Two legs wearing cheap white leggings, their ceramic feet pedicured and dressed with metallic block heels, are growing out of a grey plinth displaying nothing. They greet you as you approach the exhibition space. They seem to be posing, playfully, doing nothing, maybe waiting?

It’s one of the sculptures by Claire van Lubeek in her solo show Baby Bar at 1.1 in Basel, her first in Switzerland, which draws from dystopian environments. Claire van Lubeek was born in Rotterdam, and is currently based in Geneva. In 2016, she started working on the Baby Bar, a project that is constantly growing with new pieces, and new configurations telling the story of a different moment in the narrative. In various discussions leading up to the show, she talks about the discrepancy of our expectations imposed on mothers and of the system we inhabit as a society.

The legs are those of the generator, the boss, who is doing nothing, surveilling their workers, imaginably smoking their cigarettes, drinking their beer, while popping out more babies from pustules grown on their skin. For as long as the babies live, they will work for the organism. They can sleep when they’re dead.Whether they do the former or the latter, the boss couldn’t care less, the construction and production will just continue on top of them, money won’t just come from being a fucking laze-tart!

While motherhood must be one of the most sacred and rewarding tasks one can be blessed with, it is also endless unpaid emotional labor performed while simultaneously under the pressure of the whole world’s hopes for its future generations: Childhood as a capsule, shielded from the bigger organism and the mother to all citizens, a system where all participants are either oppressor or oppressed in one way or another.

The theme of motherhood and pretence of caring for others in exchange of a personal economic advantage is a recurring theme in van Lubeek’s work. In 2015, in her collaborative performance Excellent Two Lands; The Two Ladies/ The Mother Dance Of Survival with Linda Voorwinde and K.I Beyonce, chickens are the subject: Van Lubeek and Voorwinde, dressed in bathing suits and sunglasses, keep chickens in baby carriers on their chests, functioning as their sole caretakers at Lodos gallery in Mexico City, while sunbathing together, an activity chickens engage in just as naturally as humans do.What seems like a sacred interspecies bonding session is broken by the boiling of the chickens’ potential future dependants, their eggs.

By interweaving these roles of these compared systems of what is supposed to be benevolent, nurturing care also in Baby Bar, van Lubeek creates an apocalyptic narrative, in which the bar is the last remaining place on earth. There, the non-gendered oligarch can carry and birth babies to be at their own disposal as working force, and generator of capital.

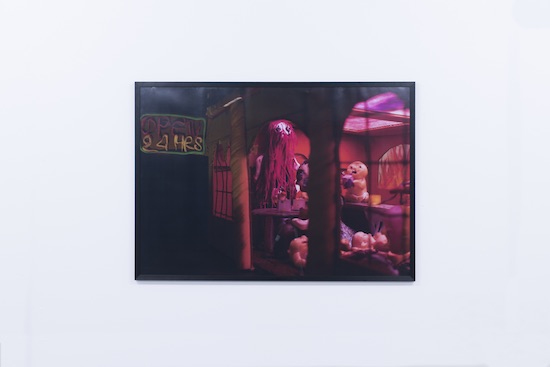

Claire van Lubeek, ‘Club Hysteria’ (2016). Detail view 5. Photo by James Bantone. Courtesy of the artist and 1.1, Basel

Glazed ceramic feet and a hand clutching on to their bag manifest this oppressor. Macro photographs taken inside of a shoe box polymer clay Baby Bar frame the show. They display scenes of this twisted system in contrastingly warm and cozy red tones. It reminds of an uncanny dollhouse, but the acteur is not evident, the babies seem possessed, worn out, while a sign heralds the round the clock opening times of this dystopian bar.

Six baby heads with long, bright, blue, wavy hair have been joined together to form The Fountain. It lays on the floor, somewhat sad, somewhat poetic. The babies’ heads seem to be in discomfort, but the generator doesn’t care. The breast milk has to flow, it’s their only job, how about man-ing up? They belong to their bearer, and their bearer wants to keep the customers happy, and customers want to drink the sweet juice of youth.

The sources feeding into van Lubeek’s work stem from examples spanning through past decades, but they just as well speak for our present and our future. Oppressive communities of all scales, our mistreatment of our natural environment, or what is left of it, and the disregard of human rights and adequate working conditions aren’t phenomena attached to a specific time, but are repetitive and continuous in their nature, which is to say, in human nature.

Claire van Lubeek, ‘Baby Bar #2’ (2017, shot by IC Studio). Installation view. Photo by James Bantone. Courtesy of the artist and 1.1, Basel

On the second plinth, there it hails, a ceramic work entitled Club Hysteria. It testifies to this negligence and fully conscious rejection of responsibility. Babies bodies are crushed under new layers of construction, becoming one with the infrastructure that carries atop of it: A bar. A bar where the customers, the sort of individuals who would survive and still strive after an apocalypse caused by accepting and supporting a separatist system to its extremes, are welcome. Please, they should just come in, have a beer and calm down from their stressful day of supervision. Everyone needs a safe space. This is theirs. The customers love it so much, the tiny workers can’t even keep up with cleaning the place! It’s secondary though, the main thing is keeping the customers happy, and keeping the money flow steadily rising.

Van Lubeek manages to balance the fragility of the pieces with their stories of such shattering truths that we can relate to on individual levels, and to provoke a cocktail of ambivalent emotions within us. Motherly instincts and empathy are met with feelings of shock, unease if not desperation, maybe revolt, maybe all the same with recognition of ourselves in the boss as well as the babies.

Clare Van Lubeek, Baby Bar, is at project space 1.1, Basel, until 7 October 2017