There was a time when art and design weren’t deemed to be too good for the working classes. In 1962, designers of the Stifford Estate in Stepney bought a Henry Moore to serve as the proud centrepiece of their new community, while estates like Park Hill and Trellick Tower were among the most innovative architectural projects of their time, with generous floorplans, floor-to-ceiling windows and balconies so big that social housing tenants could dine al fresco. Now, many of the 60s most forward-thinking estates are either facing demolition after years of underfunding or have been sold off and taken over by the middle classes, and campaigners have had to go to court to stop cash-strapped Tower Hamlets flogging off the Henry Moore.

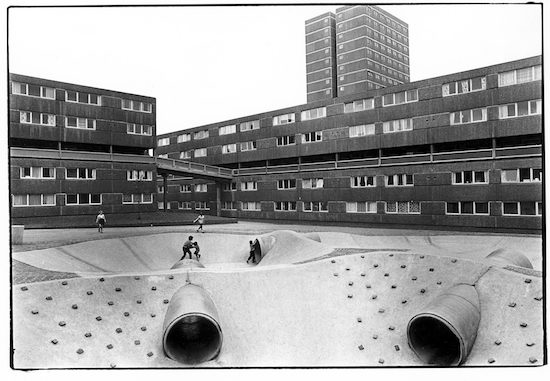

In the increasingly specialised world of urban design, architects are now seen solely as designers of buildings, but they were once interdisciplinary artists who could create anything from a citywide masterplan (see Le Corbusier’s proposal to ruin Paris) through to the detailing of a tower block’s signage. Mies van der Rohe designed furniture to compliment his skeletal steel buildings, while Iannis Xenakis built the Philips Pavilion at Expo 58 and composed the electroacoustic music performed inside it. When creating the radical housing projects that would define postwar Britain, architects like Ernő Goldfinger, Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith micromanaged their projects, drawing up plans for parks, sculptures, pubs and playgrounds that reflected a consistent social ethos. The playgrounds they built seem to be microcosms of the overall projects, with forms, textures and visual references that echo the massive buildings they serve.

To our eyes their playgrounds look like death traps, and they’ve all been demolished except for the one at Goldfinger’s Grade II listed Balfron Tower, now cordoned off from the hands of children or developers. Despite their central position in these densely populated complexes, surprisingly few photos exist in RIBA’s archives – a challenge to architectural collective ASSEMBLE who have worked with artist Simon Terrill to create The Brutalist Playground. The show, which has opened at Park Hill’s Scottish Queen after a run at RIBA HQ in London, sees elements of these playgrounds recreated on a 1:1 scale in foam, from a utilitarian lookout tower to a complex of underground tunnels with moveable geometric shapes scattered around the gallery like Tetris pieces.

“I think that the structures built during the postwar period demonstrate that society was more able to conceive alternatives and imagine the world anew after the destruction and failure of the recent past,” Jane Hill of ASSEMBLE tells me by e-mail. “It was also a time when playgrounds formed part of the landscape and broader architectural ideology, therefore being a concern of the architect to design. In this way playgrounds were part of the built environment, not separate to it.”

Housing constructed using the YDG (Yorkshire Development Group) system, Tony Ray-Jones / RIBA Collection

The show’s headline act is a lopsided disc nicknamed The Flying Saucer, pinched from Pimlico’s Churchill Gardens estate. Held in the air on a pedestal, the disc tilts violently like its permanently trying to eject unwanted visitors. It’s about two or three degrees steeper than you’d think possible and standing on it feels dangerous, even though it’s no longer made from skin-shredding concrete. Photos show that the original – long since erased from the estate – was much higher off the ground, with a concrete replica of the Giant’s Causeway leading up to it, looking like the arcade game Q*bert draped in 60s monochrome. Unfortunately that bit’s been left out, probably because the saucer barely fits in the room as it is.

Another highlight are the tunnels from Park Hill’s own doomed playground a few metres away. Added to the show with its move up north, they’re claustrophobic and slightly oppressive, even when rendered in brightly-coloured foam. Running deeper than you’d expect, these hidden passageways presumably became a go-to place after dark for estate teenagers in need of privacy. This is Sheffield, the city of Threads, and as Jarvis once sang: this is hardcore.

There are some rules in the playground – you have to take your shoes off before you’re allowed to play, like a transition ritual. In the gallery environment we’re all familiar with (coffee table books, tasteful typefaces, Scandinavian furniture), the show’s visitors seemed unsure how to let go and play like they did as kids. Fortunately, gallery attendants were actively egging people on, asking them to run instead of walk (!) and talking me into an ill-advised sprint down the saucer, my legs buckling beneath me when I made my own crash landing.

Illustration demonstrating the importance of both indoor and outdoor recreation to adults and children alike, RIBA Collection

Play as participatory art has been done before, notably by Belgian artist Carsten Höller and his slides for adults (a new one, attached to Anish Kapoor’s Orbit, just opened). This is different, falling somewhere between art, play and a historical recreation in which the audience relive childhood moments as oversized giants. Although it’s essentially a recreation of somebody else’s work – think of it as the V&A Cast Courts for the 0-10s – there are little moments of artistic intervention. I don’t know if it’s by happy accident or design, but the lookout tower is only slightly shorter than the gallery’s ceiling (concrete, of course), forcing you to crouch when you’ve reached the top instead of standing tall beneath the blue skies of the East End. Is it a nod to how these once visionary schemes are now seen as limiting the prospects of the people they were supposed to liberate?

Today’s playgrounds are built by specialist companies and come prepackaged out of the box, with the same slides, swings and seesaws in every town, as well as those crappy pedal roundabouts that never seemed to work when I was a kid. Like identikit high streets with their predictable sequence of banks, Primarks and coffee chains, playgrounds are part of an increasingly homogenised built environment that leaves all of Britain looking, well, like the rest of Britain. To their credit, ASSEMBLE aren’t just content with recreating the idealism of the past – they’ve had a proper go themselves with the Baltic Street Adventure Playground in east Glasgow. Looking less like a playground and more like a wasteground, children are free to construct, utilise and alter the environment as they wish using any materials they can find: spades, saws, pipes and branches to make campfires with.

Public housing, Runcorn, Cheshire, RIBA Collection

“Modern playgrounds tend to be risk adverse,” Hill tells me, “favouring safety over the child’s right to experience the world through new and challenging ways during play. Safety concerns largely appear misplaced, with contemporary playgrounds seemingly offering a ‘safe’ environment which, more often than not, despite the use of bright colours, is no safer than a lot of other environments children could be playing in. Playgrounds today also dictate how a child should play, whereas in Glasgow we tried to create the setting and tools to facilitate children investigating how they wanted to play for themselves.”

Baltic Street is a logical evolution from the brutalist playgrounds, whose minimalist structures allowed for almost unlimited role-play. Take the lookout tower, which could potentially serve as a pirate ship or a castle’s keep, or more darkly, a war bunker (it was presumably inspired by WWII pillboxes). If, as Brian Eno reckons, the coming era will be one of almost unlimited creativity once we’re freed from the drudgery of work, the need for children to learn to play and create will become increasingly central to good education. Both the architects of the 60s and their modern day counterparts at ASSEMBLE show that these vital features of the community work best when they respond to the environment around them and the needs of the children using them, rather than being airlifted in like an alien visitor. Maybe go easy on the concrete though.

The Brutalist Playground is at S1 Artspace until 11 September