Some ideas, in retrospect, seem so good, so obvious, so true, that you are amazed it took anyone this long to put them into practice. Since 2005, Frieze Sculpture Park has been populating Regent’s Park’s ‘English Garden’ with strange and wonderful forms in bronze and stone. But always, somewhat perversely, in the dead of winter, when this nicest, leafiest, most homely part of the North London green space is entirely devoid of visitors.

This year, for the first time ever, the organisers have brought the opening forward, from October to July, so the public can make hay with it while the sun shines.

The result is London’s largest outdoor exhibition, responsible for the movement of some ninety tonnes of soil, and the decantation of around fifty tonnes of concrete, in support of a selection of twenty-five works which in the words of curator Claire Lilley, are “by turns beautiful, amusing, and political. I think,” she concluded, “they say much about our times.”

The transfer of Frieze’s annual Regent’s Park sculpture park into the summer months, that time of year when, you know, people actually go to the park, may itself say less about anyone’s sudden brainwave from the department of the screamingly obvious, and more about the esteemed position that the Frieze fair now finds itself in, fifteen years after its inauguration. Back then, as the new Tate director Maria Balshaw put it at the sculpture park’s opening on the fourth, contemporary art was like the fencing in the Olympics – obscure, misunderstood, ill-served by the schedules, and uncared-for by the public. Today, she claimed, stretching the sporting metaphor to the point where it became essentially meaningless to someone like me who has never so much as considered watching anything of the Olympics, contemporary art is more like the athletics. Do people watch athletics? Really? Ok. I’ll take your word for it.

Either way, you can see where she’s coming from. Tate Modern gets more footfall than anything you care to compare it to. And the Frieze fair itself now comes customarily welcomed by the Mayor of London like some visiting dignitary from a strange and slightly exotic land with inexplicably large cash reserves. Sadiq Kahn, this year, declares himself “delighted” that Frieze has deigned to grant the capital an air of being “open to innovation, creativity and to visitors from around the world.”

Claire Lilley got a little closer to my own pleasure in finding these works bathed in the rare shafts of English sunlight when she spoke of her repeated encounters and conversations with a couple from Kuwait who were loitering amongst the paved paths and trimmed shrubberies during the sculptures’ installation. “This is the wondrous thing about sculpture in a public place,” Lilley said. “That you can have those conversations.” The exhibition becomes not just a display of singular treasures, but a site of encounter, a place of trespass and interaction.

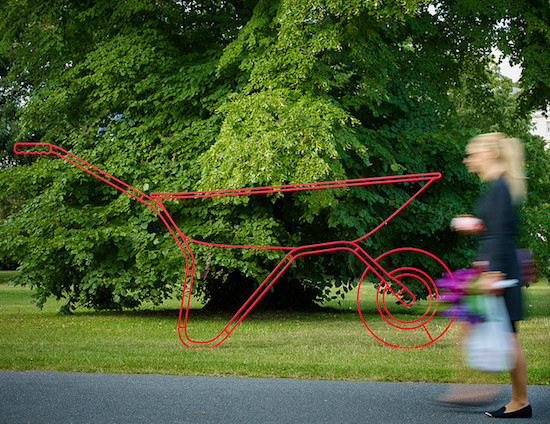

Michael Craig-Martin, Wheelbarrow (red) (2013), New Art Centre / Gagosian, Frieze Sculpture 2017. Photo by Stephen White. Courtesy of Stephen White/Frieze

For there are no invigilators at this show. No stern guards to enforce the little signs requesting the public kindly keep their hands off. And as Mike Pence recently demonstrated so ably, the one thing that literally everyone is inclined – nay, urged, almost obsessively compelled – to do at first sight of a “Do Not Touch” notice, absent any force powerful enough to prevent one’s doing so, is to lay hands on the very thing forbidden to those hands.

Works of art, perhaps more than any other substance bar Critical Space Flight Hardware (pace Pence) and Big Red Buttons, inhabit the very centre of that contradictory and psychologically confounding space in which the tactile is simultaneously teased and frustrated. All those smooth curves and textures, those quasi-sacred surfaces seemingly imbued – like the foot of Montaigne’s statue on the rue des Écoles – with some transmissible germ of genius. Who hasn’t wished, at least once, to lay their fingers on a Frankenthaler, to feel the grain of a Gauguin?

So of course I was jubilant, while lounging on the grass playing Scrabble over the weekend, at the sight of small children in flagrant disregard for the stern signs demanding “Do Not Climb”. Bernar Venet’s 17 Acute Unequal Angles, a tangle of Curten steel triangles like an Emerald City after lights out or a brutalist playground from some sci-fi dystopia, became their very own climbing frame, to be clambered over and tunnelled gleefully under, without qualm, unmolested.

Final Days by Jersey City pop artist KAWS (Brian Donnelly) may make its afrormosia wood Mickey into a kind of zombie, all outstretched arms and exes for eyes. But it still proved friendly enough for the young girls I saw leaping and lolling over its bulbous paws. Even undead, become a marauding spectre of rampant consumer capitalism, the anthropomorphic mouse remains a symbol of goodwill, an invitation to play.

Sir Anthony Cragg, Stroke (2014), Holtermann Fine Art, Frieze Sculpture 2017, Frieze Sculpture 2017. Photo by Stephen White. Courtesy of Stephen White/Frieze

Inviting footplay of another kind – and from an older audience – Hank Willis Thomas’s Endless Column of twenty-two impossibly balanced soccer balls, one atop the other, reaching to the sky. This totemic tower may imply something of the exalted, quasi-religious fervour that sporting personalities inspire in our culture. But in offering to passers-by the chance to pose, with their foot, as if in mid-kick, just touching the bottom-most ball, it grants all a chance to share in some of that glory.

Rasheed Araeen’s Summertime – The Regent’s Park, with its mesh of poster paint oranges and blues, looks like a climbing frame – albeit an unfathomably complex one – but isn’t being used as one. The great concrete plinth holding Reza Aramesh’s Metamorphosis – A Study in Liberation has become a backrest for grass-sitters.

Being one third mirror, it’s unsurprising that Alicja Kwade’s Be-Hide has also become a magnet for selfie-takers. But it works best viewed in passing, while walking by on the path. Only then does its illusion really work, of two identical space-hopper-sized rocks – one stone and one aluminium – metamorphosing insensibly one into the other, like a portal between different realities. Still most of its visitors preferred to face the mirrored surface square-on, all the better to pout beside a bit of art.

Alicja Kwade, Big Be-Hide (2017), kamel mennour, Frieze Sculpture 2017. Photo by Stephen White. Courtesy of Stephen White/Frieze

Michael Craig-Martin’s Wheelbarrow (red), an outline in powder-coated steel acts as a frame for the mighty tree trunk behind it, carrying nature in its hollowed lines. The relation of Ugo Rondinone’s Summer Moon is more ambiguous. This perfect replica of a petrified oak in cast aluminium and white enamel paint casts a chill on its surroundings with its craggy limbs and intimations of the apocalypse.

Regent’s Park’s English Garden was apparently once a hotspot for Pokemon Go players, a site awash with rare shuckles and slugmas. Since criticism of developers Niantic that the game was supposedly leading players to hunt weedles in Auschwitz-Birkenau and Bosnian minefields, there are now fewer stumbling players staring at their phone screens. The closest thing to a Pokemon here today is probably the swollen Barbapapa-like things in pink, turquoise, and gold erected by Takuro Kuwata. But figures like Tony Cragg’s Stroke, a knot of swirling gold like ribbons of molten ginger, or Miquel Barceló’s upturned elephant in patinated bronze (Gran Elephandret) do seem, somehow, like shimmering projections from some other – more virtual – plane of reality. Frieze has definitively weirded the life of the park. This is summer augmented.

Frieze Sculpture 2017 is in Regent’s Park from 5 July to 8 October