On the 15th of July last year, as a faction from within the Turkish armed forces tried to wrest power from the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in an attempted coup d’état, Cevdet Erek was in Aydin Province, in the west of Turkey. “I found myself in a huge Greek settlement, alone,” he tells me. “Then, in this no-longer-functioning amphitheatre, I heard crickets – a concert.”

So you were standing there, I start to say by way of clarification, in this ruined amphitheatre in Priene when you heard about the coup, and that’s when you were struck by this chorus of crickets?

“Not struck –” Erek corrects me, “but I chose to accept it as a concert.”

The ruins of the ancient city of Priene are located a short hop west of a village called Güllübahçe Turun in the Söke district of Turkey’s Aydin Province. In the fourth century BCE, Alexander the Great himself had sought to make it a model city, the very image of Hellenic town planning. It was laid out on a grid system, cleverly integrated into the slope of the neighbouring Mycale mountain, carefully portioned into religious, private, and public spheres, its extensive array of temples and civic buildings designed according to the natural order of Pythagorean numerological principles.

But by the first century, Alexander’s dream was already falling apart. Silt from the Maeander river was making the inlet uninhabitable. People moved on. Its proud ionian architecture was neglected. Today, it remains one of the most well-preserved of ancient Greek cities. In some respects, the centuries of neglect saved it. Nothing got updated. But now the city is crumbling. “These ruins are ruins,” as Erek says, “because many people don’t care about them. But they are there because they are strong, otherwise they would just disappear.”

Picture him there for a moment: surrounded by the decaying remains of a once-mighty civilisation, knowing that his home town is in chaos, but standing alone there in the middle of the amphitheatre, in almost total silence, with just the crickets to sing to him.

Ten months later and Erek is preparing to open his intervention upon another ancient structure, what he calls the “well-taken-care of ruins” of the Venetian Arsenale. The Venice Biennale is one of the few art festivals in the world to continue with the system of national pavilions, a kind of colonial hangover from the days of Great Exhibitions and World Expos. In recent years, many artists and curators have struggled against the system in various ways – from Hans Haacke unearthing the German pavilion’s Nazi past to 1993’s Biennale director Achille Bonito Oliva encouraging curators to mix homegrown with foreign talent. But the system struggles on and artists are left to struggle with it, for better or for worse.

For Erek, representing Turkey this year is “difficult, for sure. Because the national pavilion is already something which comes with a heavy [burden] – but also in such a year in Turkey…” Still he approaches his burden with a shrug of sanguine resignation. “I have to say that, I enjoy that also, because it’s a challenge. It’s a problem. You have to think about solutions. The work that I’m doing is mostly trying to find a solution to a spatial problem. But i like that also, because we artists, we want to show our work. we want to prove that we can come up with a new language, new solutions.”

“I’m doing my best,” he continues, “to do something which adds to the culture of free speech in my country. But also, as an individual, we all have some things in our lives that make us something other than a Turk or a member of a society. It’s difficult, but I don’t complain. It’s a chance – but then you have to pay with your –” he pauses momentarily, “– I don’t want to say ass, but with your brain, sleepless nights, endless communications, politics, of course…”

As to the content of Erek’s intervention, he is – so far – remaining tight-lipped. At the press conference given to announce his proposal, he refrained from giving a description of the work or detailing its means and methods. Instead he invited the gathered press “to imagine a scene: there is a fenced ruin in the distance with a guard inside of it who should not leave during the day. The guard, while walking in silence, notices a visitor who carefully peeks around and the concert of thousands of crickets thanks to the visitor. This duo who try to talk to each other at a distance, briefly cry out at the same time from the ear pain caused by a violent noise that occurs out of the blue. Then, at night, in another place as the guard tries to suppress the ringing in her ears by opening the window two fingerbreadths and the noise a notch, enters an alarm sound: ‘viyuviyuviyuviyu.’ Then she tries to imagine again in the same order by going back to the beginning.”

This curious fairytale, Erek tells me, has its origins in the strange solitary experience he had in Priene some months before. The story became a kind of “preparation to the installation” while at the same time “not making a description of the actual work.” Somewhere, somehow, encoded within this narrative, there are “some of the main references/sources for the work”. But where, how, or why – who can say?

Born in 1974, Erek studied architecture, not art, at university, graduating from Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts in Istanbul in 1999. Later, he took a master’s degree in sound engineering and design at the Center for Advanced Studies in Music (MIAM) at Istanbul Technical University. Meanwhile, he has been the longstanding drummer in Turkish rock band, Nekropsi, a group that long left their thrash metal roots behind to veer into ever stranger, more hard to define territory. As an artist, his own work somehow manages to combine this peculiar skillset into a sharp pronged tool for the investigation of time, space, and, and place.

His Ruler and Rhythm Studies, which have been ongoing since 2007, translate time into space, replacing the centimetre increments on a series of perspex rulers into notches marking the days, weeks, and years – as well as vaguer, harder to define temporal units. One marks out the distance between Erek’s birth in 1974 and 2008, the year he made it; another materialises the passage, ominously, from “Now” to “End”. At Bristol’s Spike Island, in 2014, he used networks of directional speaker system to map the space of the gallery in an architecture of rhythm, pulsing to the beats of house and techno.

For last year’s Sydney Biennale, he soundtracked a former guards’ barracks on Cockatoo Island with a pounding beat structured to the timescale of a century of industrial action, slowing down in protest here, abruptly stopping for a strike there. The work was inspired, he tells me, by an experience on the Brussels Metro, in which the halting journey of a few stops – ten minutes travel somehow stretching to half an hour – had an immediate and palpable effect on the psychology of the passengers.

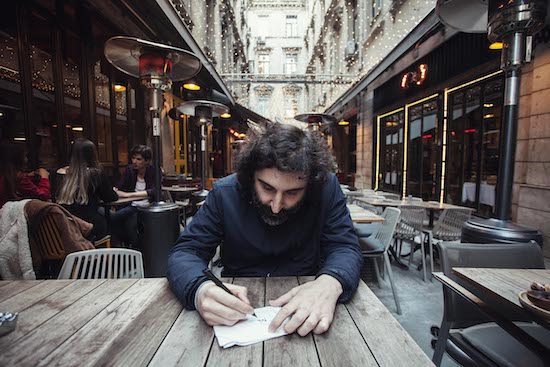

Talking to Erek for this piece proved an equally confounding experience – though through no fault of his. We started off talking over a noisy and glitchy Skype connection, then switched to chat when the problems with that proved insurmountable – but even then the dialogue was strangely stilted, with bits of the answers to one question turning up after I’d already asked the next, sentence fragments split off from each other, intended meanings passing each other at high speed over submarine fibreoptic cables, somehow always failing quite to connect. At one point, the interview is paused as Erek tries to find another cafe to sit in, with a better internet connection.

Finally I say, “it’s funny, in a way – we’ve been talking a lot about time and rhythm, and all the way through, the very thing that’s been making this interview kind of a little bit awkward is the peculiar sense of temporality you get with Skype, a technology that always presents itself as ‘real time’ but is really much more complicated.”

“Yes!” he types. “Perfect – and in chat, text replaces speech.”

Suddenly I hear the lilting trill of minor key boops that signify a video call coming through. There’s Erek, bearded and hunched over a table in a Venetian coffee shop. He tells me he has another clue for the Turkish Pavilion. “I’m not making another work which stresses sound with other representations of a temporal unit,” he says. “There is another series of works called sound ornamentation works, where I am imagining making ornaments using sound.”

“if you think of traditional architectural ornamentation,” he continues, “there is always images and words. So in sound, that has to be speech. So, if you are an idiot like me, that tries to represent architectural ornamentation through sound, you have to use speech.”

He wont tell me anymore, preferring to preserve the surprise for anyone who might visit the Arsenale over the coming weeks. “I don’t watch trailers,” he says, “before going to a film.”

Cevdet Erek, ÇIN, will be in the Turkish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, from 13 May to 26 November