ADAM MCEWEN, Untitled, 2020. Flashe and spray paint on paper

11 1/4 x 15 3/4 in, 28.6 x 40 cm © Adam McEwen. Photo: Robert McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian

Photography meant haunting, at least to Roland Barthes. To Barthes, the greatness of the photographic image stemmed from a transgression of the bounds of biological memory. The mnestic image, after all, is shaky, mutable, wholly dependent on our decaying sacks of flesh. A photo isn’t: you might tear it apart or burn it, but while it’s there it depicts clearly and unmistakeably a presence that is no more. The palpable unexistence of a ghost, “the unreality of the thing represented”. Barthes wrote, “The image, says phenomenology, is an object-as-nothing. Now, in the Photograph, what I posit is not only the absence of the object; it is also, by one and the same movement, on equal terms, the fact that this object has indeed existed and that it has been there where I see it. Here is where the madness is […] a mad image, chafed by reality”.

Barthes was also convinced that society was terrified of photography precisely because of the mad, elusive presence it brought forth. And society, he went on, employed a couple of tactics to contain and neuter these haunting images: by turning photography into an art or a banality. The latter is a reasonable insight. History has proven him right and photography is a banal fact of life nowadays. The former, though, is where Barthes loses me. When he claims that, unlike photography, “no art is mad” he seems to wilfully forget just how much art, any art, rests on precisely the sort of maddening presence he endows photos with: things lost and burned on a canvas or a piece of paper or some other material.

Effective art is a question of palpable hauntings, separated by the peculiar technical demands of each specific field. Someone’s or something’s there and then it’s not, and therefore there’s a painting or a book or a sculpture that bears their mark. Our galleries and libraries are monuments to inconsolable mourning.

I patted myself on the back as soon as I walked into the Haunted Realism exhibition at the Gagosian in London: considering the works exposed there, Roland Barthes was clearly on the wrong side of this wholly imaginary argument.

Haunted Realism, installation view, 2022 © Urs Fischer; © Meleko Mokgosi; © Neil Jenney. Photo: Lucy Dawkins. Courtesy Gagosian

As the name readily gives away, the exhibition is dedicated to all those things that haunt our present world – the ghosts we buried, forgot, or foreclosed. It goes about its exploration through a variety of mediums: painting, photography, sculpture, with a few hybrids that fall in between these categories. What unifies all the works is a certain sense of madness, disquiet. There’s an underlying creepiness that stalks the halls of Haunted Realism. All of the art hanging on the walls or occupying some corner of the gallery shares that same unreal presence that Barthes wanted to banish from most of the arts. Their power stems from an unnameable dread looming over it.

The main conceptual inspiration of the exhibition is Mark Fisher’s infamous hauntology (freely adapted from Jacques Derrida) and his work on our capitalist temporality. His name appears on every document accompanying Haunted Realism and his ideas are used to serve as an introductory theoretical framework for all the works hosted at the Gagosian. The gist of Fisher’s ideas is this: capitalism is a stagnating system, on an economic level, surely, but also an aesthetic one. We cannot even begin to fathom anything beyond capitalism, let alone something better. We are currently in a sort of recession of the mind. Because of this impasse, most of contemporary art nostalgically claws to the hopes and dreams of a past generation that now haunt us as the ghosts of lost futures.

The spectres of a world which could be free, as Marcuse once put it. Haunted Realism takes up this dismal historical conjunction as a challenge: summon these lost futures and exorcise them through works that actively engage in our collective haunting.

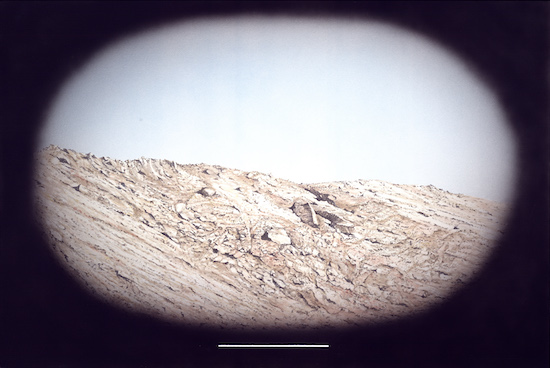

ED RUSCHA, Spied Upon Scene, 2019, Acrylic on museum board, 40 1/8 x 60 in, 101.9 x 152.4 cm © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy Gagosian

All of this theory surely gives the audience a nice way to psychologically prepare themselves for the creepiness they’re about to experience once they step foot into the exhibition. And it is true that most of the art in Haunted Realism wrestles with some ghost, something-that-could-have-been but got lost in the drudgery of this world. But I was also quite glad to discover just how absent the airy conceptuality of it all was from the actual exhibition. The walls of the gallery are quite barren and no further hauntological digression is brought up in the any of the rooms there. The works stick out on their own, so to speak, without philosophical crutches. The creeps they’ll give the viewer are a rather physical experience that would happen regardless of any previous engagement with Fisher’s writing.

There’s a certain brutality to the way the idea of our shared lost future is tackled in Haunted Realism and precisely for this immediacy the exhibition knots the collective, political nature of Fisher’s analysis to a more direct, existential dimension. It’s a raw one-on-one experience with grief, loneliness, and despair that aims straight at the guts. The various lost futures conjured throughout are left to speak for themselves and the result is extremely effective – even downright unsettling.

There are a few micro-trends that run throughout the overall exhibition: a few works, for example, openly recall the startling dreamworlds of surrealism, albeit in a darkened, gothic fashion. But the tendency that struck me the most was the one I’d call, to be polite about it, scatological. There’s a good handful of pieces – Jenny Saville’s, Ed Ruscha’s and Richard Prince’s, for example – that openly play with the idea of waste and trash and dirt to depict our lost futures – an idea quite brilliant in its viscerality.

There’s this subliminal equation that runs through a good chunk of Haunted Realism: our discarded dreams of a better life are represented with blood-stained mattresses, nasty polaroids, dirty tiles. This, again, gives a revolting physicality to very airy critiques of our capitalist imagination, shaking it with a flood of things we quite literally shat or bled out along the way. A tough sort of collective psychoanalysis indeed.

As I left the exhibition, I descended in the metro station to go wherever I had to go. An old Vampire Weekend song was blaring in this massive non-place. On my way down I felt furiously nostalgic for another world.

Haunted Realism is at the Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, London, until 26 August