Crumb’s World, 2021. Photo by Alex Casto. Courtesy of David Zwirner Books

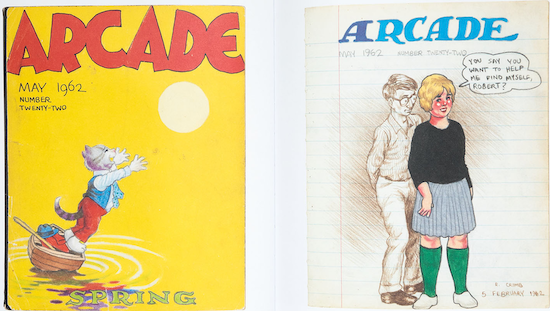

In 2016 Fantagraphics, who have republished much of Crumb’s work, released a book about its own history titled We Told You So: Comics as Art, and the appearance of Crumb’s work in the context of the art book market (Crumb’s World is from New York’s David Zwirner Gallery) is the logical conclusion of the campaign to make people take comics seriously. Another logical conclusion to the “comics as art” campaign is the price: Crumb’s World retails for £35. It historicises Crumb in a cartooning and satirical tradition that dates back to Hogarth and reproduces pages and covers from throughout his career.

The thing to remember about comics is that it started as a pulp medium and it’s typically always developed best in low budget formats. Even Art Spiegelman’s acclaimed holocaust narrative Maus started out being serialised in comics anthology RAW. Crumb started out drawing in notebooks under the tutelage of his brother, and was already an impressive draughtsman at the age of nineteen. By the late 70s he’d fully formed his trademark style – elongated figures immersed in urban infrastructure that appears as blocks of colour – and made his mark self publishing Zap Comix.

Post Fredric Wertham’s 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent and the subsequent rise of the Comics Code Authority, mainstream superhero comics became the all-American propaganda they continue to be today. The self-published comix scene was the reaction to that rise of mediocrity and self-censorship. The counterculture wanted comics about drugs and paranoia. It also saw itself as inherently progressive, but this is one claim Crumb could never indulge. Crumb has argued that Angelfood McSpade, perhaps his most violently racist caricature, is an attempt to appropriate America’s imaginary subconscious and tell liberals that this is part of their culture, too, no matter how much flower power they think they’ve got. He had, as he said in 1994, “the desire to mush America’s politically correct hypocrisy in her face.”

Crumb’s mission to deconstruct racism by pointing out how pervasive it is would have perhaps been more successful had it taken place within a context where that deconstruction was explicit. (I think of the mindful Chris Ware, who in Monograph describes how when drawing Mickey Mouse without the ears all one’s left with is a racist caricature.) Crumb might be clever with exploiting visual tropes but his stories are often as repugnant as the stereotypes, and when the plot is as ignorant as the characters, his comics can feel like a doubling down on what is already a very uncomfortable ride. In terms of narrative, Crumb’s World highlights the artist’s interest in the postmodern breaking of the fourth wall, and discussing the art of narration within the story.

His portrayal of women is as complicated. For starters, he’s never claimed to be deconstructing sexist stereotypes. Crumb’s very honest about his inhibited lust; his buxom and muscular female trope has often been deployed as the counterpoint to the scrawny and sexually divergent male. In his comics, women are often objects, literally so, for his male characters to drool over – and worse. In more recent years, such as in the Art & Beauty series, Crumb has transitioned to cross hatched photo realism, and in Crumb’s World you find a reproduction of his strikingly powerful portrait of the much maligned Stormy Daniels.

It’s not all problematic, of course. His cover designs are eye-catching and adventurous, often playing with the EC Comics style that Crumb no doubt devoured as a kid. One of the most enlightening parts of Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb documentary film is when the artist discusses taking photos of skylines and roads so he can accurately recreate the ambience of all the wires and poles that become visual background noise in the everyday lives of city dwellers. His representation of “the city” in the abstract is instantly recognisable and very effective. I also interpret the message of a rejected cover for The New Yorker, included in Crumb’s World, as highlighting the right wing’s and the state’s ridiculous and reactionary discomfort with gender nonconformists.

Robert Storr, the critic and curator who writes the introduction in Crumb’s World, compares Crumb to the likes of John Waters and Quentin Tarantino. He also draws attention to the influence of Art Young upon the artist. Young was one of the preeminent anti-capitalist cartoonists in the US in the early 20th century, and like him, Crumb has a distaste for greed and commodity culture. Also like Young, he is concerned with the effects of this culture upon the individual. His visual flair has also filtered into what can uncontroversially be described as good work. Joe Sacco’s toothy avatar, not a far cry from some of Crumb’s cartoon self-portraits, has walked us through some essential comics journalism.

The most frustrating thing with Crumb is all the umming and ahhing you have to do around his work. Maybe I’m one of those libs he always wanted to frustrate, but I also think he failed on his own terms when it came to critiquing drawing’s role in the American unconscious, and my feeling is that this is because of his postmodernist tendencies. When it’s hard to spot what’s serious it’s difficult to tell what the joke is – or who the punchline lands on.

Storr’s conclusion differs. His introduction makes a defensive case for Crumb, powerfully arguing that, “You may not care for a musical virtuoso’s repertoire, but it is all but impossible to ignore his performance.” His text resembles many of the anti-cancel culture arguments that are scattered around the internet at present. While it’s easy to envision how, had he arrived a few decades later, Crumb would have for sure gotten mixed up in the culture wars, it’s hard to guess which sides of the debate would have said what about him.

As Amy Marie Pederson writes in her thesis about Crumb and the American comix movement: “the negotiations of the Surrealists in their struggle for psychological emancipation from the repressive nature of the culture they inhabited crumpled before the horrific intrusions of Nazism and Fascism in Europe, as did Zap’s exercises in mental liberation fade and wither when faced with the overwhelming pessimism engendered by the failure of the naively optimistic intentions of the 1960s to translate to the following decade.”

It’s here we arrive at the limits of Crumb’s work, the borders which close it off to being transformed or reappraised by future generations. Being so entwined with the libertarian ideology it came about in means Crumb’s most famous work becomes mere historical evidence; archival documents with embarrassing and sometimes odious features. Many of the cartoonists that have appropriated his style have taken comics to where the medium needed to go: political, concerned with ethics, playful rather than aggressive. The world that gave birth to Crumb is gone; Crumb’s World is proof of that.

Crumb’s World by Robert Storr is published by David Zwirner