of their first being exhibited in the mid-eighties – by which time the moment when they could have any really significant, game-changing impact on the development of art had surely passed.

In this collection of highly unusual, variable but quite potent paintings we see the development of a highly sophisticated language of meaning-making. I’d argue that the language is abstract, but in its abstraction representational. These paintings don’t explore the limits of painting, or of art, or of feeling, but rather use complicated signifiers – from letters to colour to symbols, each with their own autonomous meaning beyond the context of her narrative – to describe a spiritual world that was as real to her as our physical one, at a time when scientific and cultural developments were blurring the boundaries between the two in a way that they had never been before and haven’t been since.

Whilst her isolation necessarily marginalises her in the history of art, the spirituality she was immersed in has a distinct legacy, running through the counter-cultural movements of the sixties, to the new-age movements of the seventies, into the self-help movements of neoliberalism. Her paintings offer an iconic and in some instances startlingly prescient illustrated guide to the genesis of contemporary spirituality, as well as a fascinating glimpse beyond and around the curtain of received wisdom that has so far dictated the narrative of 20th century art.

Hilma Af Klint – Painting The Unseen is at the Serpentine until 15 May