“In one hundred years of film, there have probably been more prison gates than factory gates,” says Harun Farocki, narrating his Workers Leaving the Factory (1995). This documentary opens Scotland’s first major retrospective of his work, at the Cooper Gallery at the University of Dundee, putting five shorter films alongside the 90-minute, ten-channel installation Labour in a Single Shot (2012–14), made with Antje Ehmann, at the heart of the exhibition.

Workers Leaving the Factory goes back to what is often called the first motion picture: the 45-second La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon, shot by Louis Lumière at the photographic factory owned by him and brother Auguste and first shown in March 1895. This narrative – contested, as both Louis Le Prince and Thomas Edison shot moving pictures a few years earlier – puts workers, and the factory, at the core of a history in which the Lumières pioneered documentary and magician Georges Méliès invented the more escapist feature film.

To some extent, this is a false dichotomy, as one of Méliès’ most important works, L’Affaire Dreyfus (1899), blurred this distinction by reconstructing crucial tableaux from the French antisemitism scandal to form a historical record. An analogous impulse is at play in Farocki’s film, which, unlike Lumière’s, put ‘workers’ in its title. Here, scenes from feature films – by D. W. Griffith, Fritz Lang, Pier Paolo Pasolini and others – are used as documentary evidence for the rise and fall in importance of industrial labour, declining after the unionised struggles of the 1960s and 1970s.

Farocki is an intensely serious filmmaker, but Workers Leaving the Factory has elements of wry humour, with his voiceover framing Chaplin’s confrontation with police outside the gates in Modern Times (1936) as a matter of “personal honour” in a dry response to the Little Tramp’s clowning. Mostly, though, Farocki asks why film – feature or documentary – has been so reluctant to engage with processes of labour, mostly functioning as escapism from the things that occupy most of our time, even when it is dealing with traumatic subjects.

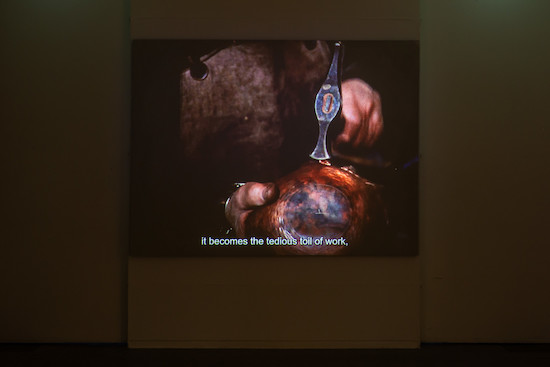

Antje Ehmann and Harun Farocki with participants Labour in a Single Shot, 2011–2014 Ten channel video, colour, sound, 90 minutes (approx). Installation view. Courtesy Cooper Gallery, DJCAD. Photo by Sally Jubb.

Labour in a Single Shot is the most ambitious attempt to redress this imbalance, and occupies the largest space in the Cooper Gallery. Between 2012 and 2014 – when Farocki died – the filmmakers ran workshops with participants across the world to produce one or two-minute videos of people working, taken in a single shot with a static, panning or travelling camera. Here, five or six shots from ten cities are presented on five sets of back-to-back screens, giving an insight into working conditions in Bangalore, Buenos Aires, Cairo, Hangzhou, Mexico City and elsewhere. With them all looping simultaneously, they produce a cacophony of noise that evokes a world of work; on closer inspection, and as per Ehmann and Farocki’s directions for their contributors, they capture different types of labour in their various locations, with names of workers and titles such as ‘Garment’ or ‘How to pick corn’.

The short durations feel like a callback to the Lumières, whose films were the length of a single reel. Some capture dialogue, where it is integral to the work, as with the Argentine horse racing commentator or the woman in Mexico City who teaches sex workers how to simulate a blow job on the phone. Occasionally, we see people in entertainment or service industries: one of the most striking films is Frida Kallejera, where street artist Bani Khoshnoudi paints a picture of Frida Kahlo for sale, while dressed as Kahlo.

Many shots capture people manufacturing, or making clothes, and their juxtaposition highlights the diversity of work and its gendered nature: in Johannesburg, a Building Inspector abseils down a tower block, his face shot from above, full of exhilaration, before a fade and cut to several women intricately sewing in a studio. The films capture danger, as with the engineer clinging to girders as a train passing over a bridge in Hanoi before going back to his maintenance work, and boredom, with a shopkeeper looking after an empty store in Bangalore; despite occasional moments of levity, we don’t see people during their breaks, or slacking off, and the films manage to avoid much sense of participants knowingly performing for the camera, their brevity keeping them sharply to the point.

In the Cooper Gallery’s study room, three shorter films can be watched on smaller screens with headphones. The most compelling is Catch Phrases – Catch Images (1985), in which Farocki and philosopher Vilém Flusser deconstruct a front page of West Germany’s Bild newspaper. It feels somewhat tangential to the exhibition’s main theme – the development of mass media in the industrial period as a means to inhibit class consciousness and persuade newly enfranchised workers to vote against their own interests is only implicit – but it’s as acute a work of media criticism as Farocki’s reflections on cinema after the Lumières. Farocki and Flusser discuss the choice of stories, about disasters and murders rather than (say) industrial relations, and how the text and image are inseparable, subtly working to prejudice readers into sympathising with a conservative mindset.

This is contrasted not with Farocki’s documentary about Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub working on an adaptation of Kafka’s Amerika (which they retitled Class Relations), but with a 45-minute interview with Georg K. Glaser – Writer and Smith (1989). This raises all sorts of questions: how separate are Glaser’s writing and smithing, as both are forms of creativity? Does that matter? Does he write about his artisanship, or should he? The key thing here is that Glaser had wanted not just to escape the factory, like the people so jubilantly doing so in Louis Lumière’s film, but to continue working, only now with total control over his production. Glaser may not quite achieve that, but manages to find genuine dignity in his labour, and across these works, we can clearly sense that Farocki wanted the same for all the workers of the world.

Harun Farocki, Consider Labour, is at the Cooper Gallery, University of Dundee, until 1 April