"Hi Dan, I’m an artist and I’ve painted my credit card and it’s currently being exhibited in the window of War Gallery in London. I think it makes sense if Barclaycard buys this painting from me. It’s currently on eBay with many people watching the auction. It would be a shrewd investment on your part and at the same time you will get the money back as I will pay it back onto the card. All the best Babak."

"Hi Babak, I’ll pass this on for you. Is the card number in the painting your actual Barclaycard number?"

Some major financial institutions, like Deutsche Bank and Bank of America, have whole art departments, swathes of liveried curators and indentured experts, to manage their art world acquisitions. The likes of Gerhard Richter will see the red carpet extended to them at JPMorgan, their works the very jewel in a collection going back decades, heavy with Picassos, Rauschenbergs, and Warhols. But when Babak Ganjei tried to sell his painting of a credit card, All the Power to Barclaycard, he didn’t get through to the corporate art department. He got Dan in Customer Services. And then Dan mysteriously turned into Dean.

"Hi Babak, I’d recommend we block this card for security reasons, do you want me to block this for you? Thanks, Dean."

"Hi Dean, I’m worried that would compromise the integrity of the piece. I don’t know. What do you think? All the best, Babak."

“I think as a proposal, it makes sense,” Ganjei says to me, when we meet up at the War Gallery, where his solo show, It’s Really Not Funny (including the painting of his credit card) is currently on display. “I’ve racked up this bill doing this –“ he gestures around the room, to the mass of canvases filling every available space on the walls “– it’s an investment for them. And what I’m gonna do is put it back on [the card] anyway. So it would really help me, anyway.”

Ganjei was born in London, but moved to Bournemouth at the age of eleven (“It was pretty white,” he says now of the southern seaside resort. “It was a bit like suddenly being the only ethnics in the town.”) Coming from an artistic family – his father, an architect, and his mother, a painter of “landscapes and flowers” – he started drawing young. “I always drew,” he recalls. So after passing his A-levels, Ganjei made his way to Central St. Martin’s in 1997, the very height of London’s mid-90s art fever.

Much of the rest of Ganjei’s biography can be reconstructed from the oil-painted CV on the wall of the War Gallery. “1997 Sensation” it begins.

Did you have work in the Royal Academy’s Sensation show, then? Alongside Damien Hirst’s pickled shark and Marc Quin’s self-portrait made of his own blood?

“No,” he admits. “That would’ve been cool – I would’ve been only 17. That was sort of when art started for me, when I got into that. But I’m happy for people to misunderstand that and go with it. I should probably just go with it.”

“2001 Graduate BA Fine Hons CSM” the painted CV continues, “2001–4 Work from home. Wait to be discovered. 2005–11 Join bands to be broke in a gang…” A few lines later, the resumé ends desultorily “2009 Alcohol. 2017 Run out of canvas” This last line hangs ironically over several feet of empty space on the canvas.

But like all autobiography, Ganjei’s CV has an air of fiction about it. Sure, it is “pretty much”, as he tells me, his real CV. Yet still it contributes to the creation, across all the works at War, of a particular tragi-comic character, developed across distinct chapters, telling different stories.

The words “You’ve got your story,” typed into an eBay customer message box was how one of the more public chapters in Ganjei’s recent history came to an end. It began almost four years ago, in the early spring of 2014. “A lot of things happen by accident and then you see where you can take it,” he says now of the strange turn of events that saw him ending up in the pages of the Express, The Independent, and The Metro, fielding calls from Five Live. “Because I live in De Beauvoir and it’s quite expensive. But I live there almost by accident, paying off a friend’s mortgage, so it’s really cheap. And then the funny thing is it’s almost like you’re sort of stuck in De Beauvoir, because it’s cheaper to stay there than go anywhere else.”

“But I was sort of getting priced out,” he continues, “and I’d bought quite an expensive sandwich that wasn’t very good. So all I was trying to do was sort of something to get the money back from that.”

Annoyed by his over-priced lunch, he gathered some “decent looking twigs” from the floor of De Beauvoir Square in East London and put them on eBay with a starting price of 99p. “and I did the write up and I measured them. Did everything properly. I dunno. I think a friend bid on them as a joke and somehow they got up to nine pounds.”

Nine pounds, Ganjei reflects now, was “just the right amount” for his twigs to start to gain attention and gather momentum on a slow news day in March. “Set of twigs go on sale on eBay. Don’t all rush at once” read the Metro’s headline. Despite the article’s derisory tone, people did indeed rush. The bids went up. And up.

“The interesting thing,” Ganjei reflects, “was I’d picked them up and put them in my living room. So they were sort of just sitting there. And then that afternoon, they’d suddenly gone up to nine pounds. Then I went to a gig and came back and the next morning suddenly they were like thirty-five pounds. Then I was, like, I should probably move them. They were just twigs, but now they’re thirty-five quid…”

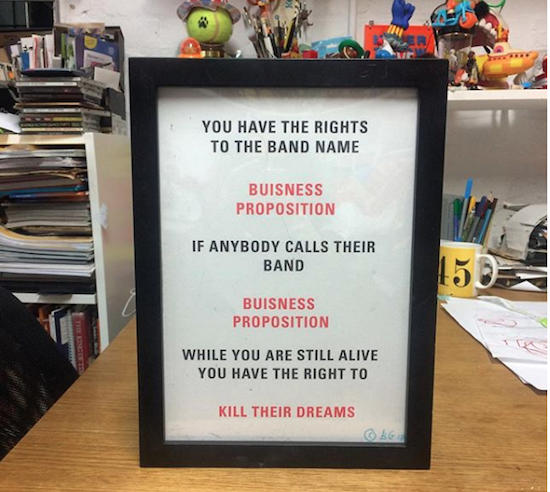

The peculiar nature of value – what Karl Marx once called “the mystical character of commodities … the fantastic form of a relation between things” that makes ordinary, mundane physical things into a kind of “social hieroglyphic” – is the issue at the very nub of Ganjei’s work. How does a “decent looking” but essentially useless bundle of twigs end up going for £67 on eBay? Or, to cite some of Ganjei’s other auctions, a “forged Beyonce signature” or a printed contract offering intellectual property of the misspelt band name “Buisness Proposition” or a “half-full glass of water”? And, likewise, how does a little plastic oblong become the very image of currency and exchange – a credit card?

Of course, such questions have a long lineage in the history of twentieth century art. Marcel Duchamp’s elevation of a urinal stall into a “readymade” artwork. Yves Klein selling “voids” of empty space. Piero Manzoni’s tinned shit. The half-filled glass of water, in particular, references Michael Craig-Martin’s classic 1973 work of conceptual art, An Oak Tree. But as Ganjei rightly points out, “Michael Craig-Martin did that, obviously, in a gallery – but no-one has tried to shift it on eBay. It’s context, isn’t it?” And context is everything.

As everyone in the music industry already knows (and Ganjei, as we can see from his painted CV, spent six years playing in the Mephis Industries band Absentee), the nature of online exchange transforms questions of value fundamentally. An album of recorded music can pass insensibly from being worth fifteen pounds in 1996, to being more or less worthless just a couple of years later. And a bundle of twigs, useless and valueless to a man, can rack up £67’s worth of auction bids in a week or so.

“But the person that bought them,” Ganjei says, “didn’t pay for them. They basically just emailed me straightaway and said, you’ve got your story. I even paid the commission on it in the end. So I lost eight quid.”

The twigs, then, are now defiantly back on sale.

“I think I’ve always been trying to get to the point of almost trying to take all the art away,” he says. “I remember when I was art school, thinking, I just want to be walking around Sainsbury’s and that’s it. That’s the work. So I spend my whole time trying almost to take the value away from it, while still believing in it.”

Somewhere in the interstices between the erasure of art and the erasure of value, arises the very possibility of meaning and desire in the twenty-first century, when art is caught steering precariously through the Scylla of Buzzfeed listicles and the Charybdis of corporate art collections.

“I’ve got friends who work in interiors,” Ganjei says, “and they buy pieces for show homes and things for thousands of pounds. What they want in those places is something that says absolutely nothing. It’s just a status thing. Nobody wants meaningful. Not on their walls.”

Hence, an oil painting of a credit card, because, as Ganjei says, “That’s the only place art sells, right? Banks.”

It’s a loving portrait of their child, I suggest.

“Exactly! Why wouldn’t they want that?”

Babak Ganjei, It’s Really Not Funny, is at War Gallery, London, until 14 February. His current eBay auctions end in one day