Eric Ravilious died in 1942 when the air sea rescue flight he’d opted to join in his role as a war artist disappeared without trace off the coast of Iceland. Despite his own life being cut short so dramatically at the age of thirty-nine, his ideas and aesthetic sensibilities – you could broadly call it mid-century British modernism – continued through the work of his friends, lovers, collaborators and associates for decades after. This gravitational pull that Ravilious held over British art for years after his death is the subject of The Pattern of Friendship, a touring exhibition from the Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne where the artist was born (and which he would later call “a bad dream… like the ruins of Pompeii.”)

These continuing strands of the British artist’s life encompass the work of Paul and John Nash, fellow war artists with angular, semi-abstract styles not too dissimilar to Ravilious’s own. Given that the art world at the time was dominated by men even more than it is today, it’s a cheering surprise that so many women artists are included in this overview, among them designers Enid Marx and Peggy Angus, painters Tirzah Garwood and Diana Low, and printmaker Helen Binyon. One takeaway point from the exhibition is that at that time women were more likely to enjoy successful careers as designers or illustrators than as fine artists. The second takeaway point is that by that time these genre distinctions had become effectively meaningless.

The exhibition starts by detailing the group’s formation at the Royal College of Art where Ravilious was teaching, running through their formative dabblings in different styles and mediums. The dizzyingly geometric Pattern Paper Designs (1930-33) of Tirzah Garwood are an early highlight, with repeating proto-modernist motifs that take inspiration from the shapes of cells, seeds and other molecular forms. Similarly dazzling is Enid Marx’s 1923 sketchbook of complex, angular patterns.

The group’s extensive illustration work for publishers including Penguin and Faber & Faber is neatly showcased inside a mock-up bookstore within the exhibition, with the satisfying cover designs of Edward Bawden standing out in particular. His design for R.M. Lucey’s forgotten A Problem A Day is borderline surrealist and his cover for Faber & Gwyer’s Long Lance of 1928 (“The Autobiography of a Blackfoot Indian Chief”) neatly balances the triangular forms of tipis, pine trees, and mountains in the background to give an evocative sense of place. Even more lucid is his 1948 cover for Saul Bellow’s The Victim, a film noir design using the typography of a Hitchcock horror. This is art for a purpose, art making itself useful.

Phyllis Bliss, Portrait of Eric Ravilious, c. 1929. © Prudence and Rosalind Bliss

As with other artistic movements of the twenties and thirties there are hints and indications of what is to come, a war which would be documented in harrowing detail by both Nash brothers in some of their most celebrated paintings. Particularly startling is Enid Marx’s cover design for Margeret Lambert’s The Saar (1934), a book that analysed Adolf Hitler’s future territorial ambitions in Europe, named after a disputed territory on the France-Germany border. Even more surprising than a woman designing a cover for a book written by another woman is the back cover, which simply places a stark question mark between four swastikas, while the front cover shows three industrial chimneys in a style playing on Soviet constructivism. The group’s days of sunshine soaked optimism, as captured in paintings such as Ravilious’s Newhaven Harbour of 1937, were coming to an end.

If the group were collectively working towards establishing their own shade of modernism in the visual arts, it was never intended to be the truly radical ‘break from the past’ of their contemporaries in Russia and at the Bauhaus. Commissioned to design the guidebook covers for British Pavilions at world expos in 1937 and 1939, Ravilious’s satisfying but ultimately conservative designs – incorporating the royal coat of arms above some funky lettering – demonstrate that this branch of pastel-shade modernism was one that was palatable to the establishment.

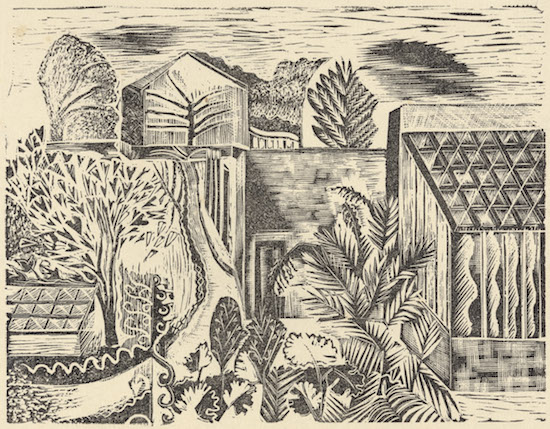

Enid Marx, Back Garden, c. 1923. © Estate of Enid Marx

Despite this a few moments of radicalism do break through the style’s inherent cosiness, particularly in the work of both Nash brothers. Wood engravings by Paul Nash designed to illustrate a 1925 book on Wagner’s Ring Cycle are expressive in the extreme, depicting massive jagged forms that look like a modern day Daniel Libeskind building. It’s a world away from the commission work both brothers did for the improbably named Empire Marketing Board, which existed to flog the produce of the waning British empire on home soil. Paul Nash’s work shows baskets of fresh fruit and vegetables in front of a sunlit greenhouse, while John Nash’s work for the ad-man’s shilling depicts an idyllic fruit orchard.

The exhibition culminates with the Second World War, where two of the Ravilious set would be killed while documenting the carnage. Eric’s paintings while working as a recognised war artist depict the isolation of the naval excursions that he attached himself to, in pictures such as the lonely Norway (1940) and his luminous snapshot of HMS Ark Royal In Action (1940). Other paintings such as Drift Boat and Coastal Defences show the effects of war – or the preparation for war – on the British landscape. In 15 Inch Gun Turret (1942), Barnett Freedman – who would survive the war – paints a weapon with a cross-section cut out, allowing us to see the loading mechanism inside in painstaking detail, as if from an old copy of Popular Mechanics. The broad-framed boys tending to the gun turret would lose their lives a few months later when HMS Repulse was sunk by Japanese forces – many of the war pictures here show ships or aircraft that would be lost soon after being painted.

The show ends with a chilling artefact: a camp logbook which records Ravilious’s last flight and his failure to return, the final page marked by an RAF stamp with “DEATH PRESUMED” picked out in blue capital letters. Sellotaped below the doomed flight’s details is a cutting of a poem titled Goodbye, which speaks of “the agony of life’s sweet ecstasy.” It’s this ineffable lust for life that is captured in the preceding two decades of work by Eric Ravilious and his friends, who created paintings, designs, furniture, pattern paper, book covers, woodcarvings, and illustrations that radiate what Ewan MacColl called the joy of living.

Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship – English Artist Designers 1922 to 1942 is at Sheffield Millennium Gallery until 7 January 2018