Given the rocky few years that Museums Sheffield have had with spending cuts and budget black holes, hosting an exhibition by an artist like Bridget Riley feels like a statement of defiance. Riley, now one of Britain’s most respected living painters, made her name with a startling hybrid of Mondrian-style abstraction and brash pop-art, known, with a wink, as op-art. Her work uses shapes, rules, repeating patterns and colour to create what are usually called optical illusions, though that term feels insulting to her work, as if she’s somehow trying to trick her audience. Her art is always complex in its construction but amusingly simple in its composition. It’s childlike, even naive in a way.

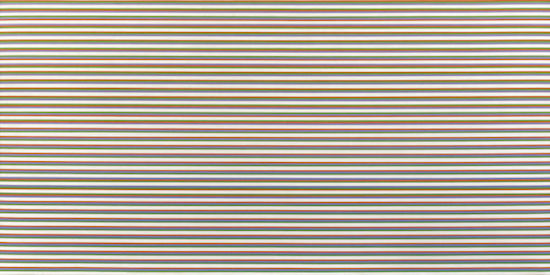

Late Morning 1 is part of a series of ‘stripe paintings’ that she’s added to from 1961 to present, and it consists solely of vertical bands of colour of repeating widths and hues. When it was made in 1967, it was part of a movement that shocked Britain by doing away with the figurative painting that we were still clinging to years after Pollock and Rothko had swept it away with a riotous tide of colour in America. It still shocks in 2016 but for a different reason – now we know that any teenager could create something similar in a few minutes using Photoshop, yet you can see the painstaking brush-strokes on the canvas, highlighting RIley’s ability to draw mathematical precision out of painting.

Venice and Beyond, Paintings 1967-1972 is a minimalist exhibition in more senses than one – it is possibly the smallest headline show at a public gallery I’ve ever been to. Two rooms with nine paintings, plus eleven preparatory studies. Actually, though there’s a suspicion that a whole wall of paper studies might be filler, these turn out to be as interesting as the finished paintings. Without figures, landscapes, or any other recognisable forms from our world, Riley’s paintings appear to have leapt out of the ether fully formed, as if created in a vacuum. But the studies act as a counterpoint to the apparent rootlessness of her finished work, with guidelines, scribbled notes and stubby pencil marks all on show. Like Richard Rogers turning the Pompidou Centre inside out, the studies put the invisible rules on display – they show Riley’s workings in the margin.

Her biggest canvases – there’s two in this show – are her most effective because their sheer size expands her work from being purely visual to something that begins to infiltrate your other senses. Stand close enough to one of her massive pictures (as every decent gallery will allow you to do) and her patterns and rhythms will envelop your entire peripheral vision. You might start to feel disorientated, nauseous, overcome with an odd sense of vertigo, and gallery chatter may sound distorted or oddly distant. It’s too easy to compare her work to the visuals of an acid trip, but you don’t necessarily need psychedelics to hallucinate moving lines and shifting shapes when her canvases are inches from your face. My friend had to leave because he was starting to get a migraine.

Rise 1, 1968 © Bridget Riley 2016, all rights reserved. Courtesy Karsten Schubert, London

After you’ve absorbed these then – oh, that’s it, barely five minutes after we arrived. Round the corner you can see one of Damian Hirst’s tossed-off spin paintings if you like. The Riley exhibition is showing in the Graves, the only public gallery with a permanent modern art collection in Sheffield city centre. It’s on the third floor (above the central library) of a vaguely monolithic building described by Pevsner as being in “an incomprehensibly insignificant position”. Opening hours have been slashed, with the gallery closed on Sundays, Mondays and bank holidays, and when it is open, it’s only for five hours a day. Meanwhile in London, a city famously devoid of art galleries, the Tate Modern opened its new £260m extension last week.

As a Sheffield resident, I’m glad we at least have the Graves, as well as temporary exhibitions in the nearby Millennium Galleries. But as the city’s flagship gallery, it’s not really good enough. Wakefield, 20 miles north of us, have had the brooding Hepworth since 2011, while down south, Nottingham folk have enjoyed the shimmering Contemporary since 2009. Sheffield desperately needs a larger gallery space, but before that happens, it’s possible that the limitations of the city’s spaces have forced curators to come up with a more imaginative show than they would have done if they’d had the Whitworth at their disposal.

With just two rooms to play with, it’s to their credit that they’ve avoided the temptation to do a grab-bag of the greatest hits, and have instead cleverly based the show on a pivotal moment in Riley’s career – her experimentations with colour in preparation for the 1968 Venice Biennale, as well as the development of these ideas in the early 70s. For an artist with so few points of reference for the unfamiliar viewer, this adds a welcome historical and social context, particularly regarding the history of women in art (Riley was the first woman to win the Biennale’s Painting Prize).

It’s perhaps unfortunate that of all the modernists, her style has been the one chosen to be imitated (badly) by a thousand web design companies and 90s CD covers. But most of the original work from the 60s still looks startlingly futuristic, even if some of the stripe paintings – which could double as wallpaper in a boutique hotel – haven’t dated as well. A piece like Little Diamond though feels utterly fresh, and still zaps the retinas with its fluorescent colours and near-digitally precise diamond patterns. Although a lot of her best known work is in black-and-white, Riley is a master of colour selection.

It’s interesting that while needing to do more-with-less as an organisation, Museums Sheffield have chosen an artist whose work uses austerity to strip away all that she sees as getting between the viewer and the essential essence of art. “For me, nature is not landscape,” she wrote, “but the dynamism of visual forces, an event rather than an appearance. These forces can only be tackled by treating colour and form as ultimate identities, freeing them from all descriptive or functional roles.”

Bridget Riley, Venice and Beyond, Paintings 1967-1972, is at the Graves Gallery, Sheffield, until 25 June