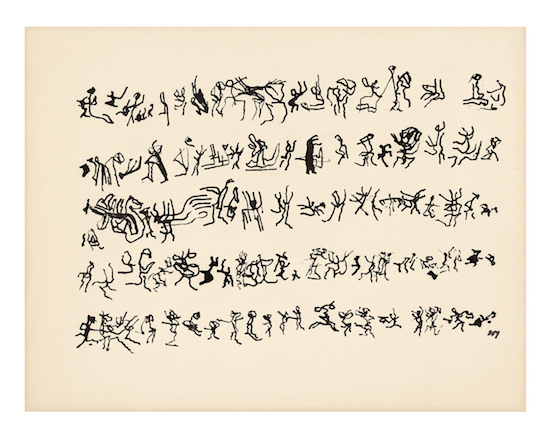

Henri Michaux, Untitled, 1963 India ink on paper 322 x 417 mm Private collection © Archives Henri Michaux, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2018 Photo: Jean-Louis Losi

Henri Michaux was a shy, intensely private man and he was painfully socially inhibited. An anecdote told by the director of the Fondation Michaux, in Paris, where the Belgian writer, poet and experimental visual artist lived for most of his adult life, relates an awkward dinner with Georges Perec. The two shy men squirmed in near silence for the entire meal. And since eating in public was also anxiety-inducing for the quiet Belgian, he ate while covering his mouth.

There is something self-effacing too that we note in portraits of the artist, in the few photographs displayed in Guggenheim Bilbao’s survey. A photographer astutely captures his wish for invisibility. One contact sheet shows a series of images in which the artist’s shadow is looming in the centre of the frame, his profile sneaking in from the edges. And when his full profile does come into view it’s heavily veiled by shadows. In one image only his hunched back is visible in the bottom corner of a white backdrop. But rather than conveying a sense of discomfort at being the subject of the probing lens the images capture the teasing playfulness of the artist, which is often so evident in Michaux’s poetry.

The survey features 200 drawings, paintings and works on paper, with many often on sheets torn from notepads. There is a sense that much of his output was ephemera, an attempt to capture a fleeting mental sensation but with little consideration for the work’s afterlife. The majority are untitled and left undated, with many more still being catalogued almost thirty-four years after his death, aged eighty-five. His drawings and paintings were something to escape into, their quick, spontaneous labour a relief from his life as a writer.

Michaux was influenced by Paul Klee and Max Ernst and by the Surrealist’s exploration of chance, though he was never a paid-up Surrealist. He is sometimes called a neo-Surrealist, though the distinction between that and Surrealism isn’t entirely, if at all, clear. He had no interest in the automatic drawing or writing pursued by many of the associates and affiliates of the movement, and André Breton, its authoritarian theorist, disregarded Michaux’s pursuits as outside Surrealism’s intellectual concerns, as he had Michaux’s fellow Belgian René Magritte, whom Breton had dismissed from the movement.

The exhibition is chronological, though its chronology is disrupted by being divided into three thematic groups: the human figure; the alphabet; and the altered psyche. These are broad groupings and in practice rather fluid in terms of Michaux’s vast output, so that it feels like you’re rushing back and forth through spans of time without much of a sense of a coherent journey.

Henri Michaux, Untitled, 1938, Watercolor and gouache on black paper, 230 x 305 mm, Private collection © Archives Henri Michaux, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2018 Photo: Jean-Louis Losi

The curator, Manuel Cirauqui, says that he was interested in gathering lesser-known works, though since Michaux is a relatively little-known mid-century artist whose work is rarely shown in extensive retrospectives such as this, one might ask why. This result produces a kind of wallpaper effect, with few works arresting the gaze, until you get to the final room. Here are some of his extraordinary, meticulously detailed drawings made under the influence of mescaline and hashish for which he is best known, in terms of his visual output.

Watercolours from the 30s and 40s contain an element of chance, but only in so much as he took his cue from an initial splash of paint from which his otherwise premeditated forms grew: forms that are whimsical or monstrous, fragmentary and elusive. He was interested in Chinese calligraphy, hieroglyphs, pictograms and musical notation (he was fascinated by music and musical instruments from Asia and Central America and examples from his collection are displayed, as are a selection from his ‘ethnographic’ sculpture collection at the beginning of the exhibition). His experiments in asemic writing are studied and precise, and you imagine he might have made a master calligrapher in the court of some ancient emperor.

Elsewhere, in some of the only works bigger than an A4 sheet, are his black ink paintings. These are fluid and spiky, with mutant forms that coalesce and fragment as if these schematic human figures are melting into each other or dividing like cells; or else they are like fat quotation marks whose animated symbols are smudged or tumbling across the page. Or perhaps they are like vibrating fissures on the earth’s surface or the rushing waves of the sea. They hint at the microscopic and the cosmic, and they are occasionally sinister and starkly beautiful.

His interest in other cultures, in Eastern philosophy and spiritual practices, as well as, naturally, in Freud and the subconscious, led Michaux to push beyond the parameters of everyday experiences to ‘the other side’, as the exhibition is titled. But far from enacting the role of an early counter-culture figure, it wasn’t until he was fifty-seven that he took any mild-altering substance, and then only, at least at first, under medical observation. The meticulous drawings he made under the influence are incredibly precise and fine, like delicate silverpoint etchings, and obsessively detailed, with a wild, gothicky aesthetic. They are among his finest pieces.

Henri Michaux: The Other Side at Guggenheim Bilbao until 2 May, 2018