Giorgio Griffa, Rosso sotto, 2003, Acrylic on canvas,Photo Giulio Caresio, courtesy Archivio Giorgio Griffa and Casey Kaplan, New York

Art, says Giorgio Griffa, is a process of “forgetting myself.” He begins each of his cosily minimal paintings with a single mark “and then the second sign and the third sign and every other sign are the ones requested by the first sign.” But behind this apparent simplicity lies a sensitivity to materials, a depth of thinking sufficient to place the Turin-born artist in a league entirely his own.

He was speaking at the opening of his new show at London’s Camden Arts Centre, his very first solo show in the UK. But the sentiment was familiar. He had said something similar to me when we met two-and-a-half years ago in Geneva, when I came to review his exhibition at the Centre d’Art Contemporain for Art Review. “The beginning is something casual,” he told me. “But after the beginning, everything becomes necessary, because it is the work that asks what I have to do.” The problem, he explained, is finding the proper attitude of “passive concentration, to understand what the work is asking of me.”

We had been sat next to each other at lunch, at a little cafe round the corner from the Centre in Geneva’s Quartier des Bains. His posture was upright, almost stiff, as he dined. His bearing reminding me that his actual profession, for most of his life, was not artist, but lawyer. “A lawyer to earn money and a painter to earn… something else,” he laughed. “Someone asked me, how do I do both?” he went on. “I said, I don’t know who is Jekyll and who is Mr. Hyde.”

Though he studied law and not art, and was never formally trained as a painter, Griffa started painting as a child, when he was just nine or ten years old. Talking to Camden Arts Centre’s director Martin Clarke on Thursday, he cited the experience of seeing a work by Piet Mondrian at the age of fourteen that changed everything for him. That was the moment he credits with the realisation that “traditional painting was not for me.”

“I understood that a painting must live in its present, not the past,” was how he put it to me back in 2015. “I never chose between abstract and figurative,” he went on. “The problem was to change the aspect of the work of the art, from an art which takes lifeless material, to then make it living.”

“Now we know that all materials are living,” he said. It was this realisation that transforme his practice, “from a relationship in which the artist is dominating the materials to another system, in which the artist is speaking with the material.”

So it becomes a sort of dialogue? I suggested.

“Yes,” he said.

And perhaps not just a dialogue, but a three-way conversation, between the artist, the material, and the spectator too?

“Very, very important this aspect. Because I think that in every time and in every civilization, in art there has been not only a way that goes from the artist to the work to the public, but there is also another way that goes from the public back to the work. Everybody sees different things. This is a very important thing. Because that is where the life of art works comes from, the possibility to continue to live after their time.”

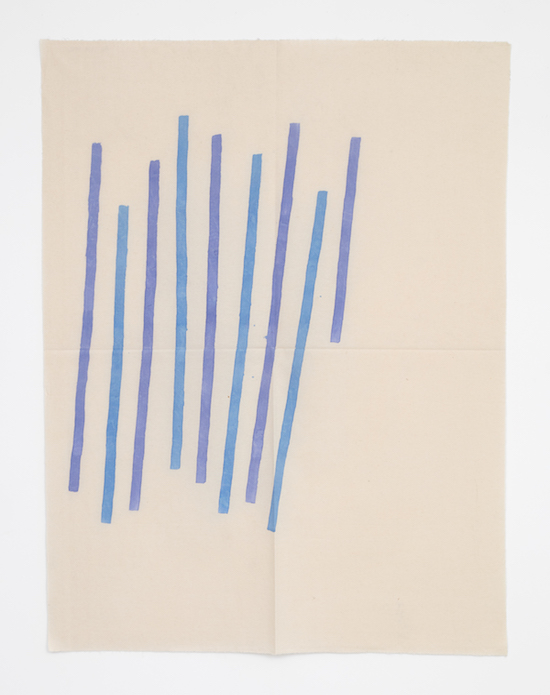

Giorgio Griffa, Obliquo, 1979, Acrylic on canvas, Photo: Jean Vong, Courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York

Griffa’s paintings often consist of little more than a series of lines or small dabs on a large, unstretched, unframed canvas. But they somehow suggest so much more. By allowing his lines to flow over the edge of the material, by halting his succession of marks at a seemingly arbitrary midway point, he is able to suggest their continuation beyond the canvas itself, pointing towards some infinite that must be filled in by the imagination of the spectator.

It is in this aspect of appreciating the “life of materials”, their co-creation of the works that Griffa sees the connection between his own work and that of the Arte Povera group who he socialised and exhibited with in Italy in the 1960s. “I received very important ways of working from Arte Povera,” he told me. “[Gilberto] Zorio with his chemicals, [Giovanni] Anselmo with leather – in every work, the hand of the artist was no more given to a domination of the material but was in service of the material. I think that, in a way, that comes from the hand of [Jackson] Pollock. Pollock gives his hand at the service of the dripping of colours. And in my work the colour becomes dry and when it becomes dry, it works together with the fabric, with the paper, and with the memory – 30,000 years of memory of humanity is in that, here.”

This theme of memory was one he returned to, talking to Martin Clarke in Camden the other night. “Painting has inside it the story of humanity, the story of that part of humanity that is not visible. Life goes beyond the border of reason, and painting records that history.”

“I work in rhythms,” he went on to say. “Everything is rhythmic.” And I was reminded once again of our conversation in Geneva back in 2015. I had already been struck by the rhythmic, musical qualities of his work, so I was not surprised when he turned to me and said, “There is a lot of music in my work.”

Do you listen to music while you paint? I asked.

“Yes,” he replied, adding “rhythm is the beginning of knowledge and the beginning of poetry.”

What music do you listen to while you paint?

“Generally I like all the classical music. Old music and modern music. You play Mozart in the moment when you like Mozart.”

In 2009, the 2000&Novecento Gallery in Reggio Emilia paired your paintings with music by composer Luigi Abbate. Do you think the music helped people to understand your work?

“I think so, yes. I would like to have the possibility to do a show where there is sometimes poetry, sometimes music. You can play Mozart or the new jazz. I read a lot of poetry and when I work there is always music.”

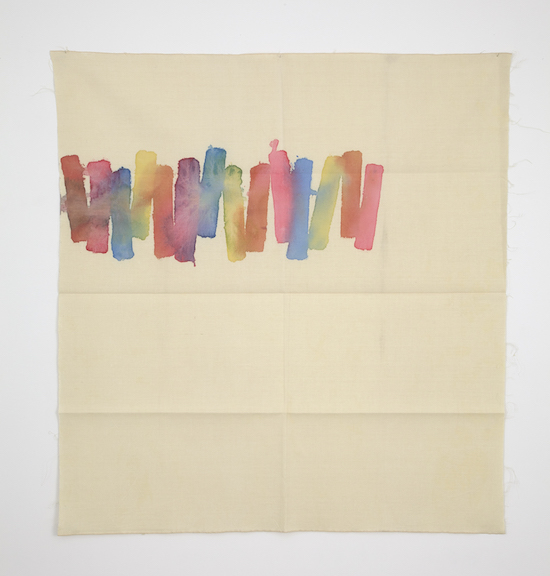

Giorgio Griffa, Policromo, 1976, Acrylic on canvas, Photo: Jean Vong, Courtesy the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York

Before we parted, I wanted to ask Griffa one last question about the folds in his work. His paintings, unstretched and unframed as previously mentioned, are stored folded up into quarters or eighths (depending on their size). There is something almost bureaucratic about this choice, as if filing things away, matter-of-factly. But the creases left by this process of folding remain visible in the displayed works creating a softer, subtler riposte to the modernist grids once skewed by Rosalind Krauss.

“For me,” he said, “the fold is only one moment of the story of that material. The material has its own story because every material is a protagonist in my work and so the canvas is not an inert surface but it, too, is a protagonist. So it has its own history and in this history they have been put in storage and the normal storage of fabrics is to fold, and so –. The work lives its own life. The work lives.”

Giorgio Griffa, A Continuous Becoming, is at Camden Arts Centre, London, until 8 April