Art’s potential is that it’s shared with, and informed by, audiences. Furtherfield works to create the participant’s agency with subjects from bioengineering to the influence the internet has in shaping how we will think in the future. Published this month is the book Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain edited by Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett, Nathan Jones, and Sam Skinner, a future-artefact of “a time before the blockchain changed the world”.

On the 15th of September, Furtherfield launches the onsite and online exhibition Are we all addicts now?, developed in collaboration with artist Katriona Beales, artist-curator Fiona MacDonald, clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones, and curator Vanessa Bartlett. The show examinines this distracted time in which our conversations and actions are routed towards the glow of the screen and its whispered promises of connection and intimacy. A series of gifs designed for the exhibition can be accessed on Twitter via the hashtag #addictsnow. The risk and curiosity engendered by the present is critical to the context of Garrett’s curation of the exhibition Children of Prometheus which has been held at both Furtherfield, through the summer, and also as Monsters of the Machine at LABoral.

I always object to the idea that art appeals to a particular community, and that any community outside of that doesn’t have anything to offer. Do we need to keep hearing this repetitively?

Marc Garrett: We need to look at new ways of engaging with life other than this monolithic, singular society. Dark matter by Gregory Sholette shows the fact that dark matter is seventy percent of the universe. It’s a very large part of the universe that we have not discovered and we can’t see. Sholette was reversing back to the planet earth to see what’s happening on the planet. In darkness you’re coming down and you just see all the lights on, the shiny bits. Well that’s like twenty-five to thirty percent of the planet. That’s all you’re getting. The seventy percent – like in the art world – is unseen. It’s not allowed to be seen and it’s indigenous.

The way we approach it is as pre-colonial indigenous, the fact we are being data mined, corralled into new social engineering through technology and austerity. We are collectively indigenous from a different perspective, as we are now being looked down upon. If that’s the case if we can share peer indigenousness with others from different backgrounds then you have got a really good network of culture that you can work with. Whether it’s from a council estate down the road or a clapped out farm in Arizona. You have got stories to share and you’ve got art to make.

Alan Sondheim, 3D glitch avatar video, performed in Second Life

Furtherfield has such a precise context, there’s the location in a public park and the environment and your focus on technologies and evolving technologies.

MG: It’s like a hidden secret! We’re showing real, avant-garde art and it’s like it’s not allowed to be seen. What’s interesting is that we survive so far, by not appeasing. We’ve got a community online, we’ve got an email list with thousands of people on there, we’ve got thirty thousand subscribers to Furtherfield online, and a very high readership of articles and reviews, which we write ourselves through peer-to-peer critique. We’ve built our own website, so there’s a flourishing culture that’s come out of this. You realise that you’re not on your own; you’re actually connected to a lot of different people that have similar views, interests and questions.

We need to recognise that complexity of an audience, the fact that an arts audience does not need to originate from an art culture. We should ask questions as to why interesting people outside the arts do not go to galleries.

MG: There are some extremely interesting people who don’t, who hold equally fascinating critiques. In a way that’s what makes art a wider conversation: you can’t fit it in a framework. The narrative should be from the bottom up. Then you investigate that narrative and build something out of it. You have a conversation about what that is. What we like is that there’s this freedom out there but at the same time we really like discipline. If you are disciplined you’re focused, but if you’re free you’re free. It doesn’t mean that you’re blobbing around everywhere. It means you’re free to do what you value and things that you believe in.

The capacity to look at the transformational, to move material or idea from one thing to another.

MG: An exhibition isn’t about the space, or containing something. It’s actually connected to the world. It’s not isolated, whether it’s networked, to do with responsibilities culturally, it’s not an escape route. It’s not hiding, which a lot of art thinks it is. It’s like, oh look you can hide here, and look at art-for-art’s-sake. Which is fine but there’s a lot of it. The real ideas are out here being breathed everyday. Just like Albert Camus or Kathy Acker – they breathed the real ideas. That’s why they were so good.

That sense of what the world does, and what happens when art connects with the world. Here the promethean becomes really fascinating, it’s something risky or precarious.

MG: Prometheus is us, and the perfect Promethean monster is Trump. But then you’ve got a networked monster like bad education, bad money, killing the forests, the killing of animals. All this is the kind of arrogance of humans. That think they own everything, that’s Promethean. Brexit is a good example, people don’t think about anything, it’s all based on prejudice. Not based on what would happen. It’s so obvious.

So everyone thought the nation would vote remain, so they could have this individual moment of protest. Then suddenly there it is…

MG: I know people who voted leave, that have completely changed their minds since. Friends in Cornwall – half of Cornwall is funded by Europe, that’s going now. They’re going to go back to open tin mines again I think, they’ve got nothing else. To me it’s a bit like the Iraq war: you know it’s wrong, you know people are going to get hurt, so why do it then? But they did. Parliament voted for it. They aren’t stupid people. They know when they are making a mistake. That’s Promethean right there.

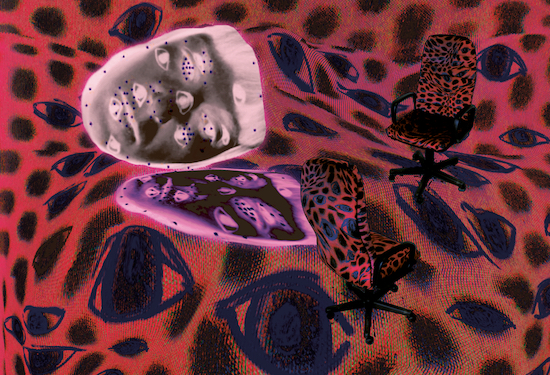

Carla Gannis – Garden of Emoji Delights. Close up. 2014

There’s this legacy that will come from the generation of the internet. What would be an isolated special interest like being a flat earther, are now part of hundreds and thousands of others. There’s a really provocative potential for what that does with history, the dominant model of a singular stream of information has disappeared. What happens to culture long term?

MG: There’s a problem with culture now, it’s ownership is the next battle. Like land ownership, culture is a material itself as well. The future’s battles will not just be through media, it will be cultural ownership of your own identity, jobs, intentions, belief systems. These are all things that can be replaced, by these dominating forces out there. That’s where art has a place. It has its own esoteric mode of being that can’t be owned. It is owned, but when you have groups like ourselves, and peers who are doing stuff like this, it is not completely owned by the wrong people. They are probably very nice people, who don’t think they do anything bad, but what they are doing is feeding a system that is not working and it’s no longer relevant and they’re dependent on it.

The point that exchange happens. If you go somewhere that doesn’t want to invite you or tell you anything about yourself, where does the conversation start? You are reduced to just being a viewer.

MG: That’s what’s important about space, we view it as an interface. What that means is there is a place where you can explore the nature of contemporary things and share difficult questions. Therefore you are not being presented an absolute thing. What’s happening is that you become part of the conversation. This is where the audience comes in, they are part of the art. It’s like the people who came in earlier on – they immediately knew. They were engaged with it, because of the context and the meaning of the show. We are not looking down on people. We are the same. That’s really important because there are people who are in places who have responsibilities to engage who don’t do it. That’s where questions need to be asked regarding their relationships with the world, and their audience and the culture they are supposed to be supporting. Whether they are having a negative effect and just blocking stuff. When really, if you just pulled them out, things would just open up.

There’s that really interesting differential between wanting to educate people, wanting to impose a narrative or wanting to look at exchange.

MG: We want to be educated, by people. We want them to teach us, this is the result of being taught. For instance, I didn’t go to university, but I did work in homeless centres for twelve years in London. That was an education that taught me about how to form relationships with grounded people who we normally wouldn’t meet and without pressuring them, able to have important conversations that can become high aspects of knowledge. We can trigger that off when they don’t feel uncomfortable talking about things in intellectual ways, when they actually don’t realise they are. People gain a focus, and they gain an agency just because their knowledge is allowed to be heard. You tap into their knowledge without imposing your knowledge. That’s the game of play – if there is a game. You have to negotiate a peer relationship where the conversations are ones of equal value to them as they are to us.

Are We All Addicts Now? opens at Furtherfield on 16 September