Installation view of Bad Manners, On the Creative Potentials of Modifying Other Artist’s Work, 2022. Photo: Damian Griffiths

Nobody knows quite what was going through the mind of Alexander Vasilyev when he decided to draw four stick-figure-circles for eyes onto two of the formerly faceless characters inhabiting Anna Leporskaya’s £700,000 painting Three Figures. It was his first day of work at the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Centre in Yekaterinburg. He worked shifts for a private security firm. The pen he used was a souvenir biro plucked from the gift shop of the museum. He would later claim that some teenagers, visiting the centre, had egged him on, and that he thought the painting was merely a “children’s drawing”, not a classic work by an important Suprematist artist worth millions of rubles. Having completed what Alexander Drozdov, executive director of the centre, referred to as his “smashing performance”, Vasilyev told his colleagues that he felt unwell before walking out of the museum and wandering off – presumably never to return. “He made a stupid mistake,” Drozdov said.

Ever since the infamous ‘Monkey Christ’ restored by eighty-one-year-old Spanish pensioner Cecilia Giménez at the Sanctuary of Mercy church in Borja in Zaragoza, the press and public alike have been fascinated by tales of great art mutilated by those tasked with its stewardship. It has become a whole genre of news item – and one charged with more than a hint of snobbery. The hapless defacers are inevitably presented as hay-brained rustics incapable of recognising the value of the masterpieces they have supposedly ruined. The reader of the story is granted the comforting fantasy of their own superiority, the reassuring knowledge that of course they would never commit such wanton philistinism (though I wonder what percentage of those who laughed smugly at the monkey christ of Borja or the freshly unblinded figures in Yekaterinburg had ever actually hear of Anna Leporskaya or Elías García Martínez, original painter of the Zaragoza fresco). At the same time, the stories serve a disciplinary function, reminding a mass audience increasingly solicited by visual art institutions of the proper attitude of restrained, hands-off deference in the presence of high-cultural monuments.

In his 1997 book The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism Since the French Revolution, Dario Gamboni notes the emergence of the word ‘vandalism’ in France, coincident with the arrival of Europe’s first major public collections in the early nineteenth century. He describes one particular “little-known engraving from the series of 1843 entitled Les Français sous la Révolution,” in which a ragged-trousered revolutionary is captured defacing a rather “demure” old sculpture. “The gross appearance and ‘primitive’ features of the sans-culottes stress not only his low extraction,” Gamboni writes, “but his underdeveloped nature (and, in the physiognomic tradition, perhaps his criminal nature too).”

But what if the vandal is not a working-class insurrectionist or a supposedly ignorant Russian security guard but a celebrated artist themselves, endowed with a cultural capital (almost) equal to the art works they are caught vandalising? How does the meaning of such iconoclasm change when we are allowed to presume the agency and intentionality of the iconoclast?

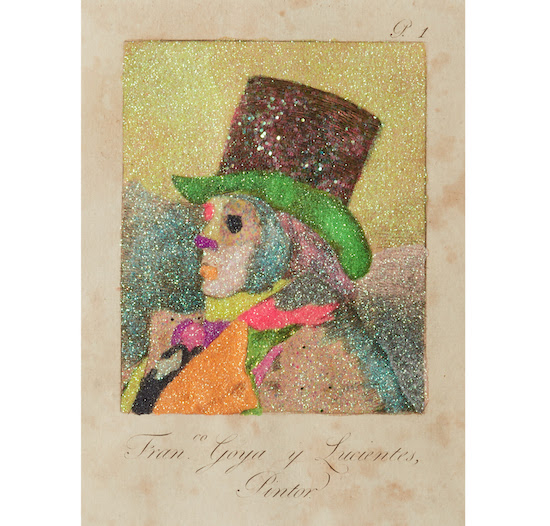

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Glitter Los Caprichos 01, 2019. One of 80 etchings by Francisco de Goya reworked and “improved” with glitter

A new exhibition called ‘Bad Manners’ at London’s Luxembourg & Co. gallery, co-curated with Jake Chapman, explores a variety of official – and not-so-official – collaborations, occasions when artists have sabotaged or slyly subverted the work of their peers and progenitors. It is a show about creators coming together – and falling apart. It is also a show about power, and about the creation – and occasionally destruction – of value in the global art world.

In 1987 Martin Kippenberger bought a 1972 Grau painting by Gerhard Richter, a monochrome grey canvas thick with visible brushstrokes, screwed four metal legs to its corners and turned it into a coffee table. Having bought the original at auction at Richter’s going market value, he then sold the work as his own under the title, Modell Inerconti. By all accounts he lost a significant wedge. In fact, as we walk round the exhibition immediately before the private view, gallery proprietor Alma Luxembourg suggests that you could probably still increase the value of the work simply by lopping off the table legs and hanging it on the nearest wall.

For Luxembourg, however, the “most bad manners” on display in the gallery are to be found in an Untitled by Jean Arp from 1947. A committed Dadaist and habitué of the Cabaret Voltaire, Arp had been incorporating fragments of torn paper in his canvasses for some time, but after the death of his wife, Sophie Taeuber-Arp in 1943, he ripped up and pasted into one of his muggy abstract paintings a drawing of hers – all criss-crossing lines and points, like a network of train tracks on an abstract territory. The work has been seen as an act of mourning or commemoration, an attempt to “carry on” his wife’s work after her death. It could also be regarded as an angry, even violent act. Significantly, it is the only example in the exhibition of a female artist’s work being vandalised.

But for Chapman such apparent acts of wreckage – as well as others in the show by the likes of Wade Guyton, Sherrie Levine, and Marcel Duchamp – far from being cruel or distasteful, represent the crucial break with the past that opens the very possibility of modernism in art. Think of Duchamp’s cheeky moustache of the face of the Mona Lisa, of Surrealism’s foregrounding of different kinds of witting and unwitting collaboration, the frame-bursting irreverence of Olympia’s gaze in Manet’s famous painting. In a sense, the avant-garde has always been iconoclastic through and through.

Bad Manners is full of artists coming together – and also breaking apart. We see Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring swapping a marker pen back-and-forth over their Untitled (1980) work with its block-capital legend: “OK SO WE DID SUPPRESS THEIR TAR ROOF TAR ROOF TAR ROOF”. We see Richard Prince and Cindy Sherman dressed in matching black suits and Beatle wigs for a double portrait from 1980, issued in an edition of ten colour prints – that then became two separate (but identical) editions of ten each when the couple split up. So it is fitting perhaps that Jake Chapman chose this moment to announce that he and his brother, Dinos, an artistic double act who together had been nominated for the Turner Prize and curated an edition of All Tomorrow’s Parties, had decided at the beginning of the pandemic to go their separate ways and work, from now on, as two distinct individuals. I guess that means they can now start vandalising each other’s work, instead of glitter-bombing old Goya prints.

Bad Manners is at Luxembourg & Co., London, until 15 May 2022