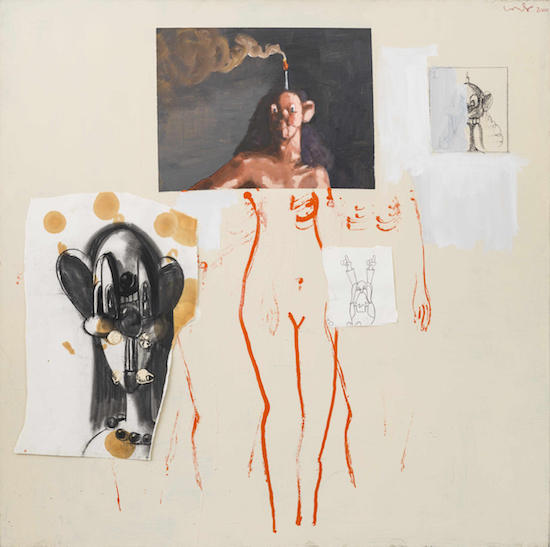

George CondoPod Collage, 2000Öl auf Leinwand, 132,7 x 132,1 cmSammlung des Künstlers,

New YorkCourtesy Sprüth Magers und Skarstedt© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017 Foto: © George Condo 2017

In which George Condo goes mano a mano with some of the greats of modernist art collected by Heinz Berggruen.

Hemingway once wrote that, as a writer, he ‘started out very quiet and I beat Turgenev. Then I trained hard and I beat de Maupassant. I’ve fought two draws with Stendhal, and I think I had an edge in the last one. But nobody’s going to get me in any ring with Tolstoy unless I’m crazy or I keep getting better’. Taking on the painterly equivalents of Mr. Tolstoy begs this question – is Mr. Condo mad or is he gaining in strength? Maybe he’s even playing a different game altogether?

The Berggruen goes all Madison Square Gardens on us for the big fight and sets Condo up against a tag team of Matisse, Klee, Cezanne and Picasso. Condo clearly has protean skills, but his form is predictably unpredictable. As Simon Baker writes, he has ‘worked against continuity, against linear development and rational coherence.’ Condo’s references and inspirations, again in Baker’s words, ‘ricochet deliriously around the canon of Western art history.’

Condo’s bravery is admirable but he risks getting critically bounced out the ring. Most artists would think such a stunt quite deranged, but Condo is an old hand at creating what he has called ‘fake’ Old Masters. He is unafraid of being boxed in by art historical notions of ‘progress’. He pulls his gloves on with grim determination and begins the slugfest. Seconds out, round one.

Condo toys with Paul Cézanne and his still life innovations by hitting us with His Brain (2009), a painting of two apples. Condo’s luscious red fruits are here seemingly spliced together, conjoined like the hemispheres of a cerebrum. This melding thus references the early advances in modernism initiated by Cézanne’s inspired experiments with spatial depth that he realised as true.

Condo next provokes the master with some feints and jabs such as The Return of Madame Cézanne (2011). This is a tentative poke below the belt – it’s Cézanne’s wife all right (Madame Hortense Fiquet), with her hair in a prim middle parting and her insipid stare of ennui preserved, but what has Condo done to her neck? He’s elongated it monstrously; she looks like one of those Kayan women from Myanmar without the rings of brass coils. Cézanne disinherited her so it is possible that Condo’s frightfully disrespectful image of Hortense might have appealed to the elder were he to suddenly manifest in the flesh at the Berggruen. He’d have taken the insult on the chin. Even contemporaneously, it should be noted, Cézanne’s paintings of his wife were described simultaneously as ‘monstrosities’ or ‘masterpieces’. One of the many joys of this show is imagining what reaction Condo’s works would have provoked were his betters to rematerialise. The idea of confrontation reanimates the earlier works, revitalizes them. The older works in this context are reified, their aura rebooted. In short they have clout; they make a comeback.

Installation view, Museum Berggruen© Succession Picasso / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017Foto: Timo Ohler

Condo is next paired up with his fellow southpaw – Paul Klee. Some pundits might have thought this a bit of a shoe-in for Condo given Klee’s puny markings, his tense scratching movements, his tentative rabbit punches restricted by the awfulness of his tightening scleroderma. But Klee is a tougher opponent than Condo might have bargained for. He’s got better, wittier, titles for a start – like Fatal Bassoon Solo (1918). Condo’s notion of ‘artificial realism’ chimes with Klee’s worlds where the real might look imagined, the imagined real. Condo’s Sisyphus (1985) has the quietude of the best Klees, a solitary oval atop a volcano shape rendered ochre on an indeterminate orange background. But this clash is clearly bruising for Condo and a comic work like his flimsy Fantasy Bird (1989) has only half the charm of Klee’s universe and its zoomorphic forms. The American’s references to the animal world are more grotesque and quote from animation – the borrowings of dental overbites from Bugs Bunny cartoons, the hamster cheeks and exophthalmic gaze of his delirious ‘pod’ creations. The curator, Felicia Rappe, allows Condo’s march to progress for the next contest with Matisse.

Condo’s View of Cap D’Antibes (1989/90) shows he has the skill to run off an azure seascape with the turquoise railings of a promenade in an easy post-Fauvist manner, as with Matisse’s own At the studio in Nice (1929). And Condo has no problems imitating some cut-outs either, his Hands (1997) takes the central motif from Matisse’s Vegetal Elements (1947), cuts the number of fingers from four to three and conjures up a child-like construction as pleasingly naïve as the Frenchman’s. Part of the game here is to watch out for such correspondence, for the chimes of influence, the bells that ring when you recognize a pictorial gesture, the motifs that Condo has grabbed after. These are not parodies or impersonations – Condo’s works tussle with tradition in an attempt to wrest some kind of new, even if only as a documentation of struggle against the concept of what Rappe calls ‘linear evolution’ in art.

George Condo, Study for a Clown, 2009, Courtesy Sprüth Magers und Skarstedt© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017Foto: © George Condo 2017

His final challenger is Pablo Picasso, the undisputed twentieth century champion of pictorial shock and distortion. The bulk of the confrontations we see on the walls at the Berggruen are with the Spaniard, a bare-knuckle bout with yet another southpaw. The key work here is Picasso’s drawing Brothel: Degas with his Sketchbook, Celestina, Three Prostitutes and a Moroccan Cushion (1961). Here a staid, be-suited, Degas confronts the women who pout and flash and gape in Picasso’s late, typically lurid fashion. The drawing is a provocation, a rebuff, but also a not-so-playfully compassionate slap at poor dead Degas that says something like – I know you were here, I know you were flawed just like me, but that’s just the way things are Edgar, that’s just the way things are. And this rebuff is exactly what George Condo recapitulates in this duel with Pablo Picasso.

Some might see only violence done here, disrespect and blood on the canvas, but Condo’s irreverent works square up to his elders and betters and ask us to view them with a renewed admiration. The fight goes the whole fifteen rounds, taking in Picasso’s Blue Period as with the Portrait of Jaime Sabartes (1904) shaping up to Condo’s frightening The Missionary (2004). Each illustrates a resolutely skeptical attitude to the Catholic clergy.

There are not as many of Condo’s gloriously improvised drawings such as Linear Mass (2001) on display here. Were one his trainer at the ringside, you would have been tempted to suggest that he should have pulled that one out of the bag. Or maybe another of his brilliant later ‘drawing paintings’ like Celestial Bodies (2010) that might have floored Picasso in admiration, if not in actual corporeality. One that does appear here is Surprised Couple (2009) where a pair of feral faced lovers are caught in flagrante, their skins economically highlighted with pink pastel, their grimacing scarily directed at us like a pair of mating wild cats.

Installation View. Museum Berggruen© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017Foto: Timo Ohler

Here at the Berggruen, then, we see George Condo appropriate many lessons and quotations from his predecessors in an attempt to revivify the past. In this he is largely successful. The clash of his works with those of the aforementioned masters forces us to review and renew our reactions to the canvases of the permanent collection. We are reminded of their contemporary radicalism and appreciate their persistent daring.

Condo’s own portraits, landscapes, nudes and variations on the still life are studded with samplings taken from his classical influences. Wacky juxtapositions abound. Abstraction and figuration are conflated for Condo – he doesn’t see a distinction. This is painting about painting about painting. There are layerings, effacings and some slashing of planes done jokily, as with the chopper in his portrait The Butcher (2009). Punch-drunk perhaps by the extent of his ambition and cheek, we conclude that his meta-paintings, his endless counter attacks, provoke a revision of the received wisdoms of art history as it is classically reported.

George Condo, Confrontation, is at the Museum Berggruen, Berlin, until 12 March