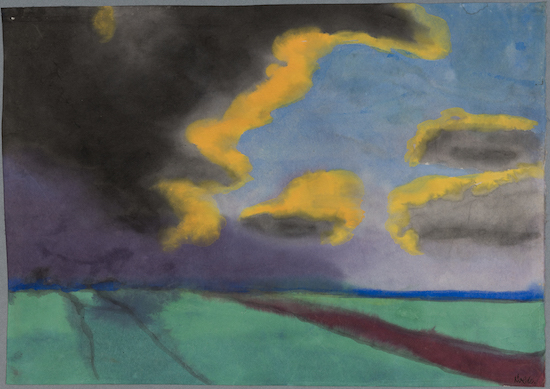

Emil Nolde (1867–1956) Expansive Landscape with Clouds, Watercolour on Japan paper, Kunstmuseum Bern, Legat Cornelius Gurlitt 2014, Provenienz in Abklärung / aktuell kein Raubkunstverdacht © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Everywhere, as exemplified at this juncture by Paul Manafort’s malfeasance, there’s talk about lies and liars. Getting to ‘the truth’ has never been easy as is spectacularly evidenced by the story of the so-called Gurlitt ‘hoard’, now on show at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin.

We might begin the tale in 2010 when customs officers detained the elderly Cornelius Gurlitt when he was entering Germany from Switzerland. He was carrying around £7,500 explained away as the proceeds from an art deal. The tax authorities were intrigued and in 2012 his apartment was searched. They found art – a lot of it – 121 framed and 1,258 unframed works. Try to imagine the excitement of flicking through the pile of prints and recognizing that this must be a Picasso, that a Matisse, and, wow, isn’t that a Waterloo Bridge by Monet? Cornelius said that the works belonged to his father Hildebrand. And this is where the saga becomes as murky as one of those foggy London evenings old Claude painted from the fifth floor balcony of the Savoy.

Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956) was a complicated man living through a convoluted era. Nuance is all in trying to make sense of his life. He was wounded twice in WW1 and withdrew from active service on the grounds of shell shock. His sister, Cornelia (1890-1919), was an artist and, on the evidence of her work on display here, she has been most wrongfully forgotten. One critic of the time called her ‘perhaps the most brilliant talent of the young Expressionist generation.’ Hildebrand hung out with the Expressionists and acquired their works as a young museum director in Zwickau. He dug the new, rejected the old, and became an exemplar of Weimar modernity. And then the fascists took over.

He first offered his services to the Nazis in 1938 in the immediate aftermath of the Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition when Hitler ordered that more than 20,000 art works be removed from German museums. Goebbels wrote in his diary ‘we even hope to make money from the garbage’. Hildebrand Gurlitt would be one of the men charged with selling them abroad; it is thought that he obtained 3,879 confiscated works. He sold in Paris and also became Hitler’s chief buyer of French art. Between 1941 and 1944 he sold art worth 9.8 million Reichsmarks. He was making money from the victims and the oppressors.

Gurlitt Cornelia (1890–1918) Untitled (Two Women) Brown ink and watercolour on paper, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bequest of Cornelius Gurlitt 2014, Provenance undergoing clarification / Currently no indications of being looted art

After the war he was put through the denazification tribunals twice and was ‘exonerated’. He presented himself as a victim – this evidenced by his losing the job in Zwickau through his support for modernism. And under the disgusting Nuremberg Race Laws Gurlitt was declared a ‘quarter-Jew’. One hypothesis holds that Hildebrand Gurlitt decided to enter into the moral maze of the Nazi art trade in the hope that it might protect him and his family from persecution. But he made a lot of money sourced from the fears of others. He kept some works of questionable provenance, and then died leaving the collection and the burden of conscience to Cornelius as his highly dubious legacy.

So was Hildebrand a puppet or the puppet meister? One view might have Hildebrand as something of a spiritual brother to the fictional Private Shulz, the hero of the eponymous BBC comedy drama from 1981 starring Michael Elphick and Ian Richardson. Shulz is a shyster in the S.S. and a war profiteer charged with setting up a currency forging operation. He then has the chutzpah to try and rip off the Führer himself. Hildebrand Gurlitt appears to have shared much of this amoral cheek but unlike the TV show the reality of such perfidy was not remotely amusing. In the violently genocidal world of the Nazis Hildebrand Gurlitt would not be the only person whose moral compass was prone to deviation.

But what of the art itself – is it any good? Unsurprisingly much is… some of it very fine indeed. If we begin with those artists branded ‘degenerate’ there are some remarkable works by Otto Dix that document the poverty and desperation of the Weimar Republic era such as Leonie (1923). One of the sad haggard prostitutes Dix so scabrously documented is shown in a pathetic state with her plumped up scarlet lips, her tatty broad brimmed hat and moth-eaten fox fur collar. Then there is the watercolour Girl (Mädchen) (n.d), featuring one of the demi-monde from the dancehalls with her shining neon lit face and startled cocaine stare. Here too another undated work, this time by Rudolf Schlichter also titled Girl (Mädchen) that sees an exhausted and heavy lidded sex worker caught in an insomniacal slump. Her brown leather laced boots are a trope beloved by Schlichter, the artist being a well-known fetishist. And in the same room here we find George Grosz’s Friedrichstraße (1918) – a crowded chaotic street scene with beggars, military types, and streetwalkers all passing under the railway bridge of said Berlin avenue: the city as demonic energy incarnate.

Otto Dix (1891–1969)Girl, Watercolour, coloured pencil and opaque white on paper, Kunstmuseum Bern,Bequest of Cornelius Gurlitt 2014, Provenance undergoing clarification / Currently no indications of being looted art, Kunstmuseum Bern VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018

Elsewhere there’s the threatening purple sky of Emil Nolde’s Expansive Landscape with Clouds (n.d.) with its redemptive streaks of yellow sun. The woodcuts by Munch, Kirchner and Erich Heckel are great – the latter’s Wounded Man (1915) has some of those wooden puppet-like hand and arm gesturing’s beloved of David Bowie and Iggy Pop.

Some of the bigger names disappoint – Monet’s Waterloo Bridge (1903) is muddy, polluted. You feel like coughing and hacking with your first glimpse; this view lacks the warm evocative fug of his other Thames masterpieces. And there are better Beckmann’s than the uncomfortable white privilege caught in the sketchy beach scene – Zandvoort Seaside Café (1934).

Cornelius the son died in 2014 and bequeathed all his property to the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern. Much of the fascination around the Gurlitt ‘hoard’ revolves around stories about provenance and restitution such as the return of Matisse’s Seated Woman (1921) to the Rosenberg family in 2015. Contrary to initial media reports on the find much of the collection is now being argued as having belonged to Cornelius Gurlitt ‘legally’. The phrase ‘currently no indications of being looted art’ appears not infrequently in the catalogue. Even so the opprobrium Hildebrand Gurlitt’s behaviour deserves is appropriate in this analogous era of mendacity.

GURLITT: STATUS REPORT – An Art Dealer in Nazi Germany is at Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin, until 7 January 2019