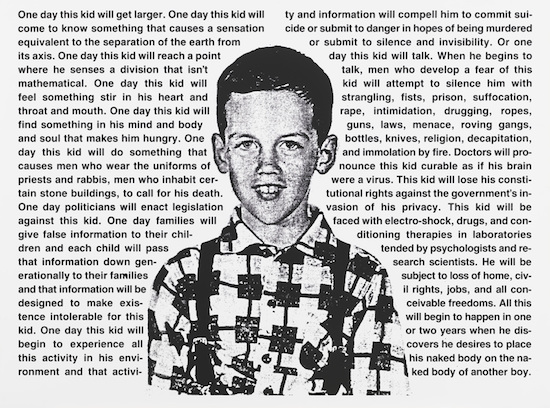

David Wojnarowicz(1954-1992), Untitled (One day this kid . . .), 1990-91. Photostat mounted on board. Sheet: 29 13/16 × 40 1/8 × 3/16in. (75.7 × 101.9 × 0.5 cm). Image: 28 1/8 × 37 1/2in. (71.4 × 95.3 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Print Committee 2002.183. Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Some consider the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2018 retrospective of David Wojnarowicz to be overdue. But considering our current societal and political climate and the atypical, acerbic, and angry work the radical artist created, perhaps History Keeps Me Awake At Night arrived right on time.

As a practitioner, Wojnarowicz made use of whatever he could get his hands on and never married himself to a single medium. Scratchy black and white photography; messy multimedia stencilling; found objects such as trashcan lids from the streets of New York; the dissonant musical subgenre of No Wave; the immediacy of language and the written word – everything had potential. Wojnarowicz wasn’t a jack-of-all-trades so much as he was a punk polymath. And the Whitney acknowledged the non-linear messiness of Wojnarowicz’s art and life by showing a wide breadth of his work.

The exhibition began, not unexpectedly, with Wojnarowicz’s early Arthur Rimbaud In New York photo series: an audaciously queer collection of his New Yorker friends wearing Rimbaud masks and sitting on the subway, smoking in cafés, or shooting up in alleyways. The black and white photos, shot from Coney Island to the Meatpacking District – and all on a borrowed camera – revelled in nonconformity and otherness, while simultaneously fleshing out the coexisting pains and pleasures of being human. Not only did the series lay the foundation for viewers who weren’t familiar with the artist, but it also set the tone for Wojnarowicz’s own art career. (It does feel like a disservice, however, to attribute the hollow word “career” to Wojnarowicz – because it wasn’t a career, really. It was his life. And it was nothing short of a rebellion.)

The room leading on from Arthur Rimbaud In New York was typically Wojnarowiczian – it combined multimedia stencil work with overhead music from No Motive, the only album released by his lo-fi No Wave band 3 Teens Kill 4. The found-sound, jittery guitars, and rheumatic thump of electronic snares lent itself to the scattered visual bombardment of his stencilling, which combined imagery of cross-hairs, war planes, burning buildings, and kissing men – all in a rainbow hue of colours. As gallery goers manoeuvred around these earlier works, which ruminated on political crises, human vulnerability and human-rights issues – while also having the lyrics “This is a robbery!”, from 1983’s album-opener ‘Hold Up’, shouted from the speakers – the relevancy of Wojnarowicz in the modern day made itself apparent, even two and a half decades since his death in 1992.

David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992), Untitled (Green Head), 1982. Acrylic on composition board, 48 × 96 in. (121.9 × 243.8 cm). Collection of Hal Bromm and Doneley Meris. Image courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

From the get-go, a politically astuteness and hyperconsciousness of the structures which society operates under was a trademark of Wojnarowicz’s work. But it was when the AIDS crisis began to ravage the gay populace of the United States and, particularly, New York City, that Wojnarowicz’s already rapid output of work increased to an intense degree. As Wojnarowicz became aware of his own fate, he created a barrage of photos, personal writings, and visual works. He made the art in an attempt to make sense of the nonsensical: the epidemic which resulted in the untimely deaths of lovers, friends, and, subsequently, himself.

In acknowledgement of the urgency with which Wojnarowicz worked in the last few years of his life, the Whitney dedicated the second half of the retrospective to these later pieces. One space, in particular, was devoted solely to aural recordings. Through muffled audiotapes, Wojnarowicz’s unrelenting voice was heard overhead as he read excerpts from a 1992 short piece titled Spiral, the 1992 book Memories That Smell Like Gasoline, and his 1991 book, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, in which he examined the politics of marginalised identities, the invisibility and the taboo nature of infection and illness. By the sheer insistence of his tone, Wojnarowicz wrestled the listener into acknowledging the troubled nature of his times.

One particular excerpt from Close to the Knives, unfortunately, didn’t sound too dissimilar from our present: “‘If you want to stop the AIDS, shoot the queers’ says the governor of Texas on the radio, and his press secretary later claims that the governor was only joking, didn’t know the microphone was turned on. Besides, they didn’t think it’d hurt his chance for re-elections anyways.”

Those who are at the helm of power now, in 2018, can say inexcusable things and carry out atrocious acts still, all while not damaging their electability – or re-electability – in any major way. As 3 Teens Kill 4 put it in 1983, “This is a robbery!”

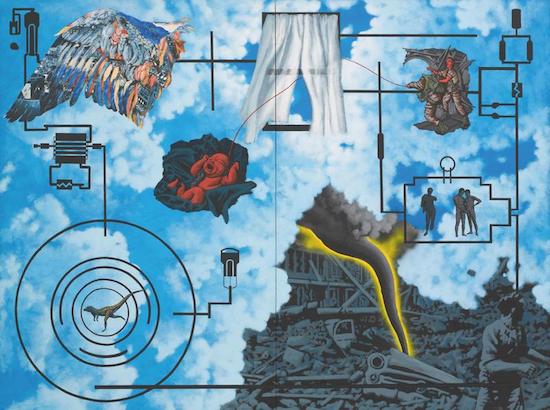

David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992), Wind (For Peter Hujar), 1987. Acrylic and collaged paper on composition board, two panels, 72 × 96 in. (182.9 × 243.8 cm). Collection of the Second Ward Foundation. Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

Beyond the audio space, the concluding rooms of the exhibition re-focused on the artist’s visual work. Wojnarowicz enthusiasts will immediately notice the Peter Hujar triptych: a haunting photo series which documented the last moments of Wojnarowicz’s former lover, as he finally succumbed to AIDS-related pneumonia at the Cabrini Medical Center in New York. The first panel had Hujar’s head slumped on a pillow, his eyes barely open (and, without proper attention, it may have seemed his eyes were closed shut). In the second panel, Hujar’s bony hand rested lightly upon a white hospital bedsheet. And in the third, his feet – with the right foot upright and arched dramatically, while the left foot angled sideways in a despondent way – protruded from under a duvet blanket.

History, indeed, keeps us awake at night – as does our present. The current showcasing of Wojnarowicz’s work, however, isn’t about an artist whose work has been isolated in time, so much as it’s about an artist whose voice, artwork, and thinking have transcended time. Wojnarowicz once wrote: “WHEN I WAS TOLD THAT I’D CONTRACTED THIS VIRUS IT DIDN’T TAKE ME LONG TO REALIZE THAT I’D CONTRACTED A DISEASED SOCIETY AS WELL.” And although some circumstances have certainly changed, we must consider whether our “diseased society” has been remedied at all since Wojnarowicz’s death.

David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night is at the Whitney Museum of American Art until 30 September 2018