A recent article by Mike Watson in ArtReview asks the question is art too polite to fight the far right? Perhaps the answer lies in recent art history. What action should you take when you see your country steadfastly refusing to face up to the sins of its past? How do you react as you watch it glorifying a barely constrained hard right ideology? Why are you hearing about a resurgence in anti-Semitism? What do you do?

Ask an Actionist.

If you are Günter Brus and it is Vienna University, 7 June 1968, you do this: jump up on a table in a packed lecture hall, cut your chest and thighs with a razor blade, take a piss into a glass, then down a slug, and next squat naked before singing the national anthem whilst having a shit.

You get sentenced to six months in jail; you flee in exile to Berlin, and then kick off a few more loud provocations.

Very few artists today seem up for such heroics; Brus has been there, done that.

Set back from the Baroque glories of the Upper Belvedere palace with its imperial views over Vienna is the contemporary space 21. Here we find a comprehensive retrospective of Günter Brus’ life work to be seen in daring counterpoint above the significantly more restrained sculptures of Rachel Whiteread (recently shown at Tate Britain) on the floor below.

We follow the evolution of Brus’ practice from his early gestural paintings such as Untitled (informel) (1961). Imagine paint thrown by an uncoordinated Franz Kline as if his arms were writhing with St. Vitus Dance. These early works are a messy, uncontrolled flinging of monochrome pigment. Others, such as Untitled (Informal drawing) (1960), look like the product of a dyslexic Japanese calligrapher with co-existent Attention Deficit Disorder. Maybe you had to be there to see Brus toss the paint around to get the full effect. What we have here are the relics, the detritus after the storm.

From there we move on to the black and white photographs of his actions such as Ana (1964) named after his wife. Here we see him semi-naked in the studio; he’s covering himself in paint from a bucket and then throwing the stuff at the wall in scenes reminiscent of Nicolas Roeg and Donald Cammell’s Performance (1970). There’s also a bicycle wheel in their somewhere. He smears a naked Anni with paint – what we confront looks highly disturbing, violent.

These images are not dissimilar to the infamous Lustmord paintings from the 1920’s by George Grosz, Otto Dix, and Rudolf Schlichter. Those artists, and their earlier takedown of insecure men that referenced the far-right extremism of proto-Nazis such as the Freikorps, prefigure Brus’ anger.

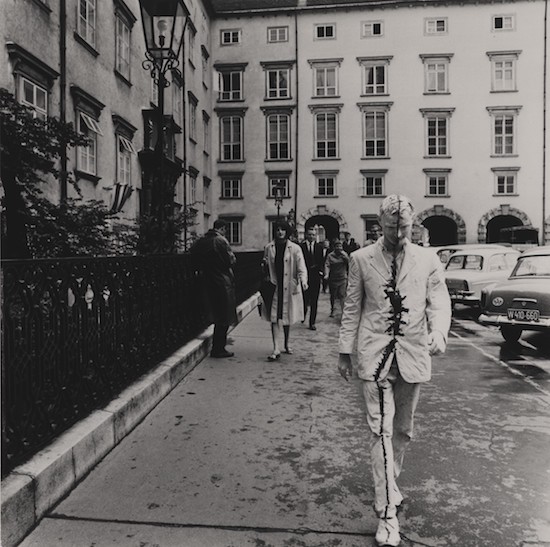

With his action Wiener Spaziergang (1965) he dresses in white suit, white shoes, and paints himself white too just like one of those trashy urban statues we see hanging around city centres today. Brus did that stuff first. He bisects his body with a thin line as if cleaved by a claymore and then goes for a walk in central Vienna. We see him in grainy footage get out of a car and stroll through the Hofburg. He looks like a creepy ghost. There’s a great still of him talking to a policeman in a leather cape and white cap outside a bourgeois gallery on Stallburggasse near Thomas Bernhard’s favourite café, the Bräunerhof, with the sign NEUE KUNST behind their heads. I suspect the owners of that outlet had very little interest in Brus or his work.

Transfusion (1965) looks deeply transgressive even today – here he poses again with Anni, this time in colour, both nearly naked with Brus shoving his nose, seemingly connected by thin plastic tubes, up against Anni’s apparently bleeding vagina. In the show’s catalogue the art historian Ana Petrović suggests that Brus paved the way for Austrian feminist artists such as VALIE EXPORT to use their own bodies in their works. She reads Transfusion as seeing Brus as a newborn finally separated from the mother figure; a Freudian nightmare as performance. She also argues with some confidence that with other later works such as Ordeal (1970) Brus had prophetic thinking on gender role-play and identity. Ordealwould be his last action. While hiding in Berlin in 1972 he hangs out at the Café Exil – favoured in later years by Bowie and Iggy – and designs their menu and drinks card.

He then makes collage-like graphic narrations. These are his ‘image poems’, his work now more text-based, but the terse criticisms of Austrian society persist. Light relief of a sort comes with the pitch-dark humour of Guinea Pig Experiment (1971). Here are four drawings featuring said rodents in various scenes of existential dread. Specifically each is threatened by a tethered erect cock restrained by cords that are about to be cut by a scalpel. You follow the visual logic like the satisfying step-by-step praxis of that daft board game Mouse Trap – an axe will fall on the rodent in one, a match will set another on fire, the third is doused in benzene, the last gets a pin up its arse. This is an Austrian precursor to the depravities of Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory (1984).

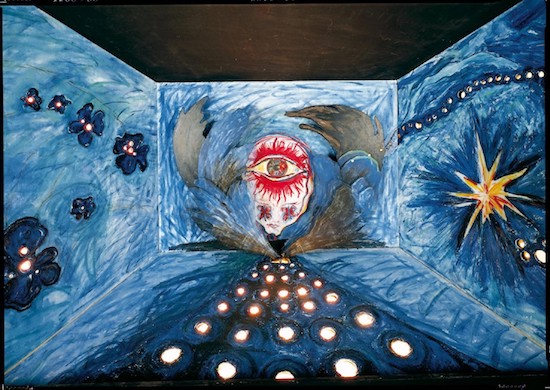

Brus was keen on collaboration and there are works here done with other notorious Austrian figures such as Arnulf Rainer, some surprisingly pretty such as Innerhalb der Märchenscheide (1984), a floral figurine that wouldn’t look out of place in a child’s scrapbook. There’s also a bitter-sweet sequence of drawings about van Gogh’s last four letters to his brother Theo made with his fellow Actionists – Vincent: Brus with Muehl and Nitsch (1984/1985). Here too is an oil pastel sequence, Cyanide-Cyclamen (1982/1983), done on packing paper that is quite exquisite – not a descriptor you might expect to use of Brus – complete with beautiful script and drawings of fruits, a wasp.

More recent text and oil pastels such as Bedenkliches Allzumenschliches (2000) feature drawings of Friedrich Nietzsche and suggest Brus has had a more than significant influence on Germany’s artistic agent provocateur of the moment (and fellow Nietzschean) Jonathan Meese. A twelve-part sequence of rapidly drawn oil pastels on paper, Kleiner Ausflug in vermutliche Uraschen (1989), reverts to Brus’ irrepressibly vulgar sense of humour and his ongoing obsession with motherhood, his feminism. One of these has a female figure and a text I daren’t argue with: God is a woman: a midwife.

Günter Brus, Unrest after the Storm is at Belvedere 21, Vienna, until 12 August 2018