A few weeks ago, at an exhibition opening on the other side of London, I found myself talking to one of the artists whose work is prominently featured in Electronic Superhighway, the Whitechapel Gallery’s big new survey of digital and new media art. He expressed a certain trepidation about his impending first visit to the show the next day. Why so? I asked. “Because,” he explained, “it’s the biggest listicle ever!”

I can’t remember exactly how we had got on to the subject of listicles but, to be fair, his comment was not entirely apropos of nothing. I may have, just before, suggested that perhaps F.T. Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto – even the Ten Commandments – might productively be considered as significant pre-internet examples, what the members of Oulipo used to refer to as “anticipatory plagiarism”. Still, when you walk into a show that opens with a massive arsehole talking in text speak and proceeds, therefrom, at an undimmed level of brash, attention-grabbing excitement, it’s hard to escape the feeling of being grabbed by something like the IRL equivalent of clickbait.

The ineluctable seepage of phenomena native to the virtual world through the increasingly permeable barrier of the screen and into physical reality is in many what this show is all about (the ground floor at least). In his 2013 novel Bleeding Edge, Thomas Pynchon referred to this as “virtuality creep”, a kind of “overflow out into the perilous gulf between screen and face … counterfactual elements … popping up like li’l goombas.” But some years before that, several artists had hit upon a word to describe their own practice and that of their peers that amounted to pretty much the same thing. They called it ‘post-internet’.

In a December 30 2009 post from his blog ‘Post Internet’, reprinted in the book Mass Effect (co-edited by Ed Halter, a member of the advisory panel for the Whitechapel show), Gene McHugh writes:

"Four ways that one can talk about ‘postinternet’:

- New media art made after the launch of the world wide web, and thus, the introduction of mainstream culture to the internet.

- Marisa Olson’s definition: Art made after one’s use of the internet. ‘The yield’ of her surfing and computer use, as she describes it.

- Art responding to a condition that may also be described as ‘postinternet’ – when the internet is less a novelty and more a banality.

- What Guthrie Lonergan described as ‘internet aware’ – or when the photo of the art object is more widely dispersed than the object itself."

Over the past couple of years, the term “post-internet art” has gathered a fair amount of stick for the implication that we had somehow moved beyond the internet – as if the internet had happened, done its thing, and gone away already. Morgan Quaintance, for instance, writing in last June’s Art Monthly, criticised post-internet artists for their acquiescence to an ideology expressed by Google chairman Eric Schmidt at the Davos World Economic Forum in terms of an internet on the verge of disappearing. “There will be so many IP addresses,” Schmidt claimed, “so many devices, sensors, things that you are wearing, things that you are interacting with that you won’t even sense it. It will be part of your presence all the time.”

But ‘post-internet’ was never about the end of the internet, just like post-modernism was never about the end of modernism. Once the tropes of modernism were so widespread that they were part of the daily language employed by every Madison Avenue creative, it became absurd to claim for them any radical, oppositional force. But you could at least draw attention to the debasement of modernism by treating it like any other pop cult vernacular. Likewise, as capitalism becomes increasingly dominated by global near-monopolies started by hackers and coders who have proved to be just as rapacious and exploitative as any other multinational enterprise, it becomes absurd to claim hacking and coding as in-themselves radical, oppositional strategies.

While back in 1997 the artist duo MTAA could draw a ‘Simple Net Art Diagram’ showing two computers with a wire between them and a flickering lightning flash in the middle of that wire captioned “The art happens here”, since then things have got a little bit more complicated. Where, for instance, does the “art happen” in a piece like Jonas Lund’s VIP (Viewer Improved Painting), a work which uses a gaze-tracking camera to adjust its amorphous whirl of colours to what its own analysis determines to be the spectator’s own preferences? On the screen? In front of the screen? Behind the screen? Or somewhere else entirely?

Electronic Superhighway 2016 – 1966 (2016). Installation view. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery, London

The place of art is key here. As McHugh put it in another Post Internet blog post (this one from 13 January 2010), “If you were not acquainted with Cory Arcangel as an artist and you came across his YouTube video of of U2’s ‘With or Without You’ mashed up with footage of the Berlin Wall coming down, it would read as a ‘normal’ YouTube video. It seems like something that is native to YouTube and not to art.” Arcangel’s Snowbunny/Lakes, a 70 inch flatscreen bearing an image of Paris Hilton skiing in Aspen, Colorado, manipulated by a Javascript ripple effect, is one of many works presented with their screens turned round 90 degrees to a portrait orientation, like mobile phone screens puffed up and placed on a gallery wall.

A great deal of the work dubbed ‘post-internet’ can be read as a series of strategies in answer to a question not unlike that posed by Marcel Duchamp’s readymades: what happens when you take this stuff off the net and put it in a gallery? Evan Roth’s Internet Cache Self Portrait is pretty much just that: a vast overlapping scroll of images spilling off the wall, taken from Google Maps, eBay, Instagram, and Ted Talks, reflecting his accumulated surfing over a finite period of time. There is a notable lack of porn. Make of that what you will.

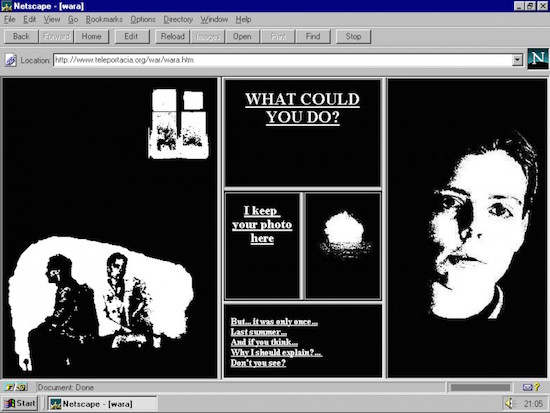

Take a walk up the stairs and Electronic Superhighway soon departs from the kind of personal histories offered by Roth into a more general history of digital and new media art. As an attempt at contextualisation, however, at first glance, the desktops and greying monitors assembled here with their flickering scroll bars and green on black text look as alien from the high gloss glimpsed downstairs as old dinosaur bones. Whether out of a festishistic attention to period fidelity or some kind of deliberate technological verfremdungseffekt, Olia Lialina’s classic net art work of 1996, My Boyfriend Came Back From the War is presented on an old beige Compaq running Netscape Navigator.

If you can get over the weirdness of using such a clunky old interface though, Lialina’s engrossing piece of browser-based storytelling still has the power to suggest new worlds and new kinds of narrative; avenues opened up by the web that remain under-explored and peculiarly thrilling twenty years later. If Electronic Superhighway can, indeed, sometimes feel a little like 247 Times Technology Totally Change The Art World, then perhaps My Boyfriend Came Back From The War is the parenthetical Number 162 that will Definitely Blow Your Mind.

Electronic Superhighway is at the Whitechapel Gallery until 15 May. The book Mass Effect is released by MIT Press