Credit: Emma Smith, 5Hz (2018) PHOTO: Reece Straw

Emma Smith’s 5hz was an exhibition that was initially challenging for me. The first coming aesthetically, it reminded me of a very specific British Heart Foundation shop in Aberdeen, selling a variety of disused wooden furniture. Armoires, sideboards, curio cabinets, etc. built sturdy and to last, almost to a fault. The polished wood furniture languished on the shop floor in various states of decomposition, gradually being reduced in price and slowly finding its way closer to the skip – broken up with sledgehammers at the back of the store.

It’s this type of furniture that populates the installation of 5hz, and the first thing that you notice as a viewer is the clash between this aesthetic and the audio installation, a language created by the artist (in conjunction with researchers) as a system of sung communication. This distinction is important because 5hz is not an exhibition of immediacy; it’s one that unfolds with the viewer’s impetus to learn.

When I entered the gallery, there were two other people present: a mother and an infant. I’d been there less than five minutes when the mother approached one of the pieces of furniture (a record player console) and started playing an album by the Cocteau Twins. The stack of records Smith had chosen consisted of a collection of contemporary music that all makes use of constructed languages. This points to something 5hz does very well: eases the viewer into the mode of thinking required to understand what it is trying to do. The personal, emotional response that hearing Cocteau Twins songs playing in that space created was the push that I needed to want to better understand the idea of a wordless sonic communication.

We are able to interpret and experience feelings from these songs, we’re able to build relationships with them and perhaps to do so more easily because they are presented within the context of music. So why would we not be able to interpret sounds or communicate using a distillation of language? A wordless system? The records are a really fantastic way of opening up the concept for the viewer as well as creating a relaxed atmosphere in the space, aiding learning and understanding non-verbally.

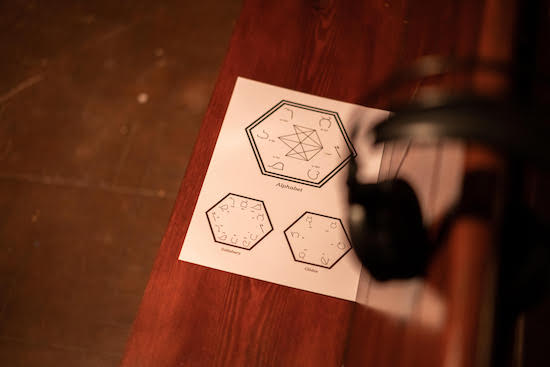

I almost wanted to just sit and enjoy the experience of listening to the records and looking at the furniture, walking around the gallery and letting my mind wander in the ephemera, but Smith offers the opportunity to learn this communication system, with a promise that you can pick it up in less than fifteen minutes. What kind of viewer would I be not to at least try? Sitting on pews inside a hexagonal structure, awaiting a viewer to engage them, headphones sit in place of teachers. The language is explained via a looped recording and the listener is asked to participate in the lessons, making sounds of their own.

This is, in my opinion, where 5hz becomes a very impressive piece of work. The years of research, workshops, and study that went into producing this project are made visible by the varied ways in which the installation communicates with the viewer. Whilst learning the language, we become conscious of what language actually does. The functionality of language as a communicative device and what the necessities of communication actually are. Especially when, in a field like contemporary art, language can often become obtuse and needlessly complicated, seeing a work that aimed to function as a sort of communicative unifier was something I found very interesting. The position of paralinguistic communication is particularly interesting within a contemporary context in that it is antithetical to how blunted digital communication can be. This language functions in a very personal, collaborative way – something that feels like a reaction to digital, bureaucratic or societal barriers.

For an interactive work of art hinging on the creation and use of a sung language, 5hz is very subtle. It’s subtle in the way that it unravels complexities and encourages the viewer to consider them, without ever bringing them clearly into the light. One of the strengths of this installation is the way in which it doesn’t need to be didactic, in spite of literally consisting partly of a process of learning and teaching. It provides the viewer with the tools to more broadly consider the composition of things that are taken for granted – like language. The expressive nature of human beings and to what extent the words that we’re saying actually define our communications. It’s something that, in a world of so many words, we rarely consider – how our aural perception is defined by the physicality of sonic interaction.

With this aspect completely lost in non-physical interaction, it made me think of how we interact online. The many ways in which verbal communication is distilled in digital space differently from IRL interactions and how that might contribute to the large-scale economisation and exploitation of outrage by media outlets. The fact that having communication distilled to only words is taking a great deal away from the communicative experience – something to think about for someone punching these words into a laptop in silence.

Emma Smith, 5hz, is at Primary, Nottingham, until 9 Feb