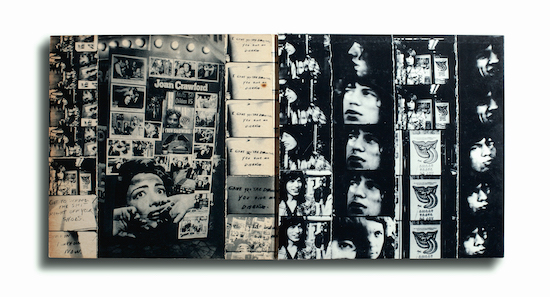

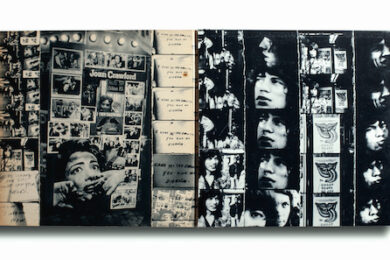

Vinyl: The Rolling Stones, Exile On Main Street, Rolling Stones Records – COC 6910, England, 1972. Photography: Robert Frank ; Design: John Van Hamersveld/Norman Sieff

“In the very beginning, I was hanging books on the walls like art pieces,” explains Antoine de Beaupré over email. “I realised that sometimes people were looking at me in a strange way. I then started to swap the books with records and suddenly a lot of ideas arose.” De Beaupré is a book dealer, publisher, and curator. Librairie 213, his Parisian bookshop, specialises in rare and out-of-print photography books. His primary passion, however, has always been music. “I started to buy my first records as a teenager in the mid-80s. LPs were cheap because CDs were taking over. I became a collector without realising it!”

This month, For The Record: Photography & The Art Of The Album Cover opens at The Photographers’ Gallery in London. The show utilises de Beaupré’s extensive record collection as an opportunity to explore the interrelationship of photography and music as manifested in the medium of the album cover. The show is composed of many iconic and some lesser known LPs displayed in plexiglass frames. The covers are grouped by themes, which closely follow the structure of Total Records, a catalogue of the original exhibition (co-curated by de Beaupré, Serge Vincendet and Sam Stourdzé) held at the Rencontres d’Arles, France, in 2015.

There is an evident attempt to redress the narrative, where the musicians take centre stage, by giving equal credit to the photographers and graphic designers responsible for visualising the music. Aside from Andy Warhol’s infamous banana, which donned the cover of The Velvet Underground & Nico, and Hipgnosis’s conceptual photo shoots that communicated the epic nature of bands like Pink Floyd, there are more obscure covers on display. A collection of “race records”, which were created for African American consumption, are noteworthy not only for the music they documented, but also for their depiction of a segregated United States. Records released by labels Yazoo and Riverside portrayed the daily lives of communities stigmatised by institutional racism, as shot by Dorothea Lange and Jack Delano, while Bluesville prominently featured blues legends from the Mississippi Delta on its covers.

A small section of the exhibition is dedicated to visual artists who utilised the record as an extension of their practice. These limited edition pressings include documentation of a Joseph Beuys performance, a lecture on happenings by Allan Kaprow as well as Misch-U. Trennkunst, an experimental spoken word release by Dieter Roth and Arnulf Rainer. ‘Transartistic’, the chapter dedicated to the same theme in Total Records, includes many other works, such as Harry Bertoia’s Sonambient series. It’s understandable that the curators chose not to dedicate more gallery space to these works – mainstream concerns are much more likely to draw the crowds – but it’s a pity nevertheless.

Vinyl: Diana Ross, Silk Electric, RCA – AFL1-4384, New York, USA, 1982.Photography & Design: Andy Warhol

Jazz is shown to be responsible for influencing both the way that photographers approached their subjects and the aesthetics of album cover design. Lee Friedlander, who is best known for his urban social landscapes, launched his career working for Atlantic Records. Friedlander’s enigmatic portrait of Miles Davis for In A Silent Way, released by Columbia in 1969, is displayed here alongside photos of Ray Charles and Ornette Coleman. It is said in the curators’ notes that jazz taught the young Friedlander a sense of improvisation. Although this isn’t evident on these particular LPs, the sense of freedom that jazz evokes can be seen on releases by ESP-Disk. You can practically hear the saxophone skronk when looking at Sandra H. Stollman’s double exposure portrait of Albert Ayler (Spirits Rejoice, 1965), while the same photographer poses Sonny Simmons, on a rock in New York’s Central Park, to resemble a monument to self-expression (Staying On The Watch, 1966).

Blue Note’s visual identity is well documented and it’s always a pleasure to view these covers up close. The catalogue for the original exhibition shows the photographs as they appear on the albums alongside the uncropped originals. Considering Blue Note’s famed attention to detail, it’s a shame that the original prints are not displayed here, only the records. In order to dive deeper into the story behind the images you have to buy the book.

Thankfully, a series of prints by Linda McCartney allows the public to make a comparison between the moment as it was captured, and the final product. Iain Macmillan’s portrait of The Beatles for Abbey Road is woven into our cultural fabric to such a degree that copycat covers have become a cliché. This is best exemplified by the nearly naked Red Hot Chili Peppers crossing the same street with socks on their cocks (The Abbey Road E.P., 1988; not on display). McCartney’s behind the scenes shots, however, show The Beatles as human beings grown tired of their iconic status, but willing to play along one final time. A shot of a passer-by talking to Ringo Starr, while the rest of the band waits to cross, is touching.

Vinyl: Grace Jones, Island Life, Island Records – 207 472, France, 1985.Photography: Jean-Paul Goude ; Design: Greg Porto

Another highlight is a wall dedicated to political records. Some releases use sound as propaganda, such as Mai-68, a 7” that features field recordings made on the barricades during the May 1968 uprisings in Paris. Others, like Rage Against The Machine’s eponymous debut, co-opt the image of revolt (in this case Malcolm Browne’s Pulitzer-winning photograph of Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation) to align themselves with an anti-establishment ideology.

The adjacent wall shows albums that have fallen victim to censorship. This is a potentially excellent case study that could have been better realised. Out of a handful of examples, only two censored albums sit alongside their uncensored siblings: Beggars Banquet by The Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland. A graffitied toilet, shot by Barry Feinstein, was initially rejected by the Stones’ label in favour of a mediocre typographic cover, while Jimi Hendrix himself disapproved of David Montgomery’s photograph of nineteen nude women lounging against a black background. The image was still used for the UK release of Electric Ladyland, but the album was sold in brown paper bags by retailers.

Despite some flaws, For The Record challenges the idiom that a book shouldn’t be judged by its cover. This notion is problematic, because it assumes that design is subordinate to the content inside. Even if a well-designed book jacket doesn’t reflect the prose, at least you still have a great cover to look at – Germano Facetti’s design direction for Penguin being a case in point. The same goes for records. Before streaming, the cover would be your first connection to the music and, for many photographers, shooting covers was an additional platform for their craft, replete with its own set of nuances.

The way in which many of us consume music may have changed, but the album cover remains an essential conduit between artist and listener. Antoine de Beaupré agrees: “From my perspective, great covers shine through [with] their visual language or the esthétisme established by the record labels. We all have a relationship with vinyl. What I did was to contextualise a popular object, to see it in a different way. When you walk out of the show, you may stop in a record shop and buy a record, just for the cover, and put it on your wall.”

For The Record: Photography & The Art Of The Album Cover will be on display at The Photographers’ Gallery, London from 8 April until 12 June 2022.