Haywain with Cruise Missiles. Peter Kennard. Photomontage (1981)

“Community photographers want to give more than charity or expose social injustice. They believe that people can use photography to make their own demands and help to make them free.” Camerawork, Issue 13

In the last few months, there has been considerable interest in the ‘Tape/Slide Newsreel group’ archive, recently unearthed in the historic Rio Cinema. A Kickstarter project has been created to publish an oral history book exploring thousands of photographs taken by local unemployed residents. But this group is just one of many in a forgotten movement, where, amidst political fervor and economic crisis at the tail end of the ‘Golden Age,’ radical collectives across London strove to democratise photography.

In a smartphone society where a digital camera is just a swipe away, it is easy to forget the barriers blocking access to the medium fifty years ago. Equipment was expensive, manual cameras were complicated and developing the film took practice. Before the digital age, the workers’ photography movements of the Great Depression had created a precedent for a collective photo-theory, promoting photographic literacy and giving a voice to the unrepresented. Responding to crisis in a similar vein, the collectives of the 70s turned their cameras away from an industry dominated by commercialism. They counteracted the corporate-art-machine through principles of cooperation, representing marginalised peoples and sharing their expertise with the wider community.

Inspired by agritprop and consumed by a burgeoning punk mindset, many artists of the 1970s were committed to distributing art by circumventing traditional hierarchies. Aided by increased funding from the Arts Council, the combination of this DIY ethos with post-68 grassroots movements, resulted in a proliferation of radical photography collectives. Public workshops flourished as a growing frustration with existing institutions led to the creation of alternative forms of production and public engagement.

The Blackfriars Photography project recorded political activity in Lambeth, Photoworks Westminster, an educational group committed to engaging in local politics was set up along with a community darkroom, and the East End became a national hub for subversive photographic work.

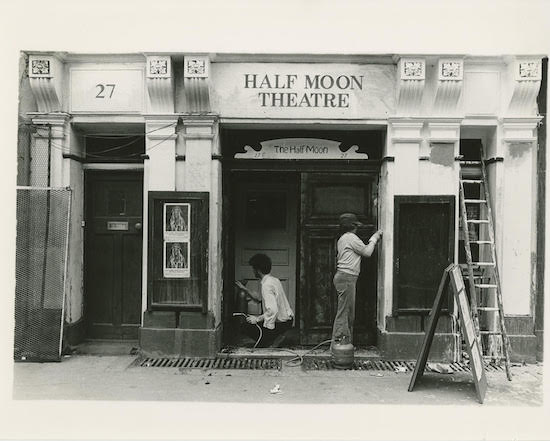

The East End has a rich political history and throughout the 70s it was still a stronghold for community activism. In the building of a former synagogue, the Half Moon Workshop was founded by American photographer Wendy Ewald. The studio housed one of the most influential co-operatives within the movement and joined a growing network of alternative, grassroots cultural spaces in London’s East End. The workshop democratised the image by bringing production and consumption closer to the community. Advice was given on using the camera as a tool for activism and space was set-aside for local residents to exhibit and use a public darkroom.

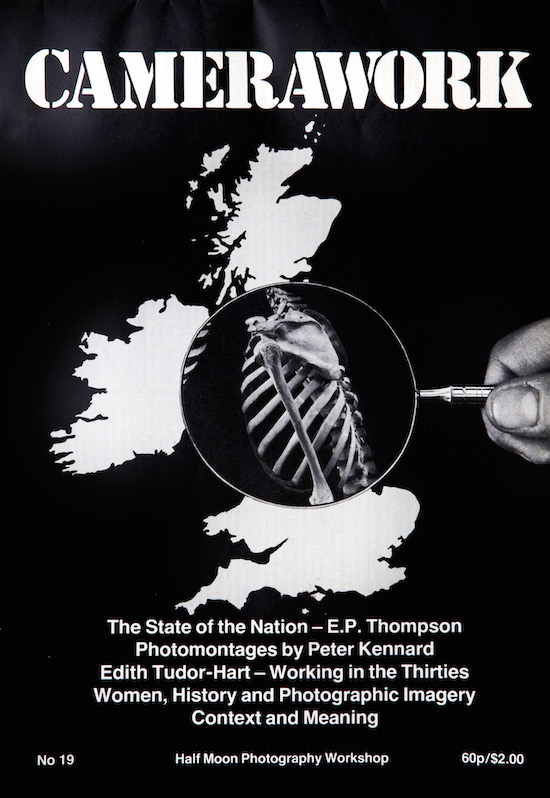

Pete Kennard/Camerawork

Perhaps a tongue-in-cheek reference to Alfred Stieglitz’ elitist publication of the same title, Terry Dennett and Jo Spence founded the influential magazine Camerawork. Born out of the Half Moon Workshop, the magazine posited itself as a countercultural alternative to mainstream photojournalism, questioning the social purpose of the practice and deconstructing established principles of representation. Pioneering a move away from straight photography, the editors chose to incorporate photomontage and text. A distinct style characterized by Pete Kennard’s provocative ‘Haywain with Cruise Missiles’ photomontage accompanying EP Thompson’s famous ‘State of the Nation’ essay in issue 19. Using A3-sized pages dominated by deep blacks, the magazine’s striking visual commentary ranged from the Troubles in Northern Ireland to the Battle of Lewisham in ’77.

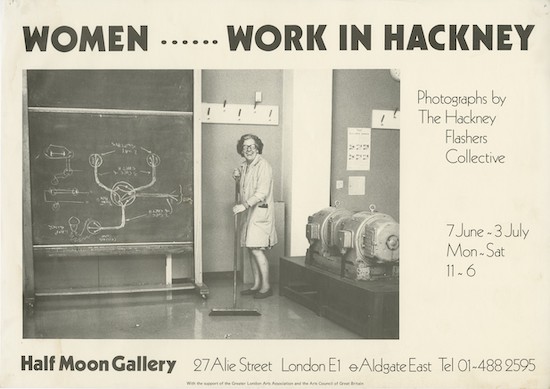

In 1970, the equal pay act passed through Parliament and the first meeting of the Women’s Liberation Movement was held at Ruskin College, beginning a new wave of feminist consciousness. Centering the debate on the intersection of class and gender, the WLM demanded equal pay and equal opportunities in the workplace, the right to abortion and universal childcare. Their influence extended to photography, as six years later, the Half Moon Photography Workshop staged one of the first exhibitions to tackle politics from an overtly feminist perspective, entitled ‘Women and Work.’ The project confronted the sexual division of labour using minimalist black and white photographs accompanied by films of women in the factory, sociological text and interviews.

A pre-cursor to the Guerilla Girls, the all-woman agritprop collective who formed out of the exhibition, the Hackney Flashers made demands for working class women’s rights. Allowing any woman to join, the group was open to inexperienced photographers and governed by a horizontal structure that rejected individualistic practice. In 1978, they staged their second seminal exhibition, Who’s Holding the Baby? Taking inspiration from anti-fascist collage artists Hannah Höch and John Heartfield, the multi-media show montaged appropriated imagery, cartoons, text, and photographs to intervene in the local and national debate on childcare. A year later, the exhibition was included in the Hayward Gallery’s show, Three Perspectives on Photography. The exhibition remains highly apt, seeing as there is still very little provision for childcare in Britain.

The coalition of art, politics, activism, and feminism began to deteriorate with the rise of Thatcherism and the subsequent retraction of funding. Although briefly mitigated by the GLC, the demise of many projects occurred during the mid-80s.

Mike Goldwater/Hackney Flashers/Four Corners Archive

Cultural research on the 1970s and early 80s has often been too focused on bolder subcultures, overlooking the importance of the community-workshop movement and what the critic John A. Walker called the “re-politicization and feminization” of art. Demystifying the medium by giving a platform to previously excluded ‘amateurs’ and by instigating a radical critique of the photographer’s role, the movement had a lasting impact on the consciousness of British photography.

Although the age of community-based photography collectives and adequate funding for the arts is over, their principles are more salient than ever. As our lives become increasingly saturated with manipulative visual culture, questioning the social context of a constant stream of images could not be greater. By asking who images are currently produced for and for whom should they be produced, this forgotten history teaches us the power of inclusion, the importance of documenting community struggle and reinforces a belief in the camera as a universal tool for emancipation.