Christian Boltanski, Crépuscule (2015)

We leave our world, as Christian Boltanski would have it, seeing an array of blue light-bulbs that reads ‘Departure’. This sign announcing the work’s title hangs over the entrance to the French artist’s show, suggesting the beginning of a journey – our exit from the earthly realm and entrance to Boltanski’s very own underworld.

We have left the airy open spaces of the oil-refinery styled museum, with its wide balcony and spectacular views of the great grey city, to find ourselves in a claustrophobic, deeply stygian, gloom. All we can hear is a man coughing vigorously. His tussive bursts are relentless and then, on a screen, we see his slumped figure out of the darkness as blood pours from his mouth; he’s exsanguinating. This is Coughing Man (1969), a short video loop that sets the grim tone here. Faire son temps, Boltanski’s present exhibition at the Pompidou Centre, is a disturbing experience, a bit like a ride on a ghost train as a kid – part exhilaration, part wind-up, and an entirely fearful trip.

Boltanski is quick to make his own presence felt. Monochrome images of him taken at various ages are projected onto a plastic curtain that see him age before our eyes (In the Meantime, 2003). Then comes the first of many works about death. Boltanski is half in love with easeful death but that other half wants to rescue us from it, redeem us from erasure. He is the great worrier about memory, about how we are forgotten.

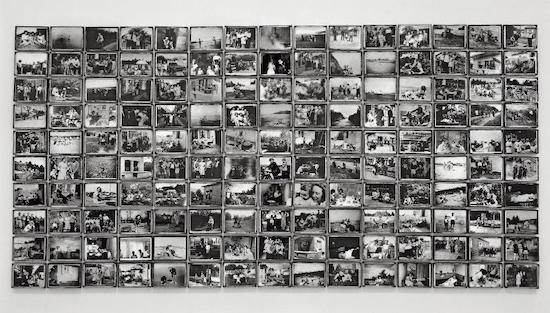

And here’s a group of photographs that throw you. They were clearly taken some time back; many of the children here are now dead. But they look happy enough and that’s Boltanski’s point: they were joyful then but that was all too fleeting. This is a work from 1972 and it is called The 62 Members of Club Mickey, 1955, The Children’s Favourite Photos. Our transient memories of happiness, that time now all gone. Boltanski wants to preserve something of them. He wants to say those moments did actually happen; they did really exist.

Then there is perhaps his most famous work, The Reserve of Dead Swiss (1990). Before digital photography, images of the recently deceased – as seen in newspapers, or on cemetery headstones in (predominantly) Catholic European countries – were sad affairs. The dead soul was captured as if they had just been told they were about to die: their faces in vague shock, eyes and mouths fading to black holes. Boltanski is keenly aware of their fascination, their horror, and so he used some shots that he’d collected from the Swiss newspaper Le Nouvelliste du Valais.

Christian Boltanski, Animitas Blanc (2017)

Why the Swiss? Well, why not? The die like everyone else and the dead people we see here were all things to all men – wealthy or skint, devils or angels. Boltanski also knew that viewers would be quick to see these constructions as altars. They might understand them as a plea for some kind of intervention, the Catholic idea of the faithfully departed waiting for petitions, silent and calm, for prayer in order to release them from purgatory, perdition, and be led to perpetual light and life. There’s also the idea that the neutral Swiss – ducking out of WW2 whilst stashing Nazi gold – had somehow escaped fate. They had not. In a sister work, Reserve: The Dead Swiss (1991), their photographs are now stuck onto towers of metal boxes that reach upwards to… where, exactly? Heaven or nothingness?

And then there’s the Holocaust. It has long been recognized that this is Boltanski’s central concern but it has taken me decades to work out exactly how his works actually achieve this. And then I looked again at those dead Swiss: how Boltanski lights their faces. His use of stark interrogatory single bulbs is also well known. But this time it was the configuration of the lamps that struck me, the S-curve of their connecting piece, their grey bowl-like shades, and how these forms mirror exactly the shape of those rusted lamp fittings that, to this day, line the barbed wire at Auschwitz.

How could these works not in some sense refer to the key trauma of humankind? The industrialisation of mass death. Boltanski made another set of works after discovering a photograph from a Jewish school in Berlin. Reserve Hamburgerstrasse (1992) and The Black Portraits (1993) show images of smiling children destined for the camps. He revisited these in 2016 with After. Here the young faces are printed on fine voile curtains, degraded in places and reminding us that even images of ourselves will inevitably disappear.

Christian Boltanski, Album de photos de la famille D., 1939-1964 (1971)

Again in honour of lost children we see Reliquary (1990), a work directly about the Shoah, where Boltanski takes images from a 1937 Vienna high school yearbook and has these glaringly spot-lit by clip-on lamps. These sit on rusted tins like urns. Some of the images here aim to break your heart, as with The Last Dance (2004), that sees a happy Jewish Romanian couple in a clinch. They are escaping on board a ship bound for Istanbul that was subsequently torpedoed.

As for his own relatives (and the injustice of their vanishing) My Dead (2002) is a sequence of plaques bearing only the dates of those close to him. His memorials become increasingly monumental and Human, from 1994, features 1,200 black-and-white facial shots of people between 1970 and the year of its making. All human life again is here, even old Nazis. Staring at the faces we have no idea of their past – were they victims, collaborators, or perpetrators? Were they mere by-standers in life – the passed over?

More recently his work has taken on an explicitly planetary dimension: it is not just we that die, the Earth will too. Mysteries (2017) is a three-screen video work featuring, from right to left: an empty Patagonian seascape, three enormous missile-like metallic sound sculptures by the sea, and a whale skeleton on the beach. Wind creates an eerie noise like whale song. Everything will, as WG Sebald implied, turn to dust just like the rings of Saturn.

Boltanski is the visual poet of the preterite. We leave with another lit sign, this time in red, which chimes with how we began: Arrival (2015). Like the show, like Boltanski’s work itself, the message is: faire son temps – you’ve had your time.

Christian Boltanski, Faire son temps, is at the Pompidou Centre, Paris, until 16 March 2020