Now in its 8th year Arrow Factory is one of the longest running alternative spaces in Beijing, proving that despite the dominance of the commercial artworld and an unpredictable relationship with authority, there are sustainable ways to act creatively within the everyday life of this city.

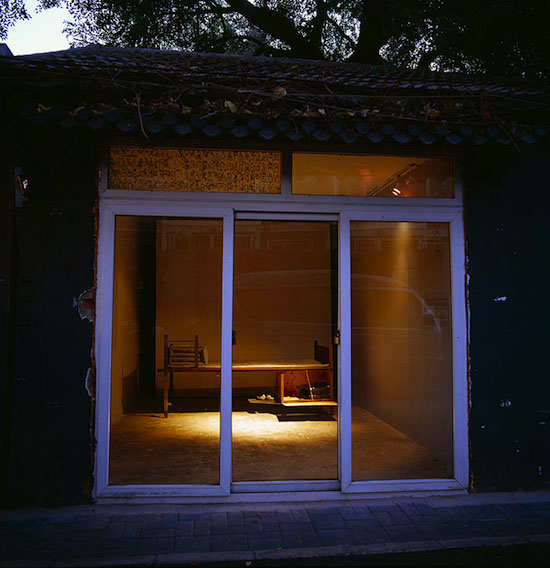

Launched in 2008 by the artists Rania Ho, Wang Wei, Wei Weng, and curator and writer Pauline J. Yao, Arrow Factory’s tiny store-front space is situated in an area of hutong – the narrow alleys that are a traditional feature of Beijing. Hutong are now sites of rapid gentrification and Arrow Factory sits amongst a changing scenery of old-style family-run food stores, fashion boutiques, and craft breweries, while the residential spaces behind vary from near-slum conditions to more recent luxury makeovers. Although Arrow Factory is a closed space, the projects viewable behind their glass doors often respond to the location, maintaining a low-key presence on the street.

I met up with Rania Ho and Wang Wei on one of Beijing’s beautiful winter afternoons in Wujin, their café and bookshop a few doors down from the Arrow Factory space.

Why did you start Arrow Factory? Where did the idea come from?

Rania Ho: Our interest is in alternative practices, working outside of galleries, in public spaces, and exploring the undefined grey areas. This kind of practice has an extensive history in Beijing. We were already engaged in this kind of practice so creating Arrow Factory was a natural extension of that working method. We started the space at the height of the Chinese art market. The market started taking off around 2006 or 2007.

Wang Wei: There were lots of massive new galleries, spaces, and art museums at the time, and we felt that they were not that interesting for us.

RH: We wanted to find alternative ways of working. The art world was very commercial at that point and most people believed that this was “the only way it would work!” Many things that were originally underground suddenly became commercial, and very marketable. There was an over emphasis on market value as a criteria for making artwork. Our objective in starting this space was to give our artist friends alternatives ways of working, offer other modes of thinking about the creative process and explore additional options for exhibiting.

WW: We’re artists, but Arrow Factory was also established with Pauline, a professional curator. It’s quite a different experience for us to work together with her. It has the feeling of being more long-term – something real, not temporary!

RH: Of course even with Pauline I don’t think we ever thought about this as a long-term project. Our initial impetus was that we thought it could be a fun and temporary project – definitely part of a “let’s see what happens!” mind-set. The space and all our shows are conceived in this spirit.

WW: In the beginning we decided to make the space small and flexible. Doing this presents certain challenges; sometimes constraints make the work better.

RH: The space asks artists to be very focused. It’s a flexible raw space, very mutable. It’s not a pristine box; it’s very rough, very raw. The work is right there on the street, without a big heavy door to push through as other art spaces might. It’s a big glass window that allows any passer-by to see straight through to the artwork, it’s completely open. Essentially public art.

Hu Xiangqian, A Looks Like B

I know you live just close by, but why did you choose this particular space?

RH: We were looking for something small, in the centre of the city that didn’t require a pilgrimage to visit (as the galleries in the art districts can be). It just so happened that this space became available. After Chinese New Year there is usually a lot of turnover in commercial property. The guy who was running the vegetable stand here didn’t return, so we rented it. Before we found this space, we also considered renting a shop window only, so that another business could continue their trade inside and we would use the window display. Not sure if that would work, but it was one of the ideas that was floated. We actually intended to rent a much smaller space!

So your first show was a show of your own work.

RH: It was Wei Weng and I. We thought the most responsible way to test the waters was to do our own show first and then see what happens. We were slightly wary as to what the reaction would be.

Why?

RH: Up until the early 2000s there had been many instances of authorities shutting down exhibitions. Of course by 2008 the art market was very hot and there was far less government intervention in exhibitions than in the past. It was unclear how the local authorities might react, and we were unsure about how our neighbours might respond.

WW: Based on our experiences in the late 1990s, exhibitions got cancelled ostensibly because the space had no license. Of course we don’t have that kind of license here. We were unclear what would happen, so we just started the space, and then waited to see what would happen. But actually it’s been fine.

RH: Arrow Factory is totally non-commercial. We do not buy or sell any artwork. We intentionally don’t have a collection of any sort. We’re not really interested in the commercial side of art all of art at all.

And you don’t do big events, or openings even.

RH: The whole point was to try to keep the overhead as low as possible, and really focus on the artworks. It’s understood that nobody is paid to organise Arrow Factory, all the funds that are donated – and we run completely on donations by foundations and individuals – goes towards either paying the rent, or covering production costs for new projects.

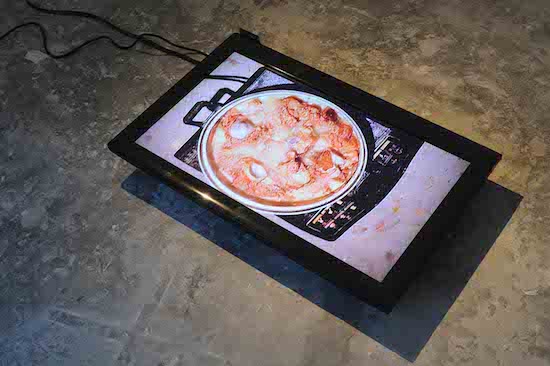

Li Yueyang, Time Spent

What kind of things have artists been able to do?

RH: For example Hu Xiangqian, a performance artist, made a set of video works that were not performative and didn’t even have images of himself in them, which is certainly not the way that he would normally work. There have been collaborations that probably would not have happened under normal circumstances. Yeh Wei-Li, a Taiwanese artist, and Li Mo + Kong, two Beijing-based architects, created an installation that dealt with cross-strait relations between Mainland China and Taiwan. There was also Li Yueyang, an ex-con, who replicated his prison bed down to the millimetre based on the physical sense-memory of sitting and sleeping on it. He included a uniform, pair of shoes and a prisoner’s handbook, all smuggled out of the corrections facility for this exhibition. Artist Shi Qing made road-blocks out of wood painted with colourful patterns which he then dismantled and left in the alley for people to re-use. That piece took advantage of the interesting dynamic of public space here in the hutongs. Although the hutong often looks like public space, there is a process where the public gets co-opted by the private, with certain unspoken rules, so his project was testing those invisible barriers.

Have you worked directly with the neighbours at all?

WW: Not that directly. A few projects may have a little bit of collaboration. Ni Haifeng’s project ‘Viva La Difference’ worked with nearby tailor to reproduce a “high-end” fashion garment using offcuts of fabric. In 2009 we did a group show called Just Around the Corner, in which we made and installed different works in various spaces around the hutong.

RH: As part of Just Around the Corner the artist Hong Hao gave the vegetable sellers a weight scale and piles of unwanted art catalogues that he and his friends had received at exhibition openings. The vegetable sellers were instructed to give to each customer the equivalent weight in books as the vegetables they were purchasing. That was very popular!

At the moment you have an installation of the work of photographer Xyza Cruz Bacani.

RH: Yes, she’s a Filipina photographer who spent 10 years working in Hong Kong as a domestic helper. In her spare time, and with the encouragement of her employer, she learned and practiced photography.

WW: We saw her work at the Parasite Gallery in Hong Kong and I thought it would be interesting to show her photographs here because maybe they have some relationship with the hutong context.

RH: She wasn’t able to come to Beijing to install as she’s very busy right now, and it turns out it’s a little bit complicated for Filipino Passport holders to get Chinese Visas.

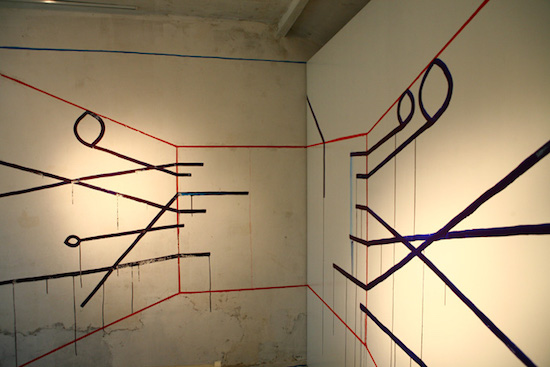

Wei Wang, As Prospects Get out of Range

Have your interactions with local people been pretty positive, given the changing populations in this area?

RH: At least for our neighbours, Arrow Factory is a point of interest as they go on their evening strolls. They are certainly curious as to what goes on here. For us, that moment of acknowledgement, the moment of the neighbours looking and seeing is enough. It’s a small gesture that perhaps can get us someplace where we can talk about tolerance, about openness, about sparking some different ideas. Arrow Factory is just a small presence; a slow burn rather than a dramatic act.

Like Shi Qing’s wood. I remember for a number of years afterwards you would come across them being used in other random parts of the hutong.

RH: And if you’d seen the original pile of logs, then the sight of them would spark a memory: “Oh yeah, there is that thing! It’s still around!”

What do you think the environment is like for alternative spaces now in Beijing?

RH: It’s very good! Fantastic that there are so many small spaces around, and that everybody is doing their own thing. It’s what we had all hoped for from the beginning. At the time we started Arrow Factory everybody was telling us that it was impossible to do a not-for-profit, non-commercial space in Beijing. But we wanted to try; we wanted it to be possible! And now, eight years later we have shown that it can work, but some sacrifices have to be made. It’s amazing that since then many people have taken up the mantle of independent art spaces. Everyone has their own way of doing things, their own networks, and tastes. Diversity is good. The more the better!

Xiao Fang, an exhibition of work by Hu Yinping, is at the Arrow Factory, Beijing, until 20 February