“A small child is taken to the zoo for the first time. This child may be any one of us or, to put it another way, we have been this child and have forgotten about it. In these grounds – these terrible grounds – the child sees living animals he has never before glimpsed; he sees jaguars, vultures, bison, and – what is still stranger – giraffes. He sees for the first time the bewildering variety of the animal kingdom, and this spectacle, which might alarm or frighten him, he enjoys. He enjoys it so much that going to the zoo is one of the pleasures of childhood, or is thought to be such… ”

This is how Jorge Luis Borges and his amanuensis Marguerita Guerrero opened the preface to their Book of Imaginary Beings in 1957. “Let us now pass,” they continued, “from the zoo of reality to the zoo of mythologies, to the zoo whose denizens are not lions but sphinxes and griffons and centaurs.” In 2011, this book, a kind of alphabet of imaginary creatures from the ancient mythologies of Greece, India and China to the contemporary literature of the fantastic, became the object of a Kickstarter campaign to create forged copper masks of every creature within its pages. It reached its two grand goal, easily, and with change.

Now, five years later, a new exhibition at Sadie Coles’ Soho HQ takes fresh inspiration from Borges’s compendium. The Book of Imaginary Beings After Jorge Luis Borges comprises a set of 32 drawings in coloured pencil by the Athens-born artist Christiana Soulou. First presented at the 2013 Venice Biennale, under the larger rubric of ‘The Encyclopaedic Palace’, where they sat alongside other Borgesian creations by Levi Fisher Ames and Jakub Julian Ziólkowski; the project has since expanded beyond the original set of 23 to encompass even more creatures from Borges’s bestiary – and beyond.

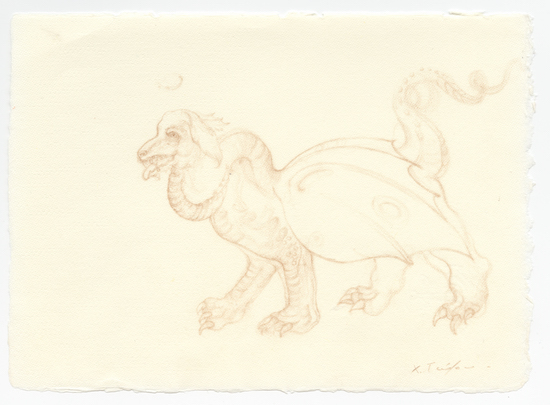

For though Soulou has sketched both the Griffon and the Chimera amongst other beasts enumerated by the Argentine author, she has also extended and diversified his menagerie in a number of surprising ways. Borges’s references were predominantly literary. Alongside Pliny and Ovid, we find references in his book to beasts imagined by Kafka, C.S. Lewis, H.G. Wells, and Flaubert. These authors Soulou largely eschews. In their place we find two Monstres after Raphael, scabrous beasts repeated in red and pale blue, abstracted from the Renaissance master’s oil painting of St. Michael Slaying the Devil, as well as a Dragon after Uccello, untethered from the Pratovecchio-born painter’s c.1470 canvas of Saint George and the Dragon. With these sketches, Soulou draws Borges’s project outside of literature and into the history of art.

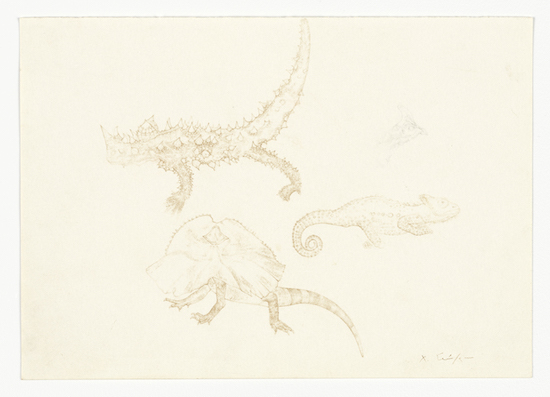

Christiana Soulou, Thorny Devil and Dragons, 2013, Copyright the artist, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

While these direct references remain within the Italian tradition, Soulou’s most obvious artistic forebears belong to the northern European heritage of Raphael’s near-contemporaries Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein. Soulou herself finds in Dürer and Holbein’s drawings “the union of representation with the abstract expression of a line that constitutes a pure formal value,” as she writes in an essay in the book accompanying the exhibition. “In their drawings the line is independent from its nature of representation,” she continues. “It does not have a limiting contour nor does it serve the thing depicted. It goes beyond its purpose of representation. The form is sublimated by the line and is pushed towards its most abstract sense.”

The above quote points to the abstract element in Soulou’s own drawings. Though figurative, for sure, the draftsmanship depicting these fantastic beasts is at times so fine as to almost evanesce into blank surface of the page. In so doing, the white space of the paper becomes activated, attention is drawn to it and it ceases to operate as a mere neutral plane or unfilled background, becoming rather a kind of force in itself, a quasi-utopian space forever threatening to engulf the species there housed. At the exhibition’s private view it was common to see people craning their neck right up to the page to get a better view, but looking as if they themselves were about to be sucked into the void of the page. I found myself reminded of an old Doctor Who episode from 1973 called ‘Carnival of Monsters’ in which the Third Doctor (played by Jon Pertwee) encounters a travelling showman named Vorg in possession of a ‘miniscope’ with which he has captured, reduced, and held in suspension innumerable species from different planets and timelines.

As Soulou notes, for all Borges’s wealth of description and the fulsome research material gathered on his improbable beasts, what remains “impossible to think” in his text is precisely “the site itself, where they could be acquainted.” For the heterotopic non-place of language, in which Borges is able to position his monsters, if not quite in concert, then at least side by side, Soulou substitutes the blank space of her paper upon which her own beasts are frozen, as in Vorg’s miniscope, bringing them into a space at once real – inasmuch as the paper itself is a real, physical material occupying actual space in the gallery – and at the same time impossible.

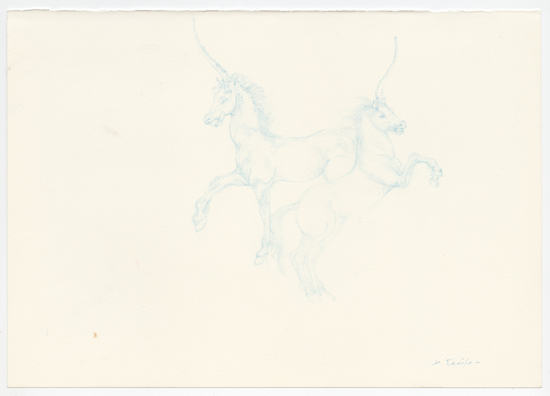

Christiana Soulou, Monstre, 2015, Copyright the artist, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Which brings us to what may be the oddest thing about Soulou’s imaginary menagerie. Many of the creatures depicted in her drawings are not imaginary at all. Sure, she has her unicorns, her pig-dogs, and her talking lions. But hung by their side we find an eagle and several small deer. Borges, in his preface, had reluctantly admitted, “Anyone looking into the pages of the present handbook will soon find out that the zoology of dreams is far poorer than the zoology of the Maker.” By introducing creatures into her pictures, not from the source book, nor any other fiction, but from our very own world, she succeeds in animating this statement of Borges. Somehow it is the real, familiar animals that now seem strange and uncanny.

As Flash Art International’s Donatien Grau remarks, in another essay from the catalogue, “such creatures as the eagle, the lion, or the deer do all exist in actuality. By bringing these together in the same series, even though they are not imaginary, even though they were not evoked by Borges, Christiana Soulou invites us to re-think what a book is; what imaginary means; and what beings are.”

Christiana Solou’s The Book of Imaginary Beings after Jorge Luis Borges is at Sadie Coles until 20 February