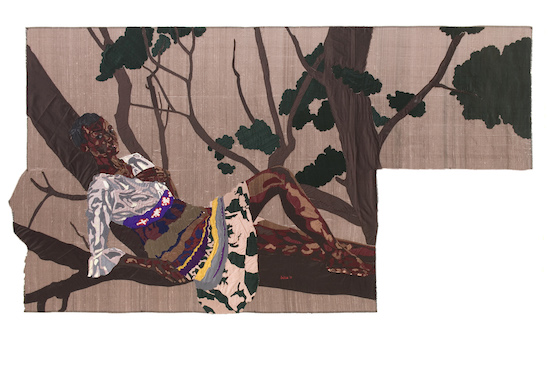

Billie Zangewa, Sweet dreams, 2010, Hand-stitched silk collage, 44.49 x 77.17 inches (113 x 196 cm). Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London.

There’s a tamed flame to Billie Zangewa collages. It reflects the artist’s specific feminist concerns and the way she views the world, how she thinks the female gaze might be perceived. She herself stars in several of the works here examining how she looks to the world as a woman, as a mother. Is it ok to look stylish when you’re tidying your boy’s bedroom? And so it’s a curve ball to be confronted at the beginning of the show by Game (2017) in which a white man in a black vest sits beside a swimming pool, staring out at us – his might be the male gaze personified. The ripples of light on the blue waters recall David Hockney; Zangewa is not afraid to depict the landscape of pleasure. Those deliberately gauche curves also reference Matisse. What looks like a pool cleaner does its lazy business while we wonder what the man is thinking. His pose gives little away as he sits forward into the sun. What is that game in the title? Is he trying to stare us out?

Zangewa is fond of leaving us with such questions. Her constructions leave gaps, tears in the fabric, that imply holes in the story, They ask you to complete the fictions and use your imagination to fill in the blanks.

Originally from Blantyre, Malawi, Zangewa grew up in Botswana. She got her Fine Art training in South Africa and is now based in Johannesburg. She makes works from textiles and thread. Her initial inspiration came after witnessing her mother’s sewing group. Zangewa has talked of the emotional support she recognised amongst the women and the “soothing repetitive nature of stitching” that she compares to group therapy. Working with silk, her collages have an obvious tension, a haptic appeal that must be denied: you can look but you’d better not touch. This is her first UK exhibition and it is that rarity in these loud times centred on an ever-demanding attention economy: a gentle affair that calmly claims your focus with its intimacy.

Paradise Revisited (2023) is the largest work in the show and sees Zangewa and her son sunbathing or maybe sleeping on recliners by another pool. The resort is otherwise deserted: mother and son at rest, at peace in another Eden. More restful imagery comes with Temporary Reprieve (2010) where a young boy (Zangewa’s son again?) lies asleep. The joy here is all in his posture: the artist captures the boy’s left hand awkwardly dorsi-flexed as kids pose when they’re out for the count. Meanwhile the right arm is extended, fingers bent in a near fist gesture in what could be imagined as a reference to the Black Panther salute. And there are rips again in the fabric reminding us that nothing lasts forever, that rest is only fleeting, as Zangewa’s title has it.

Sticking with feminism there’s a jokey dig at the idea of the Supermum with Everywoman (2016), another silk collage that tells the lot of every mother if not necessarily every woman. As Rachel Kelly writes in The Guardian last year: “One minute suited and blow-dried, at our desks; the next holding a clean-bottomed baby, surrounded by blond moppets in a perfectly tidy house. A perfect vision of juggling and having it all.” Here’s Zangewa then in skinny jeans, blue blouse and high heels, all set for a night out, her hands laden with multi-coloured toys. Those heels are open-toed and her bright crimson-painted toenails rhyme with her son’s pedal car. Again we find ourselves asking questions. Is this idealised state actually realisable? Is female perfectionism, the Champion Mum, an altogether healthy concept? Might mediocrity be ok?

Installation images by Rob Harris

And anyway – who are these women trying to impress? The rest of the family? The Inquisition (2007) has a line of people sat at a table looking out at us. Some are Black, some are white. What looks like granny (grannies in art and literature – they generally get a bad rap, rightly) stares out at us inquisitorially, judgmentally, from behind her school mam specs. She’s got her glass of wine so should be happy but you’re left thinking she’s disappointed in you. Again. It’s a family affair with all that implies, good and bad. Above their heads we read “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?”, a reference to Stanley Kramer’s 1967 movie about interracial marriage starring Sidney Poitier. Those of us who came of age in the 70s might be more reminded of the great Black Uhuru tune of the same name, with it lyric, “now that things and time have changed”.

Zangewa isn’t afraid of post-modern japery either. With The Dior Effect (2021) we see a male couturier darning a fold in a model’s white dress. We’re in the world of Paul Thomas Anderson’s movie Phantom Thread (2017) – the cult of the ‘genius’ who designs dresses. We remember the meaning of the phrase: the sensation that seamstresses have after hours with the needle, their hands working involuntarily after stopping the job, an outcome that one imagines is not entirely unknown to Zangewa herself after her time-consuming, labour-intensive efforts.

Lastly, three works with titles that pick up on pop culture. Sweet Dreams (2010) sees Zangewa languidly relaxing, reclining on the branch of a tree, one knee bent, a work reminiscent of Adrian Wiszniewski’s pastoral idylls. It’s a visual anxiolytic. Sweetest Devotion (2021) has two male figures, both wearing royal blue tops, a boy and a man, son and father perhaps. They sit on a striped cover giving Zangewa an excuse to demonstrate her considerable colourist chops with its rectangles that look like miniature Sean Scully paintings – a Scully on psilocybin that is. The senior figure looks quietly contemplative, content in his role as carer. The boy plays with his pad; the squiggles of his earpiece wires are another nod to Matissean cutouts. Finally there’s Back to Black (2015), a self-portrait that sees Zangewa pinching her LBD as she stands amidst the white tiles of a bathroom with its sink and plant pots. A purple towel jumps out at the eye. More questions. Has she dropped a stitch? Or like Amy, all alone, has she only said goodbye with words?

Margaret Atwood once said a sewing machine would relieve as much human suffering as a hundred lunatic asylums. One the basis of this slow burn of a show maybe she’s right.

Billie Zangewa, A Quiet Fire, is on at Brighton CCA until 13 May before touring to the John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, and Tramway, Glasgow