I first met Bacon, and even came to enjoy profound and very personal exchanges with him, thanks to Michel Leiris, a mutual friend for whom we both held high regard and great affection. At the time I was preparing to pay tribute to the remarkable writer that Leiris was by dedicating to him a whole volume of my literary and artistic revue L’Ire des vents (The ire of the winds), which I had founded in 1978 and to the first issue of which he had contributed.

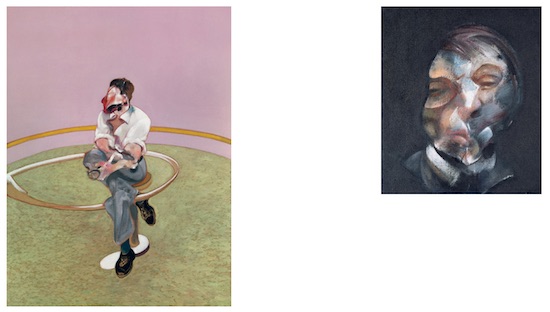

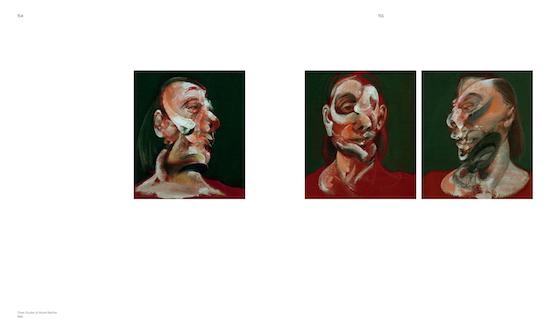

For my project, which appeared in 1981, I had already made contact with Francis Bacon for two reasons. We began with an exchange of letters concerning the two portraits of Leiris that he had made and which I was keen to reproduce. Bacon was very happy to allow them to be published in this celebratory volume and even suggested we should do it in colour, offering to pay the cost of this himself. This was typical of Bacon’s magnificent generosity, his nobility and attentiveness to others.

My second request turned out to be more difficult for him. I wanted him to write a short character portrait of Leiris. While Bacon was comfortable with the format of the interview – he had replied brilliantly to David Sylvester’s questions, and their exchanges were utterly engrossing – he was not a writer. He was hesitant. I insisted. In the end, Bacon took the plunge. He later told me he had originally planned to conduct an interview, but he took a different course entirely. He sent me a short piece comprising two compact paragraphs that he had dictated. The first was more analytical, and touched on Leiris’s style; the second was intensely poetic, evocative of the magic of the undertaking (he wrote: “Despair runs alongside these moments of brightness, and this complicated chain unwinds along the tragic and wonderful tightrope that stretches from birth to death”). He said it all, quite wonderfully. I barely had to edit the text (just very lightly for style), before sending it back to Bacon.

In June 1981, one month after the publication of the revue, I properly made his acquaintance, on the occasion of one of his visits to Paris, at a lunch that brought the three of us together – Leiris, Bacon and me.

It was an exquisite encounter. We met for a drink at Les Deux Magots. Leiris was the first to arrive. His punctuality was legendary: he always arrived in advance of everyone. I was the second to turn up, and we had to wait only a short time until Bacon arrived at our allotted meeting time. We greeted each other warmly, and I immediately felt as if we had known each other for a long time. Bacon was lively and likeable. He looked like an aristocrat and a commoner both at the same time. He had an exceptional delicacy. The other customers around us were staring at him in a somewhat disconcerting way. He was recognised everywhere. His silhouette and his face were well known from a number of very good photographs (Bacon was very photogenic). It didn’t bother him much, or at least he didn’t like to show it if it did.

We left and we went down Rue de Rennes and Rue de Sèvres to end up at Le Récamier, where Leiris had reserved a table. Bacon was very happy to be walking through Paris, which he liked so much (it was his favourite city, as he would always say with passion), and the sun shone on his almost childish delight in breathing the air of the Latin Quarter. It was a pleasant meal, indeed more than that – fortifying, brilliant. We touched on deeper things but moved on, as if there were something in the background that kept everything light and easy. Three’s a crowd, but this lunch was a great success.

We spoke about literature, both English and French (as well as Baudelaire, who was in pole position, we shared the same, far from superficial passions for the likes of John Donne, William Blake and T.S. Eliot); art, both of the past and of the present (Degas was for both of us the towering figure, but we also touched on Van Gogh and Picasso); the most desirable locations (which meant Paris and the Côte d’Azur, not forgetting Lyon, which for Bacon was something of a mystery he somewhat feared); life and the prospects it offered everyone (which turned into a very open, mutual exchange of confidences, especially about Bacon’s youth and his early days as a creative artist).

The lunch stretched on, but in the most convivial of atmospheres, until 5 o’clock, when we finally got up to leave, and Bacon suggested that we might go for a drink somewhere. None of us wanted to break the bond that held us together (as Bacon expressed it in his portrait of Leiris), because life was such that these experiences of plenitude don’t come along too often. We subsequently managed to get together as a threesome on a few more occasions, particularly in 1986 and 1987. However, more personal one-to-one encounters gradually became the norm. That first meeting remains a treasured memory, not least because of the kind courtesy of Michel Leiris, who had been so obliging in bringing us all together.

Bacon was deeply in love with Paris. He had discovered his vocation as a designer and painter there in 1927–28. In 1981, when we first met, he had had a flat in Rue de Birague for seven years (he stayed there ten years in total, until 1984). He held the French people in high esteem and was inordinately fond of France in general. That echoed his refined, aristocratic inclination, with a hint of anarchism for someone strangely attached to the social order. Obviously Bacon had a somewhat idyllic view of France, like many foreigners who have been influenced by French culture, but this was to my benefit, and I realised that because of this our exchanges might have seemed quite precious to him.

He came to Paris regularly; we had agreed that he would inform me by letter and that we would then set up an actual arrangement over the phone. This is how it worked out, and we had many fine meals together in restaurants (Le Dôme was his favourite, or Le Duc for seafood, but we might also end up at Brasserie Lipp, Le Lapérouse, Le Voltaire, Lasserre or another place near the Place des Vosges whose name escapes me now), either in the company of Michel Leiris or just the two of us or with another mutual acquaintance. He was very choosy about what he ate, and he paid attention to the choice of wine and even of mineral water. There were also the grand openings of his exhibitions, as in 1984 and 1987. Even in a large crowd, with people demanding his attention, Bacon was always solicitous to the needs of his friends and carved out moments of calm in the midst of all the hubbub. It was obvious that Bacon was equally as good at withholding as revealing. He didn’t shy away from explaining his destiny, he offered many revealing personal insights, but to some he masked the dark side of his existence, no doubt respectful of the difference he sensed in others.

In appearance Bacon was more complex than was often thought. It wasn’t just because his work contained the odd bits of bloody meat that he seemed to have the physique of a butcher or an abattoir worker. He looked dreamy or surprised; sometimes he would probe you with a rare depth. His eyes, his hair and his features were typically English; he could break the ice simply with his smile. Perhaps he thought it was necessary to counterbalance his natural elegance with a brusque tendency to unmask himself suddenly. He often dressed casually: leather jacket, shoes, watch. He nonetheless possessed a rare refinement which kept the violence that brewed within him at a distance, and directed it against himself.

Emboldened by the courtesy and tolerance Bacon showed towards me, I sometimes managed to question him about certain subjects that intrigued me but which he didn’t much like talking about. I got him to open up about his trips to South Africa, his learning years as a designer; he was the one who moved on to talking about Ireland. I asked him to describe Soho, which to a large extent remained an enigma to me, and he did so, with good grace. He was careful to tone down some of the details. I drew the conclusion that for him it was somewhere he had lived his life intensely, not a place of creativity. He relished the atmosphere. He would shake his head and smile, tender as well as mocking about the circles he frequented, which had given him so much.

It should be pointed out that he was talking about it at several removes: he was in Paris and speaking to a disinterested Frenchman who was simply curious. The pretext for all these digressions was the emblematic painting Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho, for which I was full of praise.

He sketched in the streets, the bars, the restaurants. He waxed lyrical when he described Wheelers, which he never mentioned by name, calling it his favourite fish restaurant (though he might well have said favourite restaurant full stop), and became nostalgic when talking about his friend Muriel Belcher in relation to Isabel Rawsthorne. Afterwards, every time I went to London and walked through Soho, which had changed immeasurably, I thought about Francis Bacon and saw, as if superimposed on the present-day scene, an image of Isabel Rawsthorne caught by surprise at a crossroads, eyes alert to the traffic, testing a shallow puddle with her foot.

Bacon knew how much I liked another of his paintings, which so much evoked that place at that time, Portrait of George Dyer Riding a Bicycle; I told him it was my absolute favourite of all his works because of its technique, the concision of the subject and the fullness of its humanity. He was pleased by my reaction but confided in me that this picture couldn’t be seen any more because it was now owned by a difficult friend with whom he had fallen out (he didn’t mention Lucian Freud by name). I got the feeling he was more saddened than irritated by this privation.

I probed him about his studio in Cromwell Place and why he had left it. He didn’t dodge the question. He told me that he had loved it for its charm and elegance, which he had managed to subvert by the chaos he had created. In his eyes it was the best studio he had ever owned; the others didn’t suit him so well, either because of too much light or too little, except for his present one, in Reece Mews. He was very reserved about foreign places (Tangier, which had turned out to be so catastrophic; Monte Carlo, where nevertheless he had produced some superb series and had immersed himself in the pleasure of inventing; even Paris, where Rue de Birague was more part of his life than of his art). He had only left Cromwell Place after the death of his adored nanny, who was so devoted that she had followed him when he set himself up in Monaco. He had had no desire to remain there, there had been a caesura in his life, he had needed to come to terms with it and explore it in his work, at least in its gestation. He had sought refuge with friends before he managed to dig up (his phrase) Reece Mews, which no one much liked except him. He knew it would be useful for his work, and in this he wasn’t mistaken.

The thing that enthused me the most in our exchanges was when Bacon spoke to me about the way in which he conceived of the act of creation, in terms of both the wider principles and the material applications and vagaries of the process. Bacon was uncompromising in his initial assumptions and very precise on the details and the circumstances. I greatly admired the fact that he had finished off a painting that he had been struggling to complete by violently and angrily hurling paint at it, the impact very evident in the finished picture.

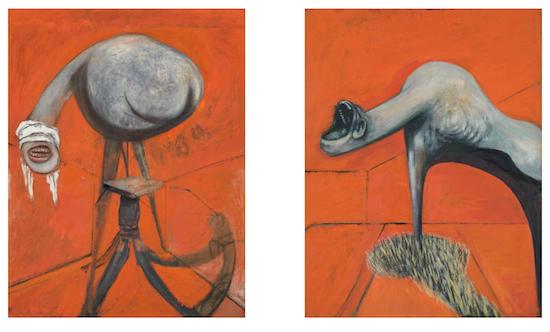

He would smile when he talked about his use of photography. Initially he would turn to Marey and, infinitely more, to Muybridge, one of his constant points of reference, whose studies of movement he considered definitive. They strongly influenced him, but he transformed what they depicted, not only through distortion, but in their very content; thus Muybridge’s two wrestlers became in his painting two men copulating. I’m not sure he would have developed an interest in dogs without Muybridge, given that dog hair brought on his asthma.

He also liked film stills, such as the eyeball-cutting scene in Un chien andalou and the nurse’s scream in Battleship Potemkin. He found the pictures that employed models useful, whether they were elaborated or simple photomatons. Everything had meaning, and he explained astonishingly well the relationship of figures to the background, which he henceforth added at the end (contrary to his earlier period); he was not averse to returning to the geometric structure and the décor. He felt it important that the spectator was convinced that the scenes were not telling a story but suspending a movement, representing singular moments. Nevertheless, there was an allusion to a whole sweep of life or a vision, but according to him that all comes in one block and so did not entail narrative unless combined with the poetic dream. He laughed at his ironies, such as his small-format trompe-l’œil photographs, tacked to the wall as in a studio, but then placed on the painted surface next to the person to whom they gave birth.

We discussed the grain of painting and the tone, comparing the wide, calm spaces of the present with superimposed touches of earlier times. He couldn’t fully account for such an upheaval other than that he perceived the need to proceed in this way. He was always attentive to individual moments, and this was expressed by the urgency of his need to incarnate the most fleeting. There was also a more general pragmatism involved; for example, his maximum size of format was dictated by what could fit through the doors of his studio in Reece Mews: it was impossible to carry anything larger than 147.5 cm by 198 cm (58 × 78 in), at an angle, as it had to be manipulated round the corners of the staircase down to the ground floor. Less prosaically, Bacon had derived an ideal format from this practical stringency, as dealing with reality was for him the ratification of an artistic requirement. I had the whimsical idea that this now marvellous space at Reece Mews (converted former stables like the Mews in New York) took him back to the stables of his childhood in Dublin. They had been built in the same era as the one in which he elaborated a major body of work. I shared my idea with him and he shook his head, smiling and trying to come up with a plausible alternative explanation.

Sometimes Bacon would reveal part of his unease. Generally speaking, he was not at all satisfied with his work. It was a little as if he always aimed at the impossible and failed every time. A moving target, always slipping out of sight. When Bacon talked about it he usually started off by complaining, but eventually found his way to humour and acceptance. On many occasions he told me of his fear that he would not be able to achieve his aim. I wasn’t the best judge, but recently he had brought off some remarkable works, surely he couldn’t deny that? He conceded that some of his pictures weren’t too bad, inhabited by their own bright necessity. It was clear that a given composition that might be singularly incisive cast into the shadows two or three others that were not very honest. We had never before seen an artist produce such a continuous stream of paintings destined to turn history upside down. That was the case with him, but his protest was of a different order: even while creating his greatest successes at some point he was plunged into perplexity, he wanted to destroy everything, and so his dealers made it their duty to bag his paintings quickly, undoubtedly to rescue them from his vengeful and masochistic dissatisfaction. After a while, he was able to accept this.

A long time after Bacon died, I read some books that said that he could be nasty and cruel, in a word unforgiving, to his closest friends among his Soho set. To be honest, this Bacon was completely unknown to me. At first sight it seems more in tune with his paintings, but in his dealings with his intellectual friends in Paris he never adopted such an attitude. I didn’t see any sign of excess other than an inner turmoil that he found it difficult to repress but which could calm down over the course of a long story told in confidence (he was still likely to erupt, though). Francis Bacon was the soul of attentiveness, he was generous in all matters, he brought a delicious gentleness to his relationships. I realised that his night-time world was the opposite of his daytime world. I was aware how lucky I was.

Francis Bacon always accompanied me on my return visits to the pictorial twentieth century, or at least my twentieth century. I was grateful to him above all for having communicated to me a depth of experience in life and art. I, who was neither a homosexual, nor a drinker, nor a gambler, was on the same level with his work, which showed that, beginning from a singular experience, it had achieved an undeniable unanimity, by stripping everything away and digging deeper. Bacon, by trying to break down forms and set his materials in play, had formulated the most exact fiction of human existence, all of this assembled round a distortion of the body, a scream, with a daring gnashing of the teeth. I was once more able to see his smile, his dancing walk; I could hear his melodious words. He was so generous, so attentive to others that, in the full flow of conversation, it never crossed your mind for a moment that you were in the presence of an artist of such indisputable stature that he was a paradigm. Francis Bacon remained very present. He would be ever present, at least for me – a beacon guiding us towards a point of view or, as Rimbaud put it, towards a way of seeing.

Francis Bacon, or The Measure of Excess by Vyes Peyré is published by ACC Art Books