DOT.ART examines digital space and our rights within it through selected net art projects taken from the 1990s to the internet 2.0. Programmed by the pseudo-corporate, nomadic entity that is Ryan Hughes’ Office for Art, Design and Technology, the exhibition explores how projects that are housed and distributed on digital platforms can manifest in real time within the gallery.

Works by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, Heath Bunting, MTAA, Rafaël Rozendaal, Critical Art Ensemble, Lorna Mills, and Ryder Ripps that question online and IRL spaces are collaged and juxtaposed to form new connections. Running concurrently to the exhibition is the staging of their various hyperlinks on Vivid’s website. This folding and unfolding of online and offline has been further expanded through performance, conversations, talks, and a series of readings that take place throughout the show. These events are integral to focus the potential that the gallery has to be an engaged space for commonality and sharing.

DOT.ART contextualises the shift that has taken place in our culture, whereby the practices and languages of online spaces and platforms have become our prevalent means of communication and daily encounter. Yet these spaces are not fixed. They shift and fragment, lying vulnerable to state and corporate interference. Our digital acts are policed as are our physical acts. We now constitute both a physical and a data body.

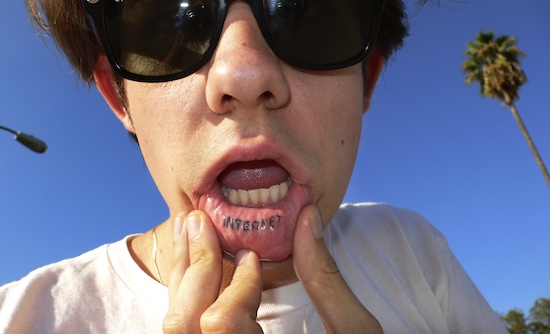

The exhibition opened with a physical performance of Ryder Ripps’ Howl_2.0, a reformatting of Ginsberg’s sprawling countercultural epic for an age of frenzied Tumblr posts and YouTube uploads. Here, the best minds of a generation are now being destroyed by “contemplating gifs”, conversing “about LOL Cats”, and lounging “hungry and lonesome through Gawker”. Howl 2.0 right clicks and refreshes Ginsberg for an impatient 21C, a time where we jump from Uber to Facebook to Just Eat, our movements tracked by the apps that serve us. It provides an accompaniment in our quest to “recreate the syntax and measure of poor Google searches”. Ripps is “with you on the internet”.

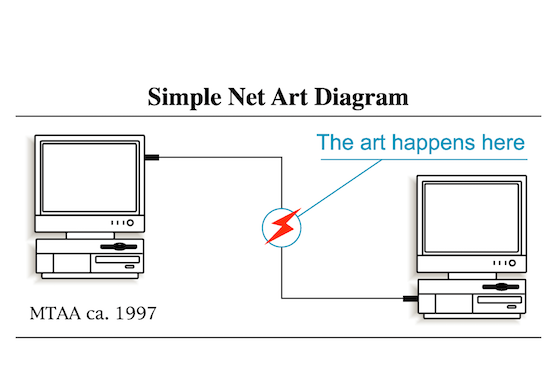

The work focuses on the spaces that we create through online interactions, how we move from being a consumer to a producer, a viewer to the viewed. As you walk into Vivid, you are greeted by a projected jpeg of MTAA’s Simple Net Art Diagram (1997), a work accessible for use under Creative Commons License. The simplicity of the image belies its history as a work that contextualised net art at a time when museums and galleries had little knowledge or awareness of how to approach the medium.

A0 prints of works by Critical Art Ensemble line the walls of the gallery forming a repeated pattern onto which other works are displayed and hung. On one poster, the work Welcome to a World Without Borders (1998) outlines the effect of global corporations in territorialising the free space of the web. The work charts and outlines the systematic locking of the user into an inflexible platform, one that promises an illusion of unbounded space. The only impermanence here is time – the citation of IBM, Samsung, Motorola, The Disney Channel, and Sony could now morph seamlessly into Google, EE, Instagram, Apple, and Netflix and feel just as indistinguishable as any physical high street in Europe.

In the other poster, By Any Media Necessary (2008), a citizen walks through busy a public space with a placard that rephrases Malcolm X’s speech given to the Organization of Afro-American Unity founding rally on June 28, 1964. speech for the present day. The power that a single voice has is poignant here: we are acknowledged, our suspicions echoed back with a wry smile. Nearby, texts by Critical Art Ensemble have been gathered in a vitrine, separated from us by glass, stilled inaccessible objects. It’s a reminder of the ways in which material objects are still privileged over digital files. The Office for Art, Design and Technology has sought ways to breathe life into these documents. Critical Art Ensemble’s text Slacker Luddites has been read and discussed through a group reading. This and other opportunities sought to further engage the deep complexities at play in this show through collective conversation within the context of the exhibition.

This potential for free access to space is focussed through BorderXing Guide (2002), in which Heath Bunting eschewed electronic media to concentrate on physical landmass. The work is presented through a series of digital photos and the project’s website. The images are innocuous snapshots taken during transit. Where they are photographed is revealed only through further engagement with the website. At Vivid, you walk into an enclosed space to access it. If you are familiar with the project you have the means to understand its function and what its open placement on the web represents. The site documents a series of border crossings undertaken by the artist and other participants during the early twenty-first century. The project documents and explores the feasibility of undertaking specific routes without papers.

Some of these crossings are benign. One of the routes documents walking out a Monte Carlo train station through a carpark and then into France for a picnic. Other itineraries document journeys that are navigated through hellish layers of surveillance, restriction, and endurance – places where it is preferable not to be human, where Bunting moves under foliage to avoid surveillance, undertakes obscure routes so that he is not seen.

The closer Heath gets to the permeability of a closed border; the harder his route becomes. In places it falls into impossibility. The website states in one of its entries that “BorderXing is sometimes beautiful, sometimes not”. BorderXing Guide constitutes work undertaken as artwork and performance. Its implications, however, are profound. The absurd malleability of borders is clearly revealed to those that engage with it. The work for Bunting marks an ironic reversal in which his desire to escape the UK is achieved through travelling back into it.

The density of Bunting’s work is deftly offset with the installation of Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries, Notes on the Downtown Eastside (from the East Vancouver Trilogy), (2011). In this work, a text is presented as a flash animation file, accompanied by a woozy jazz soundtrack. The text outlines the collisions with urban space the collaborative duo experienced in Vancouver, how art is present everywhere in everything – from a bus journey, or a conversation about a coat, to the demarcation of a city street for a police investigation. In Notes on the downtown Eastside Young-Hae Chang declare that they work conceptually with “unfiltered culture” which is for them not unlike "unfiltered cigarettes" just less "carcinogenic". They directly engage with the sides of urban place that the city fathers don’t want you to see, the spaces that hold a baffling logic that engages creativity. Inequality, poverty, public transport are present as is the potential for bonds to be formed through passing conversations.

This Downtown Eastside shares commonalities with many others, including the rapidly transforming environment that Vivid is presently sited in. An articulation of the capital that unravels and transforms the spaces we occupy can be found in two animated gifs by Lorna Mills that depict body-slamming grim reapers and a waterfall of baby chicks. Money 2 is a cacophonous revision of Pink Floyd’s song ‘Money’. The work articulates the evolutions of late capitalism that have taken place in the forty years since the song’s recording and charts our desire for endless transformation in the spaces we occupy. Mills questions the validity of Pink Floyd’s calls to reject wealth in the face of our present economic instability, seeing instead the absurd desperation caused by money’s presence or absence as a constant contemporary anxiety.

An installation of Rafaël Rozendaal’s website Infinite_Thing.com closes the exhibition, a snail trail of moving graduated colour. The work jumps and reformats itself when you interact with it through a click on its web-page. In the gallery, the work is left to play out in its own time and space, a neon Möbius strip that exists beyond need of our engagement.

The slippages between physical and digital space that DOT.ART engages are expansive. As a viewer you are given offline and online space and encouraged to work through your own implications within both of them. The show encourages you to be curious, to search further than the works it articulates itself with, to open tab after tab on your browser, and look more intently at the world we function within.

DOT.ART is at Vivid Projects, Birmingham, from 6 May – 27 May 2017