Whisky? A free nip of whisky? Wait. Run that past me again: a dram as part of an artwork? You’re telling me this kindly pair of Scandinavian artists is offering a glass of Teacher’s, a tot of best-blended Scotch… to a critic? Your Glaswegian reviewer? Shurely shome mishtake.

Teacher’s mind you, but still.

I think I was supposed to wait for the gallery staff to pour me a measure but I’d already swooped down, unscrewed the bottle, and helped myself by the time they arrived. This is part of a work called The Bottle and the Book (2015) where you sit at a desk and have a sneaky peek through a private journal written by the duo whilst draining a relaxing glass of Highland uisge-beatha. And it is fair to say that this strategy is successful. I’m very biased towards this show.

Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset work as a collaborative unit and this is their first survey in the UK. They major in sculptural interventions that have a quicksilver wit. Their gags might appear sweet at first taste but then there’s the burn, the deeper notes having a bite as lingeringly earthy as a peaty Islay malt.

The first work here stuns – The Whitechapel Pool (2018) – where they have transformed the gallery space into an abandoned public swimming bath. There are piles of dirt here and there, the odd leaf, a strip lamp has fallen into the dry basin of the blue-tiled hollow. The metaphor is simple but effective – this is the state of public amenities in Britain now, deliberately run-down, abandoned, trashed. Public services no longer valued. A fictional history of the space jokes about how David Hockney took inspiration from its rippling waters, that it is about to be converted into a boutique hotel for the select.

Scattered on the perimeter of the pool are other works such as the bronze sculpture of an old leather car seat – I must make amends (2018). The title rings a bell and then you connect – it’s from Janis Joplin’s 1970 song ‘Mercedes Benz’ that said car company domesticated, co-opted, in an advert: the classic advanced capitalist consumer move.

A door leads to a changing room – or does it? There are two handles: which one to grab? This is another work, Changing Room/Powerless Structures, Fig. 128 (2018), a portal to nowhere that makes it unclear which gender it was designed for. Ambiguity is key to Elmgreen and Dragset’s practice – easy readings are seemingly embraced only to be subverted in a blink.

Halfway up the stairs to the chapel-like space on the first floor there’s Donation Box (2006), a dysfunctional glass case containing stuff that hints at Britain’s current state of uncomfortable flux – flyers for Brexit, an old military medal, broken Oyster cards. Whatever is the opposite of the Danish concept of hygge this is it. You suspect Elmgreen and Dragset were not averse to getting the first flight out of the UK.

We then meet the first human sculptural forms. These have something of George Segal’s mute sadness about them, ghostly figures who find themselves amidst a melancholic calm like that of a Vilhelm Hammershøi interior, all muted colour and repression.

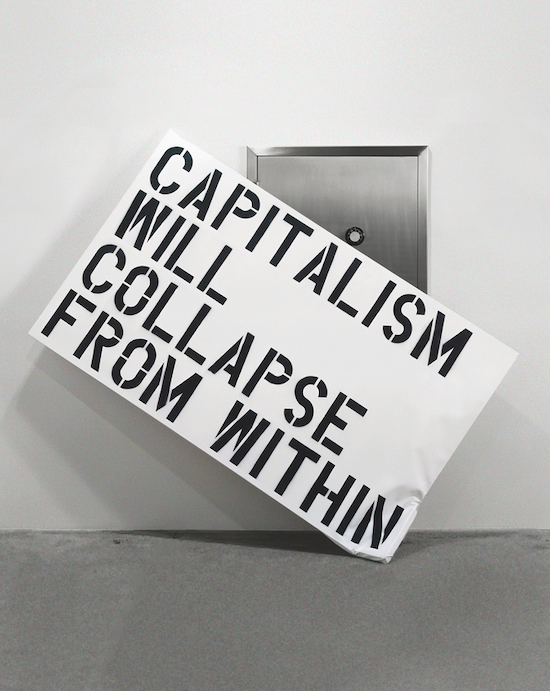

A sleeping baby lies on the floor tucked into a carrier. This is Modern Moses (2006), the bairn is dumped underneath an ATM like so many of our tragic homeless stuck on the streets today. This is the fate of tomorrow’s child – not awaiting God’s instructions like his Biblical forebear but ever delusional of a financial windfall. Given the way the world is going this latter outcome is unlikely. Perhaps a more plausible scenario, in the words of one of their other works here, is that Capitalism Will Collapse From Within (2003).

The next sculpture, One Day (2015), shows another child, a boy, peering up at a display case that holds a rifle, soon to be theirs. Hard not to read this work as a comment on modern America given the near daily accounts of mass shootings over there. The title is good: one day they will be able to take the weapon down, go out on the range and press the trigger. And one day too they will kill. Kill an animal, kill other people or, as we are perhaps encouraged to speculate, kill themselves.

But maybe the kid is a more retiring sort, the type to hide away under the mantelpiece, as with Invisible (2017), where we see a crouching figure shirking, trying to vanish. Faced with nightmare events like this year’s Parkland school massacre who can blame them?

Elmgreen and Dragset are themselves all too aware of their own corporeal transience, their fleeting presence on the planet. In Portrait of the Artists (2018) we see the imprint on a wall where we assume two (imaginary of course) paintings once hung. This act of self-negation is also ambiguous; it could be seen as a modest gesture but at the same time one of self-aggrandizement that says we are so well known that you know who we are without our image even being there. Another invisible self-portrait is Untitled (2014), a bronze of two white pillows side-by-side bearing the indentation of heads in a respectful nod to the late Félix Gonzáles-Torres and his own untitled paired billboard images of unoccupied beds that referenced the AIDS crisis.

There is hope perhaps with the last work here, Pregnant White Maid (2017), a figure as still as those in a Vermeer whose future son or daughter may escape servitude. But Elmgreen and Dragset are adept at setting traps for the unwary, as with Emerging (2018), one of their works that imagines the critic as a bronze vulture hovering over the nest of creativity. They’re surely right to see us as scavengers, a kettle of bald headed beasts that glide around in the hope of downing another malt. Slainte!

Elmgreen & Dragset, This is How We Bite Our Tongue, is at the Whitechapel Gallery until 13 January 2019