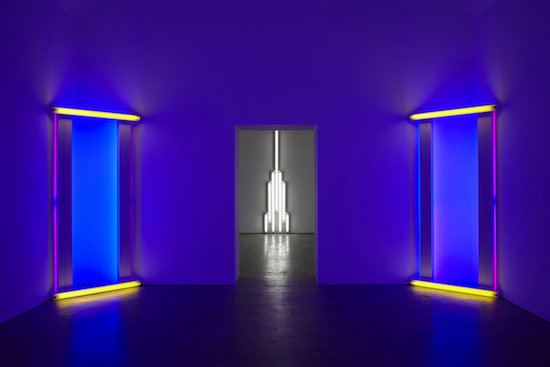

Dan Flavin, It is what it is and it ain’t nothing else. Installation view, Ikon Gallery (2016). Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy of Ikon. © 2016 Stephen FlavinArtists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Dan Flavin’s ‘propositions’ are not best seen one at a time. I first saw one (I think it was one of the 60-odd versions of Monument for V. Tatlin) at the whistle-stop tour of art’s greatest hits that is the Tate Modern, but on its own it was frustratingly difficult to engage with. Denied a dedicated temple like the Rothkos, the light from his fluorescents wasn’t given the space to spill out luxuriously across a whole room. The harsh white glow interrupted – and was interrupted by – other works in the same space in more traditional mediums. And of course, in London, there are always too many people.

No such problem in Britain’s second city – one pm on a Sunday and the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham’s glitzy canalside quarter is almost empty, despite offering free entry. The exhibition, It is what it is and it ain’t nothing else features sixteen of Flavin’s works made solely from different configurations of fluorescent light tubes, positioned around seven small spaces in an unusual building where the galleries are small and stacked vertically, the minuscule Tower Room at the top.

After reprimanding me for taking a photo (why?), an enthusiastic attendant talked about the difficulties they’d had in curating Flavin at a relatively unconventional gallery. Fake walls needed to be built, windows blacked out and blocked up, and spaces reconfigured to eradicate the light that usually floods the converted Victorian schoolhouse through its arched windows. Presumably this wasn’t as much of a headache when a similar Flavin retrospective was held in 2006 at London’s Hayward, a bunker-like space seemingly built for a millionaire with a sun allergy.

It’s ironic that a show of his work is such a pain in the arse to put together, given the levity and simplicity of his basic materials. untitled (to Dorothy and Roy Lichtenstein on not seeing anyone in the room) even demands the construction of an empty room, inaccessible to the audience but visible through a series of narrow slits in the wall, the lights illuminating the room but invisible to the viewer. It’s a good joke that played into my obsession with not missing anything in an exhibition (I found myself examining the guide map before I realised). You know the piece is there but you can’t see its constituent elements, only the effect it has on its environment.

What is so innovative about Flavin that makes putting him on worth all this bother though, given that your average Dubai hotel sports a neon spectacular ten times the size? Now his style is aped in every Cineworld and Singaporian shopping mall, it’s easy to forget what is so revolutionary about the work that he devoted himself to from the early 60s until his death in 1996.

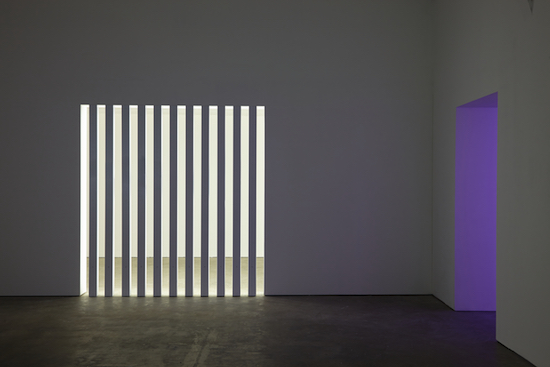

Dan Flavin, It is what it is and it ain’t nothing else. Installation view, Ikon Gallery (2016). Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy of Ikon. © 2016 Stephen FlavinArtists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Reflecting an obsession of 19th century art, painters such as Turner and Klimt devoted their entire careers to creating the illusion of light shining out of their canvases. Starting in 1963 when he made his first sculpture from a diagonal yellow fluorescent, Flavin took this aim to its logical conclusion and cut out the middle man, simply presenting light to the viewer without the pretext of a landscape (Turner) or a shimmering golden dress (Klimt). The American chocolate-box painter Thomas Kinkade ripped off Turner by stylising himself as the Painter of Light™, but Flavin painted with the light, the host gallery and its unique space forming an ever-changing canvas with each new exhibition. Far more than with painting or traditional sculpture, the work is radically reinvented each time it’s installed in a new space: the size and shape of the gallery, even the shade of white on the walls, become factors as important to the final effect as any input of the artist.

Flavin’s pieces are pure feeling – it literally radiates from his work without the need for a conduit or metaphor. The emotion he conveys through his lights arguably feels more immediate than that of traditional sculpture as each piece is constantly being created in real-time, a kind of permanent performance art. If unplugged, it instantly ceases to exist. Stand close enough and you can hear a faint hum.

Flavin allows you – almost invites you through his sheer universality – to project your own emotion onto his lights. They can represent the intense throb of pain that comes with an unrequited crush, the breakup of a relationship or even grief, or they could be pure love. The show’s title is a quote of the artist in which he rejects any spiritual or transcendental reading of his art, suggesting that he would prefer it to be viewed and experienced in a more direct, humanistic sense – as expressions of our everyday feelings and desires. His work uses no written language and makes no overt references, except in the titles which sometimes feature a dedication, hinting at but not confirming a meaning. Only occasionally, such as with his red Vietnam protest Monument 4 for those who have been killed in ambush, does he make the motive behind his chosen colour overt – anger in this case.

Dan Flavin, It is what it is and it ain’t nothing else. Installation view, Ikon Gallery (2016). Photo by Stuart Whipps, courtesy of Ikon. © 2016 Stephen FlavinArtists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Speaking of intense emotion, something that isn’t pointed out in the gallery guide is how strongly Flavin’s work seems to foreshadow the rave aesthetic. Forward-thinking clubs that are known for minimal yet imaginative lighting design – say, Frankfurt’s Robert Johnson or Amsterdam’s Trouw – have taken cues from his work, suspending different coloured tubes above their dancefloors to stark but striking effect. Look at the sleeve of South London Ordnance’s latest EP – there’s a single white fluorescent, held in the air between two stacked chairs in a gallery-like space. Flavin’s white lights, such as the four Tatlin pieces at the Ikon, are clinical and clear-headed. His colour pieces, particularly those which cause blues, greens and purples to bleed into each other on the wall such as the kaleidoscopic untitled (in honor of Harold Joachim) 3 at the Ikon, are seductive, a little messy – even hallucinogenic.

His work isn’t seen as often as it should be. Maybe that’s because of the logistical challenges of presenting it or because his work is best seen all at once, or perhaps there’s an unknown commercial reason. It’s unfortunate, because in an era where even mainstream pop music is now expected to arrive loaded with hidden meaning and overweight with cultural cross-reference, Flavin’s warm take on minimalism is more vital than at the time of his death. His rejection of attempts to over-intellectualise his work is liberating – he simply took the technological detritus of consumerism and reprogrammed it to reflect the values of real people, rather than the architects of office blocks, airports and Las Vegas casinos.

Dan Flavin, it is what it is and it ain’t nothing else, is at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, until 26 June