“I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed.” The message comes from the artist Linder Sterling, via Christopher Isherwood, from the pages of whose Farewell to Berlin the lines are quoted. Isherwood himself would come to regret these “infamous” lines, after John van Druten’s play took their first four words for a title and made them the most recognisable in Isherwood’s entire oeuvre.

As Armistead Maupin would write in an introduction to the New Directions edition of Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, the latter was far from the “detached and clinical” observer suggested by the camera metaphor. But today, it is less the opening gambit than the final sentence that catches my attention and stays with me as I make my slow trek home again, back through Shoreditch and across the river. “Some day, all this will have to be developed.” But not now, the words suggest, not yet. Too soon.

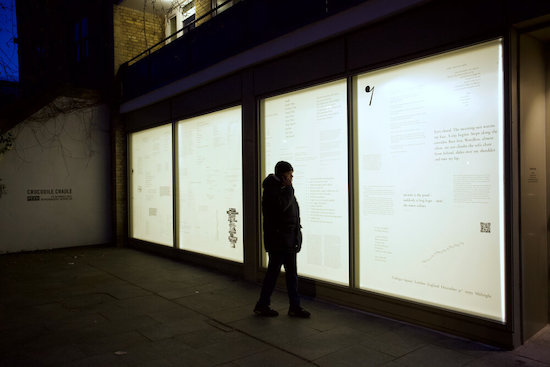

I’m standing on the pavement in Hoxton, opposite an FE college, out.side an art gallery whose doors have been closed to the public for months. A long queue for the post office next door curves around me, snaking its way down the street. It is a bright, unseasonably warm February day in the midst of London’s third Covid lockdown. I’ve come here for two reasons. On the one hand, there’s a shop just round the corner which is a very reliable source of the rendang flavoured instant noodles I have recently developed an addiction to. On the other, Peer Gallery has covered up its four big front windows with off-white sheets bearing short texts from a variety of contemporary artists, part of what the gallery’s website calls, an “exhibition on three platforms: a filmed performance online, accessible via a QR code; a text collage on the gallery’s glass façade; and a book, to be published this summer.” The artists in question include Christian Marclay, Fiona Banner, Pavel Büchler, Lubaima Himid, Cerith Wyn Evans, Tacita Dean, Sophie Jung, Liam Gillick, John Armleder, David Horvitz, John Smith, Andrea Bowers, Stefan Brüggemann, Erica Baum, Helen Cammock, Cally Spooner, Sylvie Fleury, Ugo Rondinone, Peter Liversidge, Jonathan Monk, and Linder, along with the show’s curator, Simon Moretti.

There is little to connect the various missives, aside from the yellowed plane they cohabit. Each was asked simply to “supply a text that they have written or found.” Hence several artists – like Linder, but also Jiří Kovanda (who chose a Bashō haiku), Marcel van Eeden (who excerpts from a short story by Alan Wykes), and Cally Spooner (who cites an interview with the philosopher Manuel DeLanda) – have contributed short quotes in place of any words of their own. Israeli artist Amikam Toren quotes a letter from Samuel Taylor Coleridge to his friend Thomas Poole, “If I do not greatly delude myself, I have not only completely extricated the notions of Time and Space.” Coleridge’s letter signalled the increasingly opium-addled poet’s break with the philosophy of the eighteenth-century Christian necessitarian David Hartley and turn towards a more speculative – even hermetic – sort of metaphysics. But in the context of the current pandemic, the notion of overthrowing time and space sounds strangely quotidian. Like, sure, who hasn’t?

A little less than a year ago, during lockdown #1, I had an idea that I was going to start sending postcards to my friends. We couldn’t see each other and I pretty much hate talking on the phone or via Zoom or whatever so it seemed like a logical thing to do – and perhaps a way of leaving some small tangible trace behind of this peculiar moment in history. I started gathering people’s addresses, scouring the flat for postcards I might have bought at some point or another and never filled or sent, even bought one or two new ones from one of those little touristy shops near London Bridge, and then somehow never quite got round to it. But standing out here on Hoxton Street, reading all these short texts from artists all over the world, feels a little bit like receiving a bumper crop of postcards in the mail. There is a tentativeness to these words (recall that “Some day…” of Isherwood’s quoted by Linder), a sense of being dashed off quickly in an odd moment, as well as a brevity and immediacy, that seems to call towards that medium.

Many artists have used postcards as a sort of readymade canvas, its diminutive frame a contemporary equivalent to the Persian miniatures of the Safavid era. In 2019, the British Museum devoted a whole floor to artists’ postcards, from doodles by David Shrigley to Eleanor Antin’s photo series, texts works by Simon Cutts or John and Yoko, conceptual fillips by Ben Vautier, like The Postman’s Choice, a blank postcard with a stamp and a different address on each face. But few have been more intimately associated with the form than Ray Johnson, founder of the New York Correspondence School. In the 1960s and 70s, Johnson posted collages, drawings, and texts to friends, collaborators, other artists, and members of his ‘school’, often with an invitation to “add to & return”. As a practice, it “interrogates and disrupts the notion of authorship and the inevitable commodification and institutionalization of art,” as Tim Keane wrote in a 2015 piece on Johnson for Hyperallergic. “The work is simultaneously cerebral and visceral, markedly private while fostering community.” Much the same could be said of the messages on Peer’s window.

There are works here that fit right into what we know of the usual output of the credited artists: the freeform wordplay of Sue Tompkins and Sophie Jung, for instance, or Christian Marclay’s jagged ziggurat of “aaargh”s and “Nyaaaaa”s and “Grrrrr”s snipped from various comics. Cesare Pietroiusti’s almost Fluxus-like set of instructions (“Collect everythign which is visible in a given environment and take it elsewhere.”) recall the Italian artist’s Non-Functional Thoughts (1978–2015). Others are more surprising, harder to place: a surreal, Mallarmé-like poem by Cerith Wyn-Evans, full of blank space and words under erasure. Jonathan Monk seems to be inviting us to a rendezvous that most of us will not be able to make: “Trafalgar Square London England December 31st 2999 Midnight”. But the contributions I find myself most drawn to are the slightest, the most meagre: Sylvie Fleury’s exultant “YES TO ALL”, for instance. John Armleder’s response is just one lone musical symbol – albeit one that feels distinctly apposite right now – the sign for a quaver rest, that is, a very brief pause.

I’ve often wondered over the last twelve months, with all the galleries and museums shut, why aren’t more artists doing stuff outdoors, in public, for anyone to see. Projects like The Line that runs down the meridian from Stratford to Greenwich are sort of perfect for an epoch necessitating widespread social distancing and ventilation. But I’ve seen less of that than one might have expected. Part of the reason, no doubt, is simply a question of the time it would take to get another project like that of the ground. But I wonder if part of it is due to the almost inbuilt expectation that a big outdoor art work appearing at this time should somehow ‘respond’ to the historical moment in some way and I suspect a lot of artists are simply not very keen to do that, at least not yet. A project like Moretti’s here at Peer offers an alternative possibility: a chance not to ‘respond’ so much as to simply react or register, to throw out a few words that have buzzing about your head, a quick sketch, a quote that caught your eye, like a message in a bottle, or a postcard. Like Isherwood in Berlin, these little texts record something of the moment in a less grandiose, less final way. “Some day, all this will have to be developed.”

Crocodile Cradle is at Peer Gallery, London, until 20 march 2021