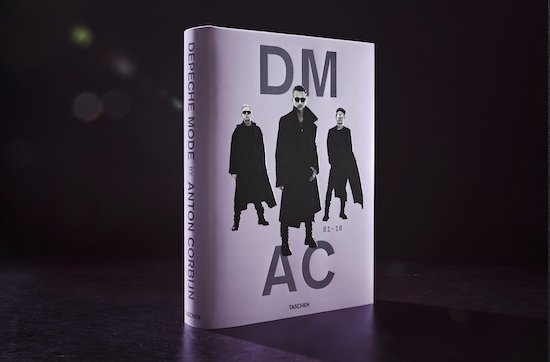

Talking about Depeche Mode by Anton Corbijn, the duly and understandably massive photo collection showcasing the latter’s photographic and design work for the band over nearly four decades, is a bit difficult to do with any sense of remove if you’re a fan. And believe me, I am – both of the band, one of my lodestone acts for almost as long a time, and of the artist, whose aesthetic sense has lent itself to more moments musically and movie-related which have sunk in with me than I can easily count or take stock of. I can’t claim Taschen designed this book just for me, but in a weird and real sense, that’s how it feels. Depeche in particular always seem like one’s own unique secret, even now.

Which is patently ridiculous any number of times over at this point. That was clear enough even before they released their world-beating Violator, as the still remarkable 101 concert film makes clear (I’ve sung its praises in this publication, after all). But Corbijn, in both his running (and, appropriately, hand-written) commentary throughout the collection and in the introductory interview, hits on something that remains notable about Depeche – that they seem always a bit out of sync with the celebrity culture that they’ve dwelt in by simple default for so long. They’re not a faceless band by any means but more than once I often felt like the UK band they most resembled, despite there being absolutely no musical connection unless you squint a lot here and there, was Pink Floyd. In both cases, a collective with recognizable elements, a subcultural impact that was the result of outsider obsession, an irregular chart presence that it always felt like someone, somewhere, was forced to accept in the face of overwhelming evidence.

Corbijn himself feels like someone who can also be in that role all by himself, like he wasn’t going to ask for permission to do exactly what he wanted to. It may be the myth of artistic genius at work (and it’s a great myth, don’t get me wrong) but Corbijn deftly acknowledges the context for all the work throughout – photo shoots for magazines, press shots for public relations kits, outtakes from video shoots, concert shots showcasing the band on stages Corbijn himself designed. In ways, the sense of filthy lucre at play is precisely the point; much in the same way 101 merrily dove into the nuts and bolts of large concert staging and money-man arguing in trailers, you never totally escape the sense of presentation, marketing and more. But that makes it all the more appealing, and it’s also pretty Corbijn as well – show the joins, don’t worry about a perfect backdrop or setting each and every time.

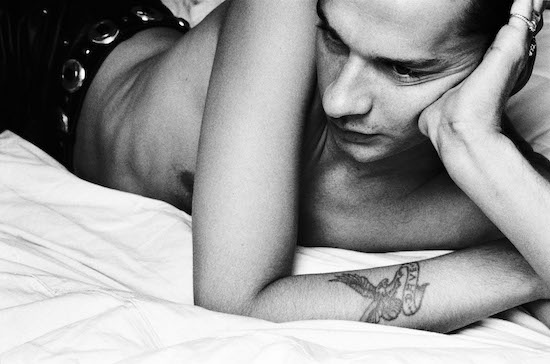

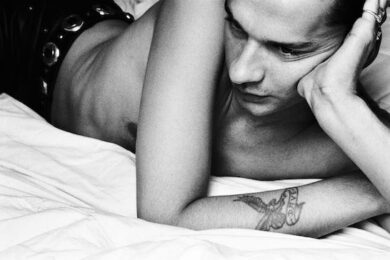

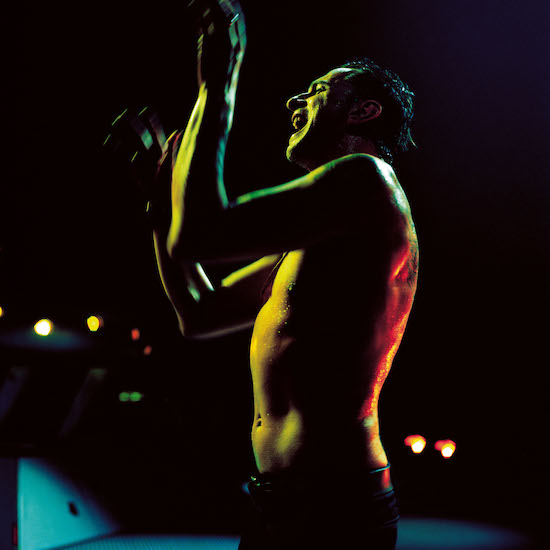

It’s easy to summarise or even parodically describe what a ‘typical’ Corbijn photo is – grainy, black and white, set somewhere slightly crumbling or scuffed and with at least one person in a shoot potentially out of focus – which speaks in large part to the power of his earliest visual brand, when his New Musical Express work, from his still image-defining Joy Division shots forward, provided a stark counterbalance to Smash Hits dayglo brightness in print. The book shows how his gift for that approach absolutely remains from start to stop, but it’s not just that by any means. As time goes on, you sense – and Corbijn points out some details as goes – when he changes up film (not just the introduction of colour shots, but changes in grain and more), experiments with focus and staging, varies the posed with the casual. It all feels like a work in progress, the world’s longest photo shoot.

That, in turn, is the real key to this collection – its uniform focus, the story of a band. There’s plenty of little surprises throughout, starting with quite literally the first shots, an early Depeche gig opening for Fad Gadget in 1981, Corbijn there to photograph the headliner and just taking a couple of shots of the opener for the heck of it. But even one of those is weirdly iconic – Dave Gahan, Martin Gore and Andy Fletcher, with Vince Clarke hidden behind Gahan, and from there it’ll be almost forty years of seeing them grow up, age, become young men, then middle-aged, then more. Alan Wilder of course features as well in the run of photographs from 1986 to 1994, and rightly so given his key role in developing their sound and aiming it for the skies, but in the end it’s seeing those three grow, change, take on new personae by default. The period of Gahan’s absolute drug hell is all too clearly evident; when Corbijn notes photoshoots where Fletcher was mostly away dealing with a depressive bout, it makes the few examples from said shoots with him in them suddenly poignant. Similarly as they’re captured in better days, you sense the lightness return, the grizzled veteran status feeling well earned.

Yet at the same time there’s variety, there’s also a constant throughline with endless variations, sometimes deeply serious but often very wry, always with a sense that Corbijn has captured them just so. Divorced from the sounds of the band, the context they were found in and categorised as, Corbijn’s subjects seem like the ultimate family gathering snapshots mixed with efforts at joint work get-togethers, with haircuts or facial hair that might immediately mark an era as much as anything else. They’re as apt to point and laugh at something apparently off camera or in response to something someone’s said as to give the lens a direct stare, slight smiles or brooding frowns varied with twinkles in the eye. There’s one lovely two-page spread with various shots in the early 90s featuring each band member with one of their young children, a great unexpected ‘bring your kid to work’ moment that many others – perhaps especially after these last two years – can imagine easily.

Meantime, Corbijn’s eye for settings is often breathtaking, even beyond the live stages and video setups he created directly. Sure, there’s indeed plenty of crumbling structures and peeling paint – with photoshoots literally all over the world, Corbijn seems to always know where to find spots where gentrification hasn’t happened – but there’s towering trees, sweeping desert scrub, oceans to the horizon, drowned swamp forests, all of which help to situate the sense of Depeche-as-band as something even stronger, a near natural force. When he does shoot in colour the contrasts he finds or designs can be intensely vivid, deep blood reds, intense blues. Even towards the end of the book, when the various sessions tend to be readily grouped into ‘album session shots/EPK poses/making-of video moments/live shots’ that all occur once every four years, there’s always a little something that’s random and striking that turns up, along with extra details, like the fact that the shot also featured on the book’s cover of the band in long dark coats, seemingly a winter shoot, was shot outside on a blisteringly hot New York summer day.

Given Corbijn’s massive stature in his field combined with fan-thrall for everything Depeche, it’s little wonder the initial limited edition of the book released last fall sold out almost immediately; this version’s bigger print run will help on that demand front – the expense needed is clear enough but Taschen knows what they’re doing in their own field in turn as a publisher. Hard enough for me as it is to talk objectively as noted, it is, simply, well worth it, a documentation of a collaboration that covers the iconic and the everyday in a way that just endlessly works, time and again. Reach out, turn a page.

Depeche Mode by Anton Corbijn is published by Taschen