This is an outwardly austere show that modestly hints at the great ambition of the artist. Time is Darren Almond’s big theme putting him in some very exalted company. The question of time preoccupied Marcel Proust too of course and he in turn attended Henri Bergson’s classes on the subject as it related to philosophy. Bergson, we learn in Józef Czapski’s extraordinary lectures on Proust given in a Soviet prison camp, “insisted that life is continuous and our perception of it discontinuous.” This key paradox is germane to an understanding of Almond’s work.

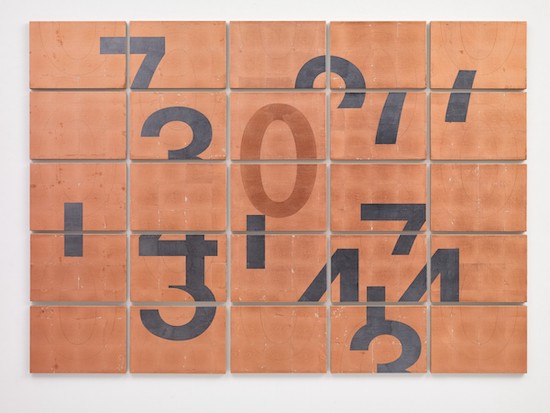

The paintings here, some rendered with concrete-based mineral paint, feature numbers on several grids of rectangular panels but the digits are sliced and spliced, they are in bits. So for example we might see the top triangle of a figure ‘4’ separate from its stem, the top curve from a ‘2’ displaced from its base. They look like cut-up Sudoku puzzles. The font used for the numbers reminds me of station clocks. These markings then can be seen as little ticks of time. Zeroes are prominent, sometimes centrally placed, and are deliberately kept intact to stress the importance of the number. I look at the sequences quizzically and try to make sense of the data but the discontinuities stump me – just as Bergson noted.

Almond provides clues in the materials he uses for these paintings and the titles he supplies. A knowledge of his past works helps. Timepieces, such as A Bigger Clock (1997) shown at the Sensation show at the Royal Academy, have long featured in his practice. His videos (not shown here) often report his travels to far-off places: he’s something of a Bruce Chatwin figure, a Romantic attracted to the exoticism of the remote, the thrill of the Sublime. Many of these films feature the workings of mines or other environmentally unfriendly activities. He’s not didactic about this – these works are not party political broadcasts on behalf of the Green Party.

The grid paintings are often made with layered metal leaf using elements such as copper, silver, gold, aluminium or palladium. Some of the paintings are named after famous mines such as Escondida (all works 2018), the famous Mother Lode of copper found in the Atacama desert of Chile. Others hint at Almond’s earlier trips to the far North and are named after ships, icebreakers, as with Yamal and Arktika. Almond sailed on these behemoths through Northern Russia as part of another project. He was interested in the mining regions of this area made infamous by the atrocities of the Gulag. Palladium and nickel are still mined at the Norilsk complex above the Arctic Circle in Russia, the site of one of the most notorious prison camps. And so Almond points here to both the planet being relentlessly gouged for our insatiable greed and the grotesque history of slave labour.

Elsewhere Ugetsu shares its title with the 1953 Japanese movie by Kenji Mizoguchi and references Almond’s extensive and well-known Full Moon series of photographs (also not on display) taken following a period of lengthy exposure to light from the moon. ‘Ugetsu’ means something like ‘invisible moon’; a moon obscured by rainclouds, and directs us to Almond’s civil dawn landscape photographs that reveal a rarely seen world of placid, limpid, beauty.

There is another sequence of mineral paint and pencil works called A-la-mi-re I –IV that may refer to Pierre Alamire, best known as a sixteenth century German-Dutch composer and music manuscript copier. In addition he was a diplomat, a spy and also, crucially given the themes here, a mining engineer. His main claim to fame in turn tunes us into the sound component of the show.

Intermittently the silence of the gallery is broken by At Sea, a four minute thirty-three second recording obtained from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich of 18th century marine timekeepers built by John Harrison (c.1693-1776). The chimes sound like a gamelan and are charmingly colourful. These contrast strikingly with the restrained tones of the imagery on the walls. What we hear is surprisingly modernist sounding too, as if it were a piece by John Cage. The silence then returns, another time zero if you like, another nothing, and is of the same duration – a nod of course to Cage’s most infamous composition.

Yet another work, Eppur si mouve, points to a saying accredited to Galileo: ‘And yet it moves’. The great genius is reputed to have said this after being forced to recant his claim that the earth moves around the sun – as if to say ‘it doesn’t matter what you or I say – these are the facts’. For Almond time and numbers are the facts, there’s no getting away from them. In eras like Galileo’s or ours, times of gross duplicity, numbers still tell the truth. And the concept of zero is important for Almond. Without it we can’t get anywhere; we can’t count, we don’t count.

Lastly in a white room on its own is one of Almond’s signature trainplates mounted on the blank wall – an aluminium plaque similar to those that have graced and named British inter-city trains for many years. This is another hint to his viatic lifestyle and the lettering announces the title of the show: Time Will Tell. A cliché perhaps but we know that it will, that it always does.

There’s much talk of the Anthropocene these days, our age of geological time dominated by humanity and its destructive effects on planet Earth. Almond’s art addresses this, his fractured numbers align with our systems collapsing, he’s whispering to us that our time’s up. We’ve blown it. But those little ticks of time know no reason, know no rhyme, and are indifferent to the fact that we will all come to naught.

Darren Almond, Time Will Tell, is at White Cube, Bermondsey, until 20 January