Gee Vaucher’s reputation as part of anarcho-punk band and collective Crass (1977-84) has preceded her renown as an independent artist in the past. This major exhibition, currently on show at Firstsite, Colchester, succeeds in bringing her far wider body of work to the gallery-going public. Vaucher’s work for Crass appears as just one of several powerful, engaging and interrelated bodies of work, in media including illustration, collage, painting and installation, which she has produced, largely as a solo artist, over the last five decades.

Serendipitously Vaucher’s profile was raised just two days before the opening of her show through the inclusion of her image, Oh America (originally the cover for the Tackhead LP, Friendly as a Hand Grenade, 1989), on the front cover of The Daily Mirror to illustrate despair in the wake of Donald Trump’s US presidential election victory. The newspaper was alerted to the image from its widespread use as a visual meme on social media profiles following the news.

Vaucher’s work being influential without its audience necessarily having knowledge of its creator is nothing new. Crass subsumed their identities as individuals into a largely anonymous collective, which put into practice the anarchist principles they promoted. Nevertheless, her iconic designs critiquing political power, corruption and war – as well as Thatcherism and its harsh impact on society – came to define the oppositional and politicised punk aesthetic of the 1980s.

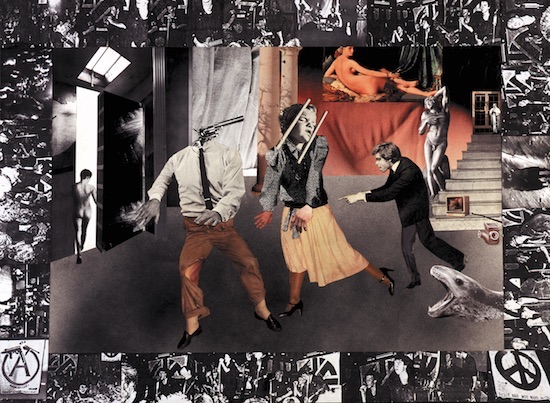

Seeing the original paintings and collages she produced for Crass and her self-produced publication, International Anthem (1977-) is one major highlight of the show. The small, gouache paintings show incredible deftness in their brushwork and the collages are meticulously constructed. Having these works here also reveals the process of their original construction, after which they were reproduced as record sleeves, inserts and ephemera or fanzine illustrations respectively.

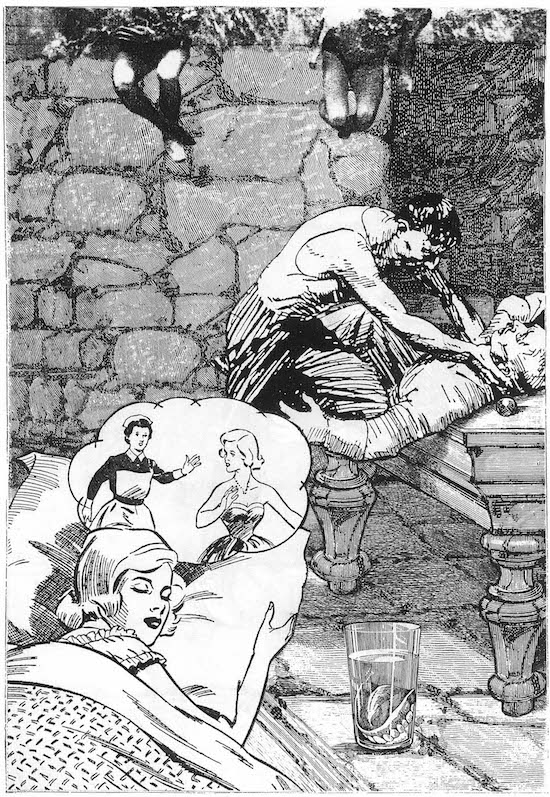

The exhibition also showcases her early, pre-Crass illustrations, which she produced for major magazines, including the New York Times, New York magazine, Ebony and High Times, while living and working in New York (1977-79). It is here that we can see the nascent development of her satirical design language, which was extended through her work with Crass (1977-84) and International Anthem (1977-). Vaucher enjoyed the supportive artistic environment that grew out of the economic downturn and leftwards political orientation of 1970s New York. In particular she cites the open relationships she was able to foster with arts editors and cheap living costs. Her illustrations comment on contemporary issues: family breakdown and problems or the excesses of a rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle. She also spoofs societal aspiration and idealised representations of domesticity in the media as-well as commenting on political news.

aucher, G, Sunday, A Week of Knots, 2013

The exhibition includes her last job for the New York Times entitled Attack on Gays –Central Park (1978). The magazine refused to publish this image due to its perceived offensiveness. Having already had to alter one image a magazine had considered inappropriate, this led Vaucher to resign, and ultimately return to the UK.

It is this distinctly rare unwillingness to play the game of art-world or commercial success which Vaucher has consistently maintained throughout her life’s work. This has affected the development of her design language, critiqued from a position she has continually sought not to compromise. This autonomy was a feature of her early avant-garde experimentation with performance-art group EXIT, which she set up with art-school friend Jeremy Ratter (Penny Rimbaud) in 1968 (Rimbaud later went on to found Crass with Steve Ignorant aka Williams).

The exhibition includes photographs of EXIT art performances to illustrate Vaucher’s early creative development. This autonomy facilitated the development of a politicised critique, which she developed through her early illustration work for mainstream publications and found a particularly vehement outlet through her work for International Anthem and Crass (1979-84).

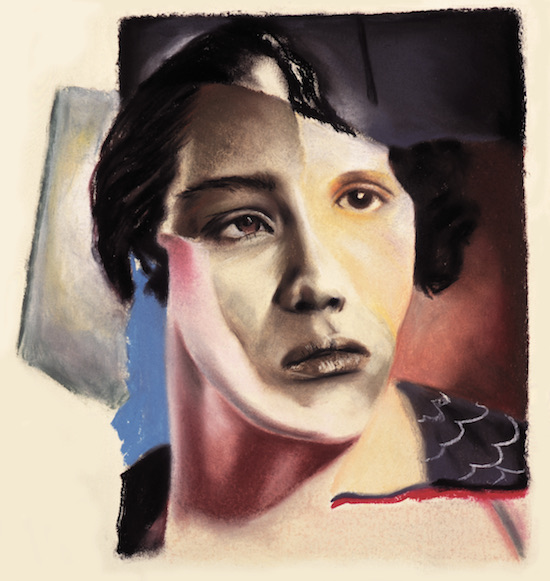

Following this period her work took a more introspective turn. The exhibition includes a series of her portraits in pastels from the 1990s. All the portraits feature female subjects whose figures or faces are partially altered or abstracted.

Vaucher, G, Drawing in pastels. 1994

Despite the term ‘introspective’ in the exhibition’s title, there is very little solipsism here. Vaucher only includes three self-portraits from her collection. Much of the show is instead focused on the psychological dynamics of human interaction within various contexts of power imbalance.

Vaucher has maintained a commitment to animal rights and vegetarianism throughout her life, which is a key component of her wider politicised critique of societal power inequity. One room features her work exploring human-animal relationships. Included here are photographic collages from Animal Rites which she originally self-published as a book (2004), and her sculptures of plastic animals fused with dolls’ heads. Both groups of works comment on the human tendency to project anthropomorphic qualities onto animals.

For Animal Rites, Vaucher took old, monochrome photographs of people interacting with animals. She then collaged human facial features with those of the animals in the original photos. The humans bestow attributes of playfulness, empathy, wisdom or submissiveness to the animals. Overall the collages send up the absurdity of how humans define these relationships. Vaucher’s quote, “All Humans Are Animals, but Some Animals Are More Human than Others, “appears alongside the images, blurring the boundaries between the definitions of human and animal existence.

Gee Vaucher, Introspective, is at Firstsite, Colchester, until 19 February