Eric Pauwels, Violin Fase (1986). Installation Photograph by Damian Griffiths. Courtesy of the artist, Argos Brussels and CGP London

There is a moment in Eric Pauwels’s 1986 film Violin Fase when the lone dancer on screen, in the midst of a frenetic, seemingly interminable performance, suddenly yells out "jesus christ!" as if in revelatory amazement at her own endurance. Her exclamation is a crack in the surface of the film, a chink in the armour of the set-down choreography and ordered musical notation. With the surplus of a human body in the mix, Pauwels captures the possibility of total collapse or open revolt. Rhythms – it seems – are there to be upset.

We live in a time when our shared sense of being rooted has more or less crumbled to nothing. At best, this has meant the dumping of outmoded convention and the real possibility of toppling hegemonies; at worst it means the absence of anything to grab onto as the ground falls away. Alongside love, fear and various other behemoth emotions perpetually un-riddled and digested by art, sits a quieter notion that is always at the forefront of both personal and collective consciousness: a feeling of precarity, that agonising and exhilarating catch point before the rescue or – more likely – the fall.

This is the feeling encapsulated by BRINK, a scant, methodical show curated by Matt Carter and currently installed in Dilston Grove – a de-consecrated former mission church in a corner of Southwark Park. It features only six works by as many artists, but each speaks with an unnerving immediacy to the show’s conceit. Avoiding both the build-up and the crash, it instead bottles the energy of an uncanny limbo state between the two.

The space – which is low lit and cold enough that you can see your breath – is filled with the sound of Steve Reich’s 1967 piece Violin Phase, an undulating process loop that seems unable to resolve itself. This is the soundtrack of Pauwels’s aforementioned film, which observes the performer at such close proximity that the camera is almost knocked to the ground. This nearness creates an uncomfortable relation to the solo dancer on screen, who is engaged in movement reminiscent, in its casual shabbiness, to Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A – another dance work which dispensed with spectacle in favour of depicting a body simply being a body. The result is an empathy that you feel in your flesh.

As the piece winds on it becomes an endurance test for viewer and performer alike. Another turn or sequence or repeating phrase of the music seems impossible and totally beyond what a body can take. But the rhythm persists, the lens flares, and the camera becomes a dizzy, watery eye.

Watching Chris Saunders’s video installation Long Walk (1994) is like remembering a nightmare: legging it down corridors toward hopeful double doors only to find that they open out to more of the same – and on and on. Referencing Richard Long’s iconic land works, Saunders swaps a bucolic footpath for an all too familiar landscape of anonymous office interiors, traversing conference tables and miles of nylon carpet while dodging abandoned filing cabinets which make odd monuments in otherwise empty space.

The scene is tinged with post-apocalyptic unease, forming a hypnotic loop that, like Reich’s music, fails to resolve. There’s the promise of blissful exit via the 10th floor boardroom window or the glass sliding doors of the lobby, but then the scene cuts and the walk begins again.

On the floor in front of the projection is a sinister faerie ring of mounded objects – in the half-dark they resemble de-skulled brains or Trump wigs. On closer inspection they turn out to be balls of carpet fluff, apparently scuffed up en route during the making of the video. A man made relic of the walk.

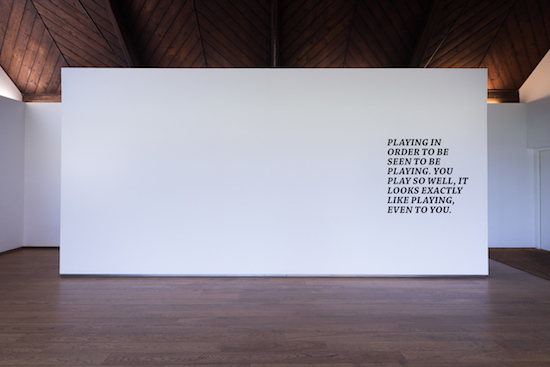

Gil Leung, Playing Text (2015). Installation Photograph by Damian Griffiths. Courtesy of the artist and CGP London

It makes sense that an exhibition aiming to capture an intangible feeling would lean predominantly on moving image, but works by Lucy Skaer and Graham Dolphin give necessary balance with objects that belong more to the head than the body. Dolphin uses drawing to explore the way that ephemeral things become burdened with the meaning we give them. Under the hot glow of what incidentally (but fittingly) looks like a writing desk lamp, is Final Note (Sylvia Plath) (2012), a ghostly pencil drawing of a torn notepad page featuring the words “Call Doctor Horder”. In the circumstances of Plath’s suicide this instruction was futile, but it speaks to the knife-edge moment between life and death, the meant and the accidental, between what could and could not be helped.

Skaer’s Solid Ground – Liquid to Solid in 85 Years, (2006) is the exhibition’s most curious work – a table of indeterminate coloured objects that could be archaeological detritus, machine parts or nursery toys. As becomes apparent from their cracked open interiors they are actually Rorschach blots spun into three-dimensional objects – Freudian playthings. They are ominous, fragile-looking and strangely beautiful. All these sensations are amplified when you consider that these objects might represent the imagination of paranoia or fear made solid, to be held in your hand or maybe dropped and broken.

Lastly, under Dilston Grove’s low cupola, is Jean-Paul Kelly’s Movement in Squares (2013) a two channel video that pairs an exploration of Op art works by Bridget Riley with single perspective footage of the interiors of repossessed properties in Florida. The clipped, authoritative voiceover attests that “the process of looking makes us more truthfully aware of the condition of being alive.” But the left hand screen, exploring rotting, abandoned domestic spaces, is evidence of how regularly we fail to look. There’s the suggestion of life – a gluey handprint studded with flies, a warning written on a mirror – but certainly nothing living.

On the right the artist’s hand flips through a catalogue of Riley’s recognisable works, often pawing or fingertip-scanning them as if they were braille. In this tension between sight and touch Kelly acknowledges the safe distance we keep from reality, highlighting the things we don’t see but can definitely feel.

Riley’s hypnotic, vision-bending works suggest the possibility of other registers – of something sublime or unsuspected lurking beneath the surface of the known. Over a close-up image of her tightly packed graphic loops, “repetition” the voiceover tells us, “is a visual amplifier” where systems of sameness find their own rhythms and begin to shift and change.

Lucy Skaer, Liquid to Solid in 85 Years (2006). Installation Photograph by Damian Griffiths. Courtesy of the artist, Stephen Friedman Gallery and CGP London

Throughout the exhibition these patterns and revolutions are in dialogue – the windmill circles of Pauwels’ dancer which seem oddly like moments of repose; Saunders’ quasi-mystical floor piece; the implied spin of Skaer’s almost-toys; the imagined, agonising wait while Doctor Horder’s telephone rings and rings.

In BRINK (like the revolving of an on-screen ‘spinning wheel of doom’ that might mean the total destruction of your endeavours) this endless movement speaks to held breath and physical strain. But it also shows that this repetition contains both a possible space for action and a mode of rescue – like a regularly intoned mantra to keep you safe.

Whether on the brink of exhaustion, revelation or exit (from the room or from life itself), these works hint at the splintered cracks and slivers of light between one state and another. Performance and play become a foil for acts of subversion; reliable and familiar patterns become sites in which a different kind of revolution is easier to mask. Poignant and sharply curated BRINK is an apt exhibition for an era in which we are all edges.

BRINK runs at CGP / Dilston Grove until 17 April. On Saturday 16 April the gallery will screen Priit Pärn’s Hotel E (1992). www.cgplondon.org